![]()

1

Information Retrieval in Digital Environments: Debate and Scientific Directions

1.1. Information retrieval, current and future challenges

Information retrieval is a central and essential activity. It is indeed difficult to find a human activity that does not need to retrieve information in an often increasingly digital environment: moving and navigating, learning, having fun, communicating, informing, making a decision, etc. Most human activities are intimately linked with our ability to search quickly and effectively for relevant information, the stakes are sometimes extremely important: passing an exam, voting, finding a job, remaining autonomous, being socially connected, developing a critical spirit or simply surviving.

From the psychological point of view, the activity of information retrieval presents several characteristics that make them both unique, complex and fascinating [DIN 12a]:

– Information retrieval in digital environments is a necessity in a growing number of human activities. Daily, we must search for information (an address, a phone number, a time slot, a name, etc.) in various digital environments of constant evolution (GPS, mobile phone, Website, electronic terminal, etc.).

– Information retrieval is a composite activity, which typically requires reading, memorizing, writing, taking decisions, etc., these activities being cognitively complex and corresponding to areas of scientific research on their own.

– Information retrieval is a dynamic activity in the sense that the environment in which the activity is carried out evolves independently of the actions of the user (the same query in a search engine on the Web gives different results in an interval of a few seconds).

– Information retrieval is an iterative process, since the behavior and knowledge of the user are constantly changing at the pace of the information returned by the information system.

In 1998, the first Google index had 26 million Web pages. In 2008, Googles engineers counted a trillion Web pages (or a thousand billion). Since then, the number of pages has no longer been counted, and only the number of Internet sites is recognized. In June 2011, there were 346,004,403 Internet sites (source: Netcraft.com).

It is virtually impossible to know with accuracy the number of Internet sites and/or Web pages (sites protected by password, military sites, invisible Web, etc.). However, this is no matter, the only important data are the incredible progression of this mass of information, which everyone can easily access today. But, more than the mass of information, it is especially the relationship between humans and information, that has significantly evolved and is still evolving.

1.2. What are we talking about?

The term “information retrieval” (“recherche d’information” in French) includes both the scientific field and the related human activity. Some professional French-speaking organizations, such as the French association of information and documentation professionals (ADBS 2004) or even the AFNOR (French national organization for standardization 1993), proposed distinguishing information retrieval from information research:

– Information retrieval (recherche d’information in French) is the “totality of methods, procedures and techniques that allows, based on search criteria specific to the user, the selection of information in one or more repository of documents more or less structured” [AFN 93].

– Information research (recherche d’information in French) is the “totality of methods, procedures and techniques that aim at retrieving the relevant information from a document or a set of documents” [AFN 93].

The difference remains subtle and above all too superficial regarding the place of the end user in the activity. Because the English lexicon concerning the areas of computing and new technologies is more extended and more precise, it is logical to find more words (and therefore more accuracy) on topics related to these areas, such as information retrieval. In the English language, several specific terms coexist for mentioning the scientific fields related to information retrieval:

– Information retrieval: generally noted “IR”, these terms refer to the scientific field concerned with everything that falls under the search for documents or information, research in documents and whatever environments are considered (physical environment, off-line digital environment, such as CD-Roms, digital library, Internet, etc.). IR is a multidisciplinary field primarily involving disciplines such as computer science, mathematics, information science and communication, psychology or even economics. Initially, one of the first objectives of researchers in the field of IR was the creation and development of technical systems and interfaces allowing quick access to relevant information in the increasingly large and more dynamic informational bodies.

– Information behavior: this refers to all of the human behavior related to all sources and channels of information (television, telephone, paper documents, Internet, face-to-face communication, etc.). In this case, human behaviors are not necessarily motivated by a need for information. For example, studies interested in the impact of exposure to advertisements (i.e. the “passive” consumption of information) are part of this scientific sub-domain.

– Information-seeking behavior: this refers to all of the human behaviors explicitly oriented toward obtaining information, regardless of the media (e.g. textbooks paper, magazines and Websites). In this case, a need for information is, therefore, at the basis of the studied behaviors, whether this need is conscious or not.

– Information-searching behavior: this refers to human behavior directly concerned with information retrieval, from a sensorimotor point of view (e.g. using the mouse or the keyboard) or intellectual (e.g. evaluation of the relevance of information).

– Information use behavior: this corresponds to human behavior involved in the processing and the assimilation of information found to knowledge already stored in memory. Here again, the sensorimotor aspects are sometimes studied (e.g. note-taking and annotation of texts) as well as the psychological aspects (e.g. memorization of information found).

If it is difficult to define with precision the exact shape of the different sub-areas related to IR, the task becomes even more difficult in the case of human–machine interactions (HMIs).

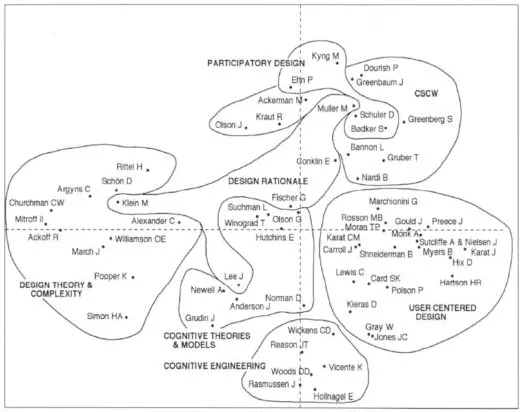

In order to define the different scientific sub-fields related to HMI, Wania, Atwood and McCain [WAN 06] have investigated the “genealogy” of different productions (articles and conferences proceedings). More specifically, these authors have studied the citations and co-citations in various publications based on the 64 authors most frequently quoted in HMI. After a review of bibliographic databases for the Institute of Information Science (ISI), Wania, Atwood and McCain [WAN 06] were able to identify the relationships existing between the articles; these relations take the form of citations and co-citations of the authors of reference. In addition, seven distinct groups could be identified in the studies conducted on HMI (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Affiliations between the articles in HMI, according to [WAN 06]

The two axes along which the seven sub-areas of HMI are divided and have been translated by [WAN 06] in the following manner:

– The horizontal axis distinguishes the studies according to the main center of interest, from technical systems to the human individual.

– The vertical axis distinguishes the studies according to the degree of involvement of end users in the design and/or evaluation process. For example, the work of Jacob Nielsen is located at the right end of the horizontal axis indicating clearly that the end user is the main factor of interest; however, since his work rarely results in experiments or empirical studies, this author is located in the lower half due to the involvement of individuals in his research.

This classification of studies in HMI according to these two axes allows us to address differently the conceptual and methodological frameworks in HMI. In fact, generally, research about HMI is presented by distinguishing works at the design level (i.e. conception) from works at the assessment level. However, it is difficult to distinguish studies according to this dichotomy, since most of the studies address the two dimensions (to various degrees of course).

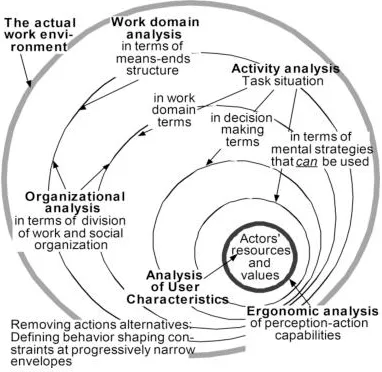

Thus, not only does information retrieval cover a multitude of studies, sometimes very different, but works on HMI also cover a plurality of disparate studies. It is appropriate to add a third difficulty in the apprehension of scientific studies interested in human behavior in information retrieval in digital environments: the level of granularity chosen by the researcher. According to Fidel et al., [FID 04], the “size of the magnifying glass” used by the ergonomist researcher or practitioner determines its theoretical and methodological choice. And this “size of magnifying glass” is itself determined by the questions underlying the research or the intervention (Figure 1.2): Impact of organizational factors? Strategies of visual exploration? Task analysis? etc.

Figure 1.2. The concentric approach of Fidel et al. [FID 04]

1.3. Interaction and navigation at the heart of information retrieval

As we will see in detail in the following chapters, the individual has been quickly (re)placed at the center of interests of scientific studies focusing on the activity of information retrieval (for a summary, see: [DIN 12]).

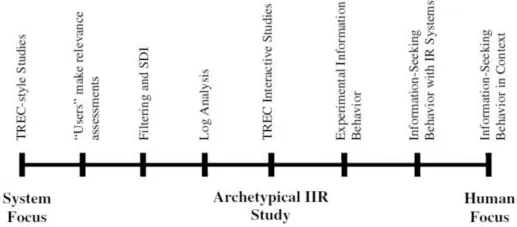

According to Kelly [KEL 07], most of these studies can be located on a continuum (Figure 1.3). At one end of this continuum, studies are mainly focused on systems and technical devices related to information retrieval; at the other end of this axis are found studies mainly focused on behaviors and human factors. According to the approach considered, the theoretical frameworks and methodologies used differ.

Figure 1.3. Scientific research on information retrieval according to the continuum proposed by Kelly [KEL 07]

The significance of Kellys design [KEL 07] is to consider that the balance and/or break between these two extremes is the interaction: indeed, the human dimensions appear from the moment where the interaction becomes the center of interest (“IIR” for “Interaction Information Retrieval”). Some authors also propose a historical reading of the evolution of theoretical frameworks and methodological studies, for example, noting the evolution of topics discussed during important international scientific events [BEA 96, OVE 01].

The links between information retrieval and navigation are so narrow that the terms are often used interchangeably. From a formal point of view, navigation encompasses the whole range of techniques and procedures that allow, on the one hand, finding the position of a moving object in relation to a reference system or a fixed point and, on the other hand, calculating and measuring the route of a given point to another point. The moving object can be a human individual or an object, depending on the case.

For some, navigation is one of the elements of information retrieval: for example, it is by navigating from one Web page to another Web page that information is retrieved. For others, it is information retrieval that is one of the navigation elements: it is by searching for and retrieving the relevant information in the environment (physical or digital) that we can navigate. This design corresponds to that presented in studies about driving cars, piloting aircraft, operating machinery or even the movement of pedestrians or users in physical or digital environments. In all these areas, navigation is the final objective and information retrieval is one of the processes and/or one of the underlying phases to achieve the objective. We can point out that many metaphors borrowed from aerial or maritime navigation (in physical environments) are always applied to the design of digital environments [AHU 01, CHE 11, EDW 89, MCD 98, SMI 96]: the navigation bar, the portal, the compass, etc.

1.4. Why should we be interested in information retrieval?

Ergonomic psychology and ergonomics are not the only disciplines in the field of social and human sciences (SHS) that are interested in information retrieval. The activity of information retrieval is also the subject of many studies in the disciplines of management sciences or even engineering.

Although that may seem very distant from the approaches of psychology and ergonomics, we present very briefly the contributions of three disciplines whose knowledge is related to the activity of information retrieval in digital environments: economics, computer science and robotics. Most importantly, we present why these disciplines are very interested in the activity of information retrieval.

1.4.1. Economy: maximize profitability and minimize risks

In the business world, information retrieval is a crucial activity. Indeed, corporate decision-making can only be done after a substantial work of information retrieval. The increase of pressure related to competition, time constraints, information load as well as the geographical dispersion of information have made the phases of information retrieval even more dominant [DAV 05, KAI 91].

In a survey conducted in 2009 by an important group at the junction of marketing and technology (Delphi Group: http://www.delphigroup.com), 1,030 employees of 15 US companies of medium size responded that they spent more than a third of their working time searching for information. Yet, these employees did not belong to a document and/or information survey service. These results coincide with those obtained by McDermott [MCD 05], which show that 38% of employees of large companies spend the majority of their time searching for information. The importance of information retrieval not only affects large firms: it appears that professionals from other sectors spend increasingly more time searching for information, such as teachers, health professionals or even lawyers [COO 06].

According to an internal report of G...