![]()

Chapter 1

Finding the conceptual center

MODELS AND FRAMEWORKS

BUILD-TO-THINK PROTOTYPES

LISTS AND OPEN-ENDED WRITING

OBJECTIVES AT THIS STAGE:

Externalize thinking.

Achieve clarity around what’s known, what’s desired, and what’s proposed.

Build alignment and shared meaning among team members.

We have a condition, when creating The New, of needing to process the mess of inputs we have gathered. We have quantitative data, qualitative data, industry reports, trend reports, rumors, stories, our own experiences. We’ve read it all. We may have lived it through direct experience with users and their lives. Now we must make sense of the soup. And we must make meaning from it. How do we decide which of all the things we have lived, read, and seen really matter most to the challenge at hand?

HOW TO “KNOW WHAT YOU KNOW”

Neuroscientists tell us 95 percent of brain activity is unconscious. For the sake of argument, let’s say most of that activity is not worth conscious thought—digestion, walking, and cell division likely work better without our input. But while our brain’s ability to operate and store information unconsciously makes us efficient, it may also be a problem: What if we need some of that 95 percent? What if some of what we have sublimated is important to the challenge at hand? An important first step in creating The New is finding a way to surface and organize the massive number of inputs our brains have so efficiently and automatically stored. We need to make it all top of mind again.

This is where communicating The New starts: surfacing what is known and then finding and articulating the conceptual center of the work. No effective communication can take place if we don’t know what we are trying to say. No effective progress can take place if a team does not have a shared conceptual model of what’s important. Articulating what we mean, whether on our own or as part of team, is a critical stage in communicating The New.

The challenge of “unspeakable data”

In creating The New, we face an early-stage condition of unspeakable data—the data of our senses, thoughts, and emotions. This is author Peter Turchi’s phrase for capturing the fiction writer’s condition in his book Maps of the Imagination: The Writer as Cartographer. In the context of creating The New, “unspeakable data” refers to all the rich details and information we have ingested as we framed our challenge, conducted research, and began to explore directions. Much of that experience now lives in a subconscious state that some might understand as intuition. We know our bodies take in information through our five senses at a speed and depth that we are largely unaware of, but that we are richly wired to interpret and apply with little conscious thought. This may explain why so many designers and innovators rely on field research methods to better understand the reality of their customers: Research teams go into customers’ homes and workplaces and cars and coffee shops so that they may observe with their eyes and with their hands, noses, and ears the everyday context and activities of the people they are creating for. In these cases, our bodies are our field instruments as much as our field notebooks. This data becomes “unspeakable” because it is often deeply embedded in our sense memory, and it may or may not ever make it to the pages of our field notebooks. We know it, but we may not know we know it.

How to surface unspeakable data? Or unspoken knowing? What are effective processes for working through the mess and finding that conceptual center? In this section, we look to the fields of design, engineering, education, and journalism to identify methods for early-stage synthesis. And we go back to basics to include those often ignored ways of knowing that are part and parcel of our conceptual system. On the basis of my research, I cluster these methods into three basic categories:

- MODELS AND FRAMEWORKS

- BUILD-TO-THINK PROTOTYPES

- LISTS AND OPEN-ENDED WRITING

The ROI and PFP (Pain for Progress) of these approaches

Although helping individuals and teams align on what they know is a critical milestone, it’s actually not that hard to do. Years of professional practice and teaching tell me this: For all the confusion and mess, people in the early stages of projects know more than they give themselves credit for. We are, after all, sense-making machines driven toward answers. But self-doubt, piles of facts, and a fair bit of ambiguity can impair a team’s vision and clarity in ways that are uncomfortable and time-consuming. Too often, getting to conceptual clarity is where the team collides with the uncompromising requirements imposed by the project’s Gantt chart.

If thirty minutes of open-ended writing (one of my favorite accelerants) or two hours of rough prototyping could save a team days of unfocused meetings and group gropes, would that merit stepping out of the Gantt chart? In the pages that follow, I propose no method or approach that I have not used myself. These require no specialized knowledge, equipment, or software. They work on the train ride in, or at the lunch table. They work for individuals and for teams.

What they require is a willingness to ask an open-ended question, “What do we know?” and to proceed from there as if the answer is within reach. Because it is.

MODELS AND FRAMEWORKS:

Thinking with our eyes

All models are wrong, but some are useful.

— George P. Box, statistician and author of Empirical Model-Building and Response Surfaces

WHAT CAN MODELS DO FOR US?

Models or frameworks are abstract, diagrammatic representations of information or observations. Models represent a particular view of reality, and so can be partial and subject to change, and may even represent incorrect interpretations. What makes models useful is their ability to abstract and simplify complex content.

Models are particularly useful in the early stages of creating The New, when a team may find itself awash in data and in search of meaning. Models are effective at this stage because they remove distracting detail and anecdotal content to reveal an underlying structure or pattern in the information. Models install boundaries on the system of ideas, telling us where the conceptual space begins and ends. All this de-cluttering and distillation fosters clarity. It builds consensus (or at least supports conversations that can lead to consensus) and opens up questions about what could exist in the future. This may explain why so many practitioners who favor models say that the process of making models may be more useful than the model itself: Model creation requires reflection, editing, negotiation, and storytelling. These are all excellent activities for individuals or teams in search of synthesis and convergence.

Because they are visual expressions of thought, models do something that text cannot: To borrow a phrase from quantitative visualization guru Stephen Few, models allow us to “think with our eyes.” Our eye/brain hardware has optimized over thousands of years to process the visual world for patterns and meaning, and we can do so in a fraction of the time it takes to read and translate that meaning from text. This intelligence is not only faster, it’s higher bandwidth: We can process much more visual data simultaneously than we can textual data, which demands a linear process. Thinking with our eyes provides a different channel into a conceptual space: one that is highly complementary to verbal methods, such as writing or talking, but uniquely able to compress a sprawling problem into a compact space and to support conceptual play with its parts and pieces. Using a model, a team can see the whole conceptual space at once, and then dive into a specific portion of the space without losing sight of the whole.

Let’s look at three examples of how models can help teams find the conceptual center:

- MODELS FOR MANAGING COMPLEXITY

- MODELS FOR BUILDING A SHARED BASIS OF JUDGMENT

- MODELS FOR CREATING ALIGNMENT

MODELS FOR MANAGING COMPLEXITY

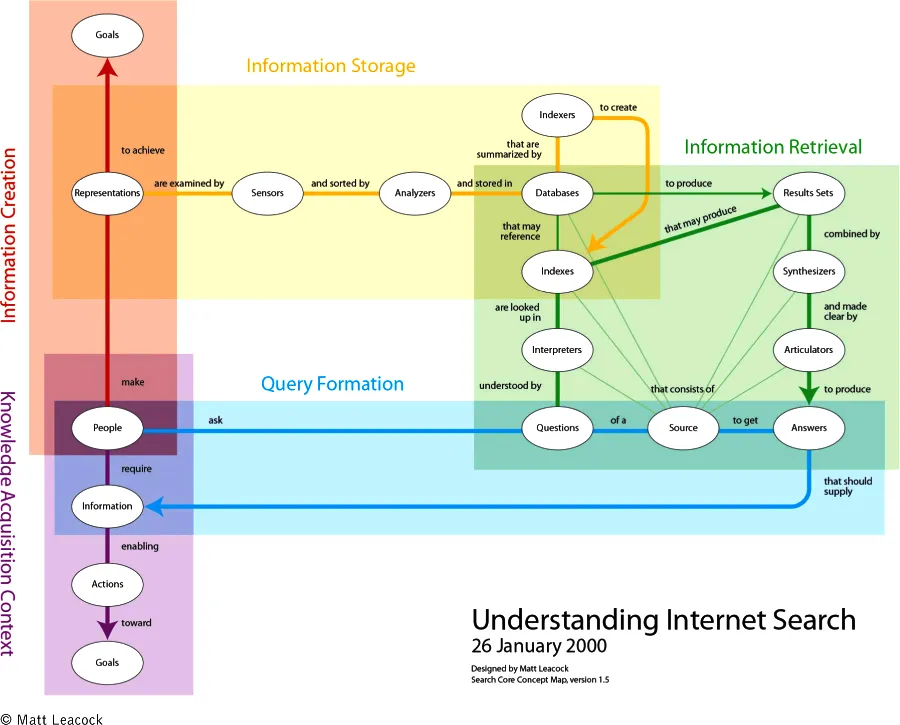

How does Internet search work, anyway?

In 1999, it was still the Dark Ages of Internet search. Industry leader Netscape had just acquired a small startup with an expertise in search.

Netscape was still in the process of folding this new capability into its search services when the VP of products approached design lead Hugh Dubberly, and asked him to manage a redesign of the search interface. Hugh assigned promising young designer Matt Leacock to the team, a group composed of “fairly aggressive, opinionated engineers,” in Matt’s words. The first meeting didn’t go well. “He’d been basically almost kicked out,” says Hugh, “they didn’t know why he was there.”

To state the obvious, Internet search was an amorphous and complex topic to someone outside the field. Hugh handed Matt a vintage copy of Gowin and Novak’s Learning How to Learn, which outlines in detail how to create concept maps as a tool for managing unfamiliar, complex subjects. Matt followed the protocol: He interviewed the engineers, project leader, and an external subject expert or two. He drafted his model, which Hugh reviewed and liked, and went into the next meeting to present it.

“He comes back after the meeting, and he’s kind of all hangdog,” as Hugh tells it. “I asked him what happened, as I thought the map was fine and that everyone had bought into it. He said, ‘Yeah, you wouldn’t believe it, though, a fight broke out.’ Matt’s map had brought to the surface the fact that the mental models among various engineers for what was happening were not consistent.” As Matt recalls, “There was a lot of contention around how to differentiate the search engine and where to drive user interaction with the product—the search page or the directory.” Through the model, the team had discovered something very important—they w...