eBook - ePub

Metropolitan Preoccupations

The Spatial Politics of Squatting in Berlin

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this, the first book-length study of the cultural and political geography of squatting in Berlin, Alexander Vasudevan links the everyday practices of squatters in the city to wider and enduring questions about the relationship between space, culture, and protest.

- Focuses on the everyday and makeshift practices of squatters in their attempt to exist beyond dominant power relations and redefine what it means to live in the city

- Offers a fresh critical perspective that builds on recent debates about the "right to the city" and the role of grassroots activism in the making of alternative urbanisms

- Examines the implications of urban squatting for how we think, research and inhabit the city as a site of radical social transformation

- Challenges existing scholarship on the New Left in Germany by developing a critical geographical reading of the anti-authoritarian revolt and the complex geographies of connection and solidarity that emerged in its wake

- Draws on extensive field work conducted in Berlin and elsewhere in Germany

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Metropolitan Preoccupations by Alexander Vasudevan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Introduction: Making Radical Urban Politics

Considering there are houses standing empty,

While you leave us homeless on the street,

We've decided that we're going to move in now,

We're tired of having nowhere dry to sleep.

While you leave us homeless on the street,

We've decided that we're going to move in now,

We're tired of having nowhere dry to sleep.

Considering you will then

Threaten us with cannons and with guns,

We've now decided to fear

A bad life more than death.

Threaten us with cannons and with guns,

We've now decided to fear

A bad life more than death.

Bertolt Brecht (1967: 655)1

We don’t need any landowners because the houses belong to us.Ton Steine Scherben (1972)2

On the evening of 1 May 1970, a small theatre troupe began an impromptu performance in the middle of a shopping district in a newly-built satellite city on the northern outskirts of West Berlin. The troupe, Hoffmann’s Comic Teater, was a radical theatre ensemble formed in 1969 by three brothers, Gert, Peter and Ralph Möbius, at the height of the countercultural ‘revolution’ in West Germany. Wearing colourful costumes and masks and accompanied by a live band, they soon developed a reputation for staging politically daring events that took place in the streets of West Berlin and in the city’s many youth homes (Brown, 2013: 172; see Sichtermann, Johler, Stahl, 2000; Seidel, 2006). The performances focused, in particular, on the everyday conflicts that shaped the lives of Berlin’s working-class residents. Audience participation was actively encouraged by the troupe who developed an engaged agitprop style in which “the predominant cultural and political consciousness of the audience member” became the “starting point for the planning and realisation of the play” (quoted in Brown, 2013: 173). Scenes were improvised while spectators were invited onto the ‘stage’ to act out scenes from their own lives.

On 1 May 1970, the troupe travelled to the Märkisches Viertel, a large modernist housing estate in the district of Reinickendorf whose construction was part of West Berlin’s First Urban Renewal Programme initiated by then Mayor Willi Brandt in 1963. The programme was responsible for the widespread demolition of inner-city tenements and the ‘decanting’ of their predominantly working-class occupants – approximately 140,000 Berliners – to new tower block estates on the fringes of the city (see Pugh, 2014; Urban, 2013). The performance by Hoffmann’s Comic Teater focused, unsurprisingly, on the experience of the estate’s residents and their anger at the lack of social infrastructure and the unwillingness of state-operated landowner and developer GESOBAU to provide “free spaces (Freizeiträumen)” for local youth.3 It concluded with a scene that dramatised the recent closure of an after-school club (Schülerladen) after which the participants and spectators were encouraged to occupy a nearby building as a symbolic protest against GESOBAU. They were prevented from doing so, however, by the police who had been following the performance and had already secured the site. A group of over one hundred activists, performers and other local residents were nevertheless able to stage an occupation in an adjoining factory. As they began discussions over the formation of an autonomous self-organised youth centre, the factory hall was stormed by riot police and the occupiers, who included the journalist Ulrike Meinhof, brutally evicted. Three protesters were seriously injured and taken to hospital (see Figure 1.1).4

Figure 1.1 Arrest of the journalist Ulrike Meinhof at a protest occupation in the Märkisches Viertel in West Berlin, 1 May 1970 (Klaus Mehner, BerlinPressServices).

In the immediate aftermath of the eviction, a small group of local activists initiated a discussion about the future direction of political mobilising in the Märkisches Viertel. A strategy paper was produced and circulated by the group who criticised the new housing estate and its developers for their insufficient attention to the needs and desires of its tenants (Beck et al., 1975). One of the authors of that unpublished paper was Meinhof, who only two weeks later would take part in the breakout of Andreas Baader from the reading room of the Social Studies Institute of West Berlin’s Free University (Freie Universität), an event which led to the formation of the Red Army Faction (Rote Armee Faktion or RAF) (Aust, 1985).5 Hoffmann’s Comic Teater continued to produce engaged performances in the wake of the occupation and also turned their attention to children’s theatre (see Möbius, 1973). Members of the group were later involved in the formation of Ton Steine Scherben, one of the most important bands within the radical scene in West Berlin and whose history is largely inseparable from the evolution of the anti-authoritarian Left in the city (Brown, 2009). While the factory occupation in the Märkisches Viertel was itself short-lived, it was nevertheless the first squatted space in a city where the radical politics of occupation would soon assume a new and enduring significance.

The story behind Berlin’s first squat brings together a number of themes that are at the heart of this book: namely, the turn to squatting and occupation-based practices, more generally, as part of the repertoire of contentious performances adopted by activists, students, workers and other local residents across West Germany during the anti-authoritarian revolt of the 1960s and 1970s and in its wake; the relationship between the emergence of the New Left in West Germany and the transformation of Berlin into a veritable theatre of dissent, protest and resistance (see Davis, 2008); the recognition of uneven development and housing inequality as a source of political mobilisation and the concomitant privileging of concrete local struggles in Berlin for the composition of new spaces of action, self-determination and solidarity; and, finally, the widespread desire to reimagine and live the city differently and to reclaim a ‘politics of habitation’ and an alternative ‘right to a city’ shaped by new intersections and possibilities (Lefebvre, 2014, 1996; see also Simone, 2014; Vasudevan, 2011a; Vasudevan, 2014a).6

In the pages that follow, I develop a close reading of the history of squatting in Berlin. To do so, the book charts the everyday spatial practices and political imaginaries of squatters. It examines the assembling of alternative collective spaces in the city of Berlin and takes in developments in both former West and East Berlin. For squatters, the city of Berlin came to represent both a site of political protest and creative re-appropriation. The central aim of the study is to show how the history of squatting in Berlin formed part of a broader narrative of urban development, dispossession and resistance. It draws particular attention to the ways in which squatting and other occupation-based practices re-imagined the city as a space of refuge, gathering and subversion. This reflects the fulsome emergence of new social movements in the 1960s and 1970s in West Germany as well as the tentative development of an alternative public sphere in the final years of the German Democratic Republic (see Brown, 2013; Davis, 2008; Klimke, 2010; Moldt, 2005, 2008; Reichardt, 2014; Thomas, 2003). At the same time, it is a story that speaks to a renewed form of emancipatory urban politics and the possibility of forging new ways of thinking about and inhabiting the city that extend well beyond Berlin and, for that matter, Germany.

As the first book-length study of the cultural and political geographies of squatting in Berlin, this is a project that seeks to develop a rich historical account of the various struggles in the city over the making of an alternative urban imagination and the search for new radical solutions to a lack of housing and infrastructure. The book focuses, in particular, on what squatters actually did, the terms and tactics they deployed, the ideas and spaces they created. This is a history, in turn, that has had a significant impact on the transformation of Berlin’s urban landscape and has shaped recent struggles over the city’s identity. As I argue, squatters and the spaces they occupied were never incidental minor details in the formation and evolution of the New Left in West Germany in the 1960s and the various social movements which developed in the decades that followed. They played, if anything, a vital role in opening up new perspectives on the very form and substance that radical political action and solidarity could assume and are supported, in turn, by figures that point to an alternative milieu made up of thousands of activists and an even larger circle of sympathisers (Amantine, 2012; Azozomox, 2014a, n.d; see also Reichardt, 2014 for a wider perspective).

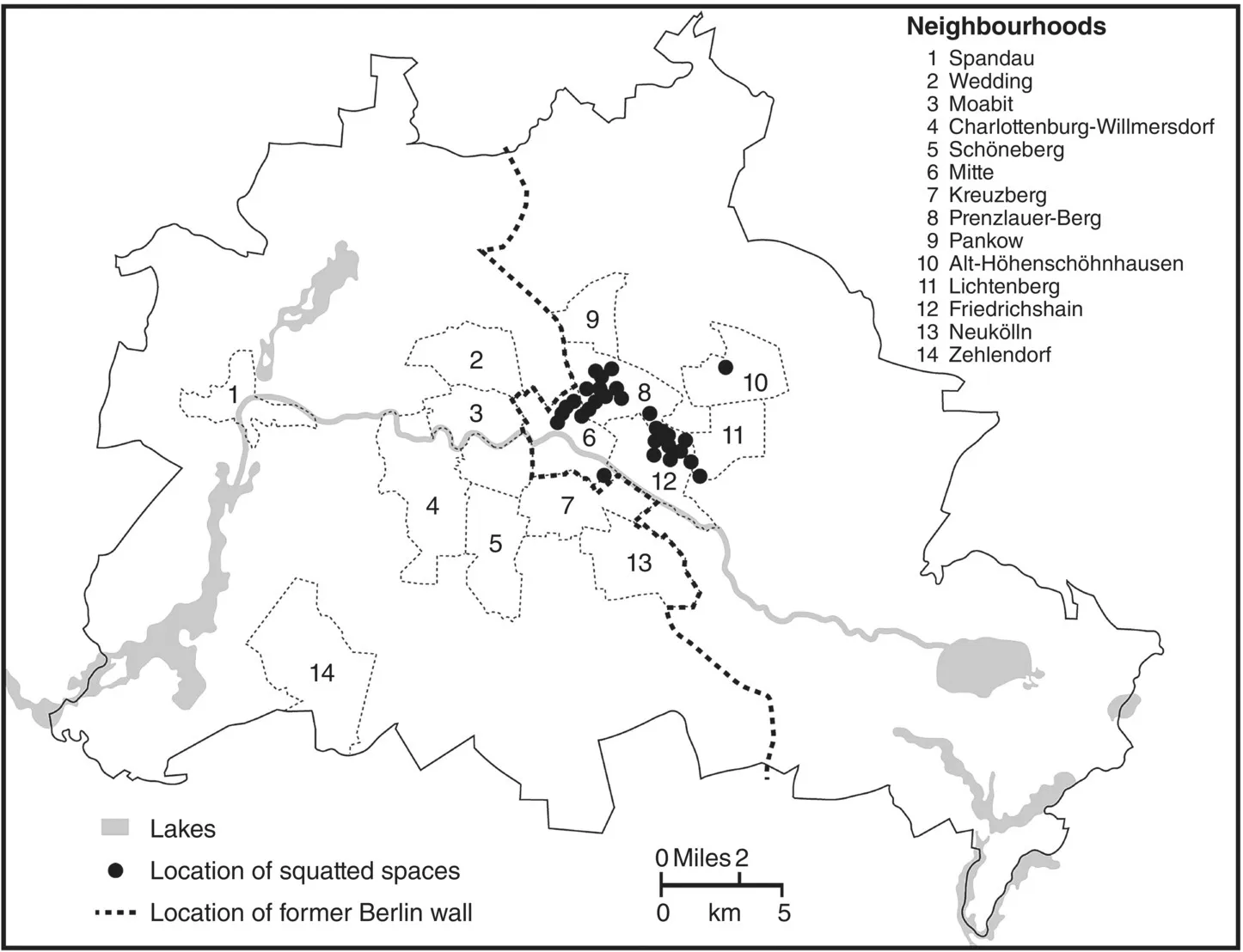

In Berlin, there have been at least 610 separate squats of a broadly political nature between 1970 and 2014 (see Figures 1.2 and 1.3). The majority of these actions took place in the city’s old tenement blocks although they also encompassed a range of other sites from abandoned villas, factories and schools, to parks, vacant plots and even, in one case, a part of the ‘death strip’ that formed the border between West and East Berlin. As a form of illegal occupation, squatting typically fell under §123 of the German Criminal Code (“Trespassing”) though many magistrates in Berlin as well as elsewhere in West Germany were reluctant to charge squatters as, in their eyes, a run-down apartment did not satisfy the legal test for an apartment or a “pacified estate (befriedetes Besitztum)” (Schön, 1982).7 There were, in this context, two major waves of squatting in the city. The first wave between 1979 and 1984 involved 265 separate sites as activists and other local residents responded to a deepening housing crisis by occupying apartments, the overwhelming majority of which were located in the districts of Kreuzberg and Schöneberg. At the high point of this wave in the spring of 1981, it is estimated that there were at least 2000 active squatters in West Berlin and tens of thousands of supporters (Reichardt, 2014: 519). The second wave between 1989 and 1990 shifted the gravity of the scene to the former East as hundreds of activists exploited the political power vacuum that accompanied the fall of the Berlin Wall, squatting 183 sites both in the former East as well as the West.8 Since 1991, there have been only 100 occupations across Berlin as local authorities have vigorously proscribed and neutralised attempts to squat. Of these squats, 56 were evicted by the police within four days. Overall, 200 spaces have been legalised and, in 35 cases, the squatters have themselves acquired ownership (see Azozomox, n.d.).9 While these figures point to the sheer scale and intensity of squatting in Berlin, they do not take into account other forms of deprivation-based squatting carried out by homeless people nor do they include the large number of East Berliners who, from the late 1960s to the end of GDR, illegally occupied empty flats in response to basic housing needs, a process that was known as ‘Schwarzwohnen’ (Grashoff, 2011a, 2011b; Vasudevan, 2013).10

Figure 1.2 Map of squatted spaces in West Berlin up to the end of 1981. Map produced by Elaine Watts, University of Nottingham.

Figure 1.3 Map of the second wave of squatting in the former East of Berlin, 1989–1990. Map produced by Elaine Watts, University of Nottingham.

As these figures suggest, the history of squatting in Berlin occupied a significant place within a complex landscape of protest in the city. At the same time, the squatter ‘movement’ that emerged in Berlin was also connected to similar scenes in other West German cities in the 1970s and 1980s – most notably Frankfurt, Freiburg and Hamburg – and to a number of cities in the former East in the early 1990s (Dresden, Halle, Leipzig and Potsdam) (see Amantine, 2012; Dellwo and Baer, 2012, 2013; Grashoff, 2011b). It is perhaps surprising, therefore, that there remains little empirical work on the role of squatting – and the built form and geography more generally – in the creation and circulation of new activist imaginations and the production of collective modes of living. Why, in other words, did thousands of activists and citizens choose to break the law and occupy empty flats and other buildings across Germany and Berlin, in particular? Were these actions dictated by pure necessity or did they represent a newfound desire to imagine other ways of living together? Who were these squatters? What were the central characteristics of urban squatting (goals, action repertoires, political influences)? And in what way did these practices promote an alternative vision of the city as a key site of “political action and revolt” (Harvey, 2012: 118–119)?

In order to answer these questions, the study develops a conceptually rigorous and empirically grounded approach to the emergence of squatting in Berlin. More specifically, it develops three interrelated perspectives on the everyday practices of squatters in the city and their relationship to recent debates about the ‘right to the city’ and the potential for composing other critical urbanisms (see Attoh, 2011; Harvey, 2008, 2012; Lefebvre, 1996; Mitchell, 2003; Nicholls, 2008; Purcell, 2003; Vasudevan, 2014a). Firstly, it signals a challenge to existing historical scholarship on the New Left in Germany by arguing that the time has come to spatialise the events, practices and participants that shaped the history of the anti-authoritarian revolt and to retrace the complex geographies of connection and solidarity that were at its heart. Secondly, it draws attention to squatted spaces as alternative sites of habitation, that speak to a radically different sense of ‘cityness’, i.e. a city’s capacity to continuously reorganise and structure the ways in which people, places, materials and ideas come together (Simone, 2010, 2014). Thirdly, it places particular emphasis on the material processes – experimental, makeshift and precarious – through which squatters came together as a social movement, sometimes successfully, sometimes less so. At stake here is a critical understanding and detailed examination of the conceptual resources and empirical domains through which an alternative right to the city is articulated, lived and contested (McFarlane, 2011b). A large part of this effort is, in turn, predicated on identifying concrete ways to recognise and represent the various efforts of squatters whilst acknowledging their complexity, contradictions, successes, and failures (see Simone, 2014: xi). To do so, the book ultimately argues, is to also draw wider lessons for how we, as geographers and urbanists, come to understand the city as a site of political contestation.

Spatialising the Anti-Authoritarian Revolt

In recent years, the historical development of the New Left in West Germany has bec...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Series Editors’ Preface

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One: Introduction: Making Radical Urban Politics

- Chapter Two: Crisis and Critique

- Chapter Three: Resistance and Autonomy

- Chapter Four: Antagonism and Repair

- Chapter Five: Separation and Renewal

- Chapter Six: Capture and Experimentation

- Chapter Seven: Conclusion: “Der Kampf geht weiter”

- References

- Index

- End User License Agreement