eBook - ePub

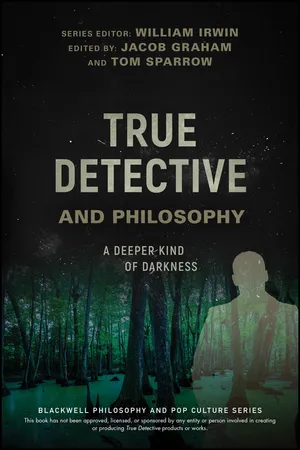

True Detective and Philosophy

A Deeper Kind of Darkness

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

True Detective and Philosophy

A Deeper Kind of Darkness

About this book

Investigating the trail of philosophical leads in HBO's chilling True Detective series, an elite team of philosophers examine far-reaching riddles including human pessimism, Rust's anti-natalism, the problem of evil, and the 'flat circle'.

- The first book dedicated to exploring the far-reaching philosophical questions behind the darkly complex and Emmy-nominated HBO True Detective series

- Explores in a fun but insightful way the rich philosophical and existential experiences that arise from this gripping show

- Gives new perspectives on the characters in the series, its storylines, and its themes by investigating core questions such as: Why Life Rather Than Death? Cosmic Horror and Hopeful Pessimism, the Illusion of Self, Noir, Tragedy, Philosopher-Detectives, and much, much more

- Draws together an elite team of philosophers to shine new light on why this genre-expanding show has inspired such a fervently questioning fan-base

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access True Detective and Philosophy by Jacob Graham, Tom Sparrow, Jacob Graham,Tom Sparrow, William Irwin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

“IT'S ALL ONE GHETTO, MAN … A GIANT GUTTER IN OUTER SPACE”

Pessimism and Anti-natalism

1

Why Life Rather than Death?:

Answers from Rustin Cohle and Arthur Schopenhauer1

Sandra Shapshay

Rustin Cohle, the protagonist of the first season of True Detective, declares that he is “in philosophical terms, a pessimist.” Before we are introduced to him, Rust has already experienced the terrible loss of his two-year-old daughter and the painful dissolution of his marriage. His employment confronts him daily with the horrors of human conduct, where the “law of the stronger” reigns and the strong and sadistic exploit the weak and vulnerable. Throughout season one, we see Rust struggling to find the best, truest response to all this seemingly endemic and unredeemed suffering.

Rust thinks that human consciousness is a “tragic misstep in nature.” The doctrine of “pessimism” espoused by Rust is remarkably similar to the view adumbrated by Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860), who holds that (1) conscious life (both human and nonhuman animal) involves a tremendous amount of suffering that is essentially built into the structure of the world and (2) there is no Creator (providential or otherwise) to redeem all of this suffering, by, say, punishing the wicked and rewarding the good.

Arthur Schopenhauer's Pessimism

Schopenhauer is just as attuned as Rust to the tremendous amount of evil in the world, caused for the most part by other human beings. Whereas the “true detective” is nauseated and jaded by the sadistic acts of bayou killers who prey mostly on innocent girls and young women, Schopenhauer is nauseated and jaded by more institutional sources of human suffering in nineteenth-century Europe and the United States that spring largely from pervasive human egoism and, to a lesser but not insignificant extent, malice:

The chief source of the most serious evils affecting man is man himself; homo homini lupus. He who keeps this last fact clearly in view beholds the world as a hell, surpassing that of Dante by the fact that one man must be the devil of another. … How man deals with man is seen, for example, in Negro slavery, the ultimate object of which is sugar and coffee. However, we need not go so far; to enter at the age of five a cotton-spinning or other factory, and from then on to sit there every day first ten, then twelve and finally fourteen hours, and perform the same mechanical work, is to purchase dearly the pleasure of drawing breath. But this is the fate of millions, and many more millions have an analogous fate.2

Additionally, Schopenhauer focuses on the suffering of nonhuman animals at the hands of human beings who view them as mere instruments for their use:

Because … Christian morals give no consideration to animals, they are at once free as birds in philosophical morals too, they are mere “things”, mere means to whatever ends you like, as for instance vivisection, hunting with hounds, bull-fighting, racing, whipping to death in front of an immovable stone-cart and the like.3

Why Not Suicide?

Given this grim view of the human condition, it makes sense to raise the question of suicide: Why not put an end to one's life, in order to escape from this ultimately senseless vale of tears? Throughout True Detective, Rust struggles with “letting go” and, regarding the last episode of season one, “Form and Void,” the creator, Nic Pizzolatto, explains that the episode “represents the dilemma Rust walked for some time: why life rather than the opposite?”4 Rust thinks that our “programming” (in Schopenhauer's terms, the “will-to-live”) “gets us out of bed in the morning” but that it would be better, all things considered, to “deny our programming” and walk ourselves “hand in hand into extinction” (“The Long Bright Dark”). Thus, Rust enunciates his in principle embrace of suicide.

In this positive attitude toward suicide, Rust actually parts ways with Schopenhauer, which is surprising since the philosopher is one of the most famous pessimists in the history of Western thought. In fact, Schopenhauer regarded suicide as a “futile and foolish act.”5 What accounts for this divergence?

Schopenhauer's Answer

Schopenhauer does not discourage suicide out of philosophical optimism: he doesn't think that this is the best of all possible worlds, as Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716) does; neither does he believe that the world must get better because of a necessary rational structure, as Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) holds; nor that the world is a self-justifying divine cause, as Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) argues. Also, he doesn't see life as a gift, to be thankfully accepted. Schopenhauer is convinced that the world is and will always be full of unredeemed suffering, for nature involves an internecine struggle for existence rather than a “peaceable kingdom” of animals living largely in harmony. And he is convinced that much of this suffering will go uncompensated in this life, as the sources of suffering seem to outweigh the sources of happiness and tranquility. Above all, he is an uncompromising atheist who holds that there is no providential God to redeem all of this suffering in an afterlife.

It might be surprising, then, that Schopenhauer thinks suicide is a “futile and foolish act.” Perhaps, like Rust, Schopenhauer should embrace suicide. For the nature of the will-to-live is ultimately blind, senseless striving and suffering for no particular end. Yet the reason Schopenhauer rejects suicide is that suicide does not negate but rather affirms the will-to-live, for the person who would die by suicide desires life; it's just that the individual is unsatisfied with the conditions on offer for their particular life. Within this logic, suicide is foolish because it prevents a person from attaining the highest wisdom and the true inner peace that would come from actual renunciation of the will-to-live. Thus, Schopenhauer writes, suicide is “an act of will” through which “the individual will abolishes the body … before suffering can break it.” He thereby likens a suicidal person to a sick person who “having started undergoing a painful operation that could cure him completely, does not allow it to be completed and would rather stay sick.”6 There is only one remarkable exception to his overall view on suicide: death by voluntary starvation. At the highest levels of asceticism, the negation of the will-to-live can attain such a point where “even the will needed to maintain the vegetative functions of the body through nutrition can fall away.”7

Rust's Answer

Returning to True Detective, we see that Rust struggles with many of the same issues that occupy Schopenhauer. For instance, though Rust embraces pessimism and resignationist tendencies, as evidenced by his rather ascetic lifestyle and in principle embrace of suicide, Rust does not actually resign himself from life. He is, after all, the eponymous “true detective” and throws himself assiduously into the task of solving the ritualistic rapes and murders and bringing the perpetrators to justice.

So what really motivates Rust to spend most of his waking life (and he doesn't seem to sleep all that much) attempting to solve these crimes? Is it the intellectual puzzle? Is it compassion for the victims and potential new victims? Is it a thirst for justice?

At times it seems that it is merely the intellectual challenge that motivates Rust. This recalls Schopenhauer's own expressed reason to devote himself to philosophy: “Life is an unpleasant business; I have resolved to spend it reflecting upon it.”8 Yet, what preoccupies Rust's mind and takes up a good bit of wall space in his barely furnished apartment is reflection with a specific practical aim—namely, to solve the crimes in order to prevent future victims and to bring the perpetrators to justice.

Thus, Rust seems not just motivated by the intellectual puzzle but also by a morality of compassion and justice. After all, his aim is not merely to solve the crimes but also to apprehend or otherwise stop the perpetrators. Further, these moral motives get to the heart of Rust's espousal of pessimism in the first place, for he is—unlike how Marty often seems—acutely sensitive to the sufferings of others and—again, unlike Marty but in line with Schopenhauer—rejects any theological story of redemption for all of this suffering.

What I want to suggest, then, is that Rust's own practice belies his stated pessimistic views. It is not just “programming”—the will-to-live, egoistic striving—that gets Rust out of bed in the morning; rather, it is the sense that if there is to be any kind of redemption it has to be earthly, in the form of prevention or alleviation of suffering, and in bringing criminals to justice.

Schopenhauer on Compassion

Surprisingly, Schopenhauer at certain points in his writings seems to recommend the general, compassionate, and justice-seeking path that Rust takes in True Detective. Especially in his underappreciated essay “On the Basis of Morality,” Schopenhauer recommends acts of justice and loving-kindness in response to the myriad sources of misery. For example, he praises the British nation's spending “up to 20 million pounds” to buy the freedom of slaves in America.9 He also champions the proliferation of animal protection societies in Continental Europe, recommending English newspaper reports to address “the associations against the torture of animals now established in Germany, so that they see how one must attack the issue if anything is to come of it” and he acknowledges “the praiseworthy zeal of Councillor Perner in Munich who has devoted himself entirely to this branch of beneficence and spread the initiative for it throughout the whole of Germany.”10

Finally, Schopenhauer recognizes that the work of civic organizations, especially in securing legal change, can brin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Introduction: Welcome to the Psychosphere

- Part I “IT'S ALL ONE GHETTO, MAN … A GIANT GUTTER IN OUTER SPACE”: Pessimism and Anti-natalism

- Part II “We Get the World We Deserve”: Cruelty, Violence, Evil, and Justice

- Part III “Everybody's Nobody”: Consciousness, Existence, and Identity

- Part IV “This Is My Least Favorite Life”: Noir, Tragedy, and Philosopher-Detectives

- Part V “Time Is a Flat Circle”: Time in True Detective

- Known Associates

- Index

- EULA