Wound Healing

Stem Cells Repair and Restorations, Basic and Clinical Aspects

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

A comprehensive resource on the recent developments of stem cell use in wound healing

With contributions from experts in the field, Wound Healing offers a thorough review of the most recent findings on the use of stem cells to heal wounds. This important resource covers both the basic and translational aspects of the field. The contributors reveal the great progress that has been made in recent years and explore a wide range of topics from an overview of the stem cell process in wound repair to inflammation and cancer. They offer a better understanding of the identities of skin stem cells as well as the signals that govern their behavior that contributes to the development of improved therapies for scarring and poorly healing wounds.

Comprehensive in scope, this authoritative resource covers a wealth of topics such as: an overview of stem cell regeneration and repair, wound healing and cutaneous wound healing, the role of bone marrow derived stems cells, inflammation in wound repair, role and function of inflammation in wound repair, and much more. This vital resource:

- Provides a comprehensive overview of stem cell use in wound healing, including both the basic and translational aspects of the field

- Covers recent developments and emerging subtopics within the field

- Offers an invaluable resource to clinical and basic researchers who are interested in wound healing, stem cells, and regenerative medicine

- Contains contributions from leading experts in the field of wound healing and care

Wound Healing offers clinical researchers and academics a much-needed resource written by noted experts in the field that explores the role of stem cells in the repair and restoration of healing wounds.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Stem Cell Regeneration and Repair – Overview

Introduction

Overview of Skin Wound Healing

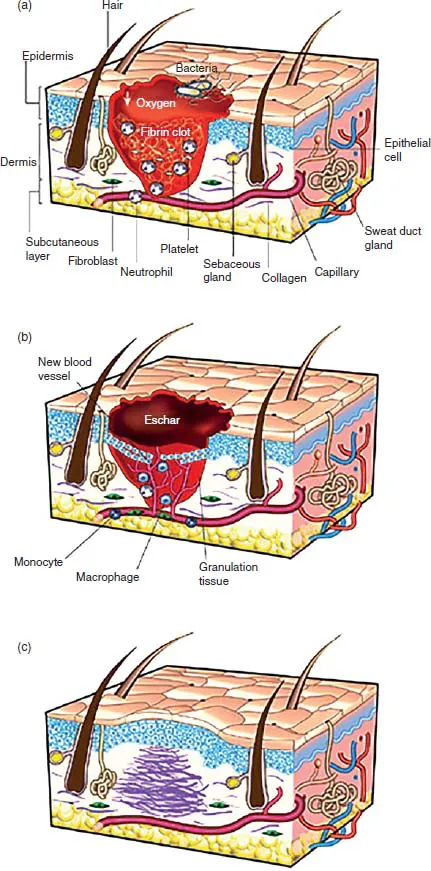

(a) Inflammation. This stage lasts until about 48 h after injury. Depicted is a skin wound at about 24–48 h after injury. The wound is characterized by a hypoxic (ischaemic) environment in which a fibrin clot has formed. Bacteria, neutrophils, and platelets are abundant in the wound. Normal skin appendages (such as hair follicles and sweat duct glands) are still present in the skin outside the wound. (b) New tissue formation. This stage occurs about 2–10 days after injury. Depicted is a skin wound at about 5–10 days after injury. An eschar (scab) has formed on the surface of the wound. Most cells from the previous stage of repair have migrated from the wound, and new blood vessels now populate the area. The migration of epithelial cells can be observed under the eschar. (c) Remodeling. This stage lasts for a year or longer. Depicted is a skin wound about 1–12 months after repair. Disorganized collagen has been laid down by fibroblasts that have migrated into the wound. The wound has contracted near its surface and the widest portion is now the deepest. The re-epithelialized wound is slightly higher than the surrounding surface and the healed region does not contain normal skin appendages. (Reproduced from Gurtner et al. [1], with permission from Nature Publishing Group.)

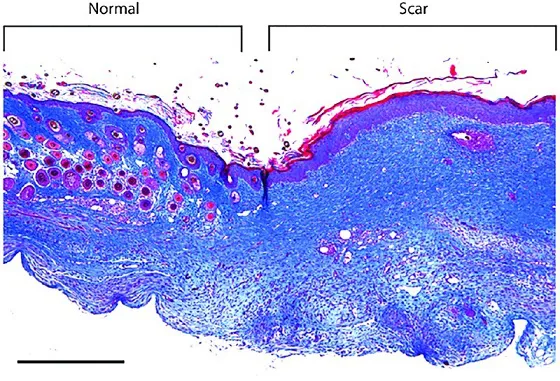

Normal skin contains hair follicles and other dermal appendages. Scarred skin does not contain these appendages and the epidermis is flattened. Note that that scarred dermis is thicker than the normal dermis. Scale bar, 500 μm.

Stem Cell Definition: History

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Chapter 1 Stem Cell Regeneration and Repair – Overview

- Chapter 2 Cadherins as Central Modulators of Wound Repair

- Chapter 3 Tight Junctions and Cutaneous Wound Healing

- Chapter 4 The Role of Microvesicles in Cutaneous Wound Healing

- Chapter 5 Wound Healing and Microenvironment

- Chapter 6 Wound Healing and the Non-cellular Microenvironment

- Chapter 7 Contribution of Adipose-Derived Cells to Skin Wound Healing

- Chapter 8 Role of Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells in Wound Healing

- Chapter 9 Role of Vitamin D and Calcium in Epidermal Wound Repair

- Chapter 10 Oral Mucosal Healing

- Chapter 11 Role of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells in Wound Healing: An Update from Isolation to Transplantation

- Chapter 12 The Hair Follicle as a Wound Healing Promoter and Its Application in Clinical Practice

- Chapter 13 Impaired Wound Healing in Diabetic Ulcers: Accelerated Healing Through Depletion of Ganglioside

- Chapter 14 Inflammation in Wound Repair: Role and Function of Inflammation in Wound Repair

- Chapter 15 Inflammation, Wound Healing, and Fibrosis

- Chapter 16 The Potential Role of Photobiomodulation and Polysaccharide-Based Biomaterials in Wound Healing Applications

- Chapter 17 Is Understanding Fetal Wound Repair the Holy Grail to Preventing Scarring?

- Chapter 18 Inflammation and Cancer

- Index

- EULA