One

Managers in the Middle

This book is about empowerment, which is giving people as much control as possible over how their work gets done. One of the forces drawing us toward empowerment for people in the middle and lower levels of organizations is the fact that most large companies, because of technology, automation, and cost pressure, have for decades been reducing the number of employees as fast as they can, often eliminating whole layers of management in their attempt to be more efficient. Plus there has been a relentless growth of outsourcing and virtual jobs. People work at home, long distance, and in multiple time zones. We would think this would work to further disperse the centralization of power. That it would push responsibility downward and result in a direct assault on the bureaucratic methods and the patriarchal mind-set that characterize life in most organizations.

Reducing bureaucracy and building accountability requires more than simply reducing jobs and becoming more lean and agile. It requires a mind-set shift on the part of managers, workers, and people at any level. The attitude shift is toward feeling empowered to exercise choice in service of the business and themselves. At the deepest level, the enemy of high-performing systems is the feeling of helplessness that so many of us in organizations seem to experience. We are caught between the need for managers and workers to stand firm for their beliefs and yet realize there are always people who have power over us and can blow out our candle without even taking a deep breath.

The simplest way to capture the dilemma this book addresses is by telling you the story of Allan. Allan is a top executive who, for me, symbolizes both the deepest hope we have for what organizations can become as well as the harsh reality of what each of us confronts. When I first met Allan he was a group product manager for a large health care company. He was in his mid-thirties and responsible for the marketing of a line of health care products. Allan knew his business, and was very aggressive in both his approach to the marketplace and his approach to the people around him. He was constantly pushing for changes in the way the company did business. His product line consistently met its financial goals, but his rather impatient, task-oriented, and at times judgmental style of operating began to get him in hot water. He was told that he needed to become more of a team player, was pushing against the structure a little too vigorously, and if he could just ease up a bit, he would have a fine career with this company.

This dialogue finally reached a point at which a promotion was withheld because of the feathers he was ruffling. At the same time a proposal Allan had made to bring a new product to market was put on a back burner. In the face of these two setbacks, Allan bolted. He initiated a job search for an organization that would value his entrepreneurial energy and give him the opportunity to initiate a truly successful new venture. His search uncovered a pharmaceutical company that was looking to move into new businesses. The head of the company offered Allan the opportunity to study the feasibility of this new business, and if the company decided to move ahead, Allan would run the new division. Allan took the job, leaving the health care company with some bitterness and the belief that its bureaucratic mentality was the problem.

The pharmaceutical company decided to go ahead with the new venture and Allan was made president of the new division. Allan was determined to build an entrepreneurial organization in the midst of the conservative pharmaceutical company that he recently joined. His goal was to hire people who were willing to take the risk of an entrepreneurial venture and to create a culture that valued initiative, absolute honesty, and achievement. Every organization says it values these qualities, but Allan wanted to make these entrepreneurial ideals a day-to-day reality.

Over the next four years, Allan became first a client and eventually a friend of mine. With my role as social architect, we devised as many ways as we could think of to structure the organization to encourage people to feel empowered and responsible for the success of the business. A reward system was established whereby a significant part of each person's salary was based on the profitability of the division. Allan pushed decision-making to the lowest level. The staff made all its own decisions about equipment, structure, working procedures, performance criteria, and evaluation. Perquisites such as office size and decor, parking spaces, vacation time, eating areas, and the like were the same for everyone in the company, including Allan. Every action and policy was designed to create an alternative to the cautious, nervous, and political environments in which everyone had previously worked.

Despite some ups and downs, the strategy essentially worked. The division became profitable after two years and passed $40 million in sales in the third year. Needless to say, Allan was an ideal client for me and became a role model for many of the ideas that this book expresses. The experience with Allan gave me faith that it is indeed possible to create an organization of our own choosing even though we are surrounded by an organization steeped in conservative tradition. Throughout this process, Allan was forced to constantly defend and explain the way he was managing his division. The more successful the division became, the more attention it got, and the greater the discomfort his practices created among other executives in the company. But the bottom line was that he had created an entrepreneurial unit and even though the number of people in the division was growing rapidly, the spirit survived.

How I wish that the story ended here, but it doesn't. As I was completing an earlier version of this book about people taking responsibility, being political in a positive way, and not getting caught up in the negative politics surrounding them, I got a phone call from Allan.

He had just had a meeting with his boss, an executive vice president of the parent company, and been asked to resign. He was told that top management had been growing increasingly uncomfortable with him, that the chemistry wasn't good, and that top management had decided to replace Allan with one of his subordinates. In the previous six months, Allan's division had come under increasing scrutiny and Allan had evidently responded with considerable aggression, some anger, and probably more than a little arrogance––all qualities we tend to associate with entrepreneurial, individualistic people. Allan took his exit quite well. He was getting weary of having to defend his actions and, in fact, took more pleasure in creating a business than in maintaining it.

I, however, took his demise quite poorly. How could he do this to me? Here I was writing a book using him as one of my positive role models and he goes and gets himself fired. The least he could have done was to wait until the early version of the book was published before he crashed and burned. I did not express my self-centered concerns to Allan on the phone at that time. I expressed my support and wished him well, knowing that he would land on his feet, which he did. Two months later, he finalized a deal whereby he would start up another health care company for some venture capitalists and he would have total control over the business and no accountability other than profitability. A couple of ventures later, his business went public and Allan did well.

His problem was solved, but the dilemma that is the focus of this book is not. Allan's dilemma in the pharmaceutical company is the same one facing anyone who manages a group as part of a larger organization. There is a bit of Allan in each of us. On the one hand we have strong beliefs about how we want to manage our own unit; on the other hand we have people above and around us who wish us to be much more traditional and cautious. They counsel us to be patient, to be sensitive to the wishes of people in power, and they remind us that change is all around us, but to get on board and be a team player. The meaning of Allan's story is that it speaks to a hope and a fear in each of us. The hope is that we can totally be ourselves and act according to our own beliefs and wants and still be valued. We have hopes to improve our organization and make it a place where people take responsibility, where reasonable risks are valued, where getting results is more important than pleasing others, and where substance is more important than form. At the same time, we fear that this is not possible. We are afraid that Allan's ending will be our ending, except that we will not land on our feet. We will land on our knees and stay there. Especially when we see the middle class and upwardly mobile careers shrinking all around us. Our primitive fear in organizations is that if we stand up, we will be shot. This book is about standing up without getting shot.

The goal, then, is to present a way of transforming organizations with the attendant risks, in a realistic and helpful way. Making changes in organizations in a way that maintains support from those around us is what empowerment is all about. The first step in taking the best of what Allan offers—his courage, his vision, his willingness to risk—without stepping on the rake of our own arrogance and aggression, is to begin a dialogue about the political nature of institutions.

Part One

Politics in the Workplace:

Rekindling the Entrepreneurial Spirit

There is no more engaging and volatile aspect of work life than the dimension of organizational power for which the word politics is shorthand. In most places, people are not comfortable discussing politics openly. We know it is woven into the fabric of our work, but to get reliable information about it is next to impossible. In fact, the first rule of politics is that nobody will tell you the rules. When it is discussed, it is basically a negative process. If I told you that you were a very political person, you would take it either as an insult or at best as a mixed blessing.

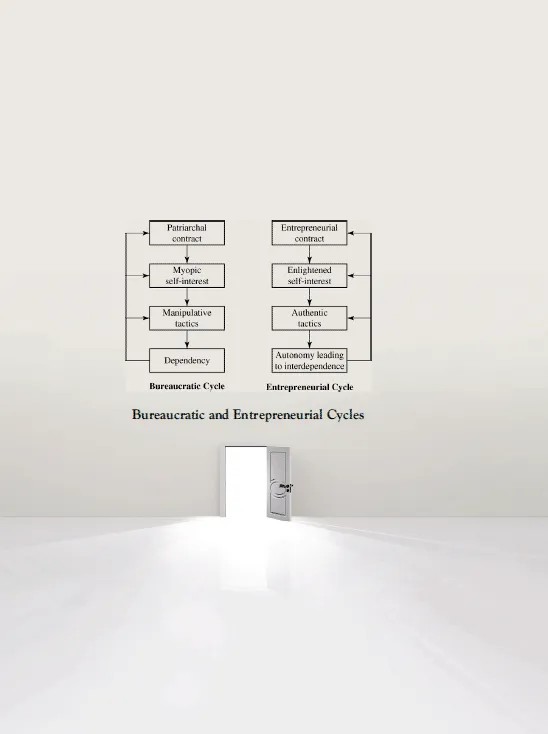

The breeding ground for organizational politics as we know it is the patriarchal mind-set that pervades life in our workplaces. The essence of a patriarchal way of doing business is the choice for safety, predictability, and control. In our search for positive political acts we are forced to confront those forces in the organization that support patriarchy and make the internal entrepreneur a rare species.

This book offers an antidote to the patriarchal mentality that is bred in organizations. Patriarchy is a state of mind and exists regardless of the size of the organization or the level at which you work. The core of this mind-set is to believe the world and its people are fundamentally chaotic and self-centered and therefore have to be contained and directed. This wears the badge of strong and tough-minded leadership. It is also a belief that whenever there is a bump in the road, other people are the problem. Patriarchal beliefs are elusive because we always think they characterize someone else, never ourselves. Thus, efforts to improve our organization too often involve discussion of people outside the room we are in at the moment.

This attitude that it is not my fault is the essence of disempowerment. The alternative to this attitude is the entrepreneur. Most organizations were begun by someone who was willing to bet the farm, but as an organization grows and succeeds, it also creates the conditions for its own destruction. The need for bigness, structure, economy of scale, coordination, and fire-the-founder all work against the spirit of risk and responsibility that breathed life into the firm in the first place.

Reawakening the original spirit of creating something meaningful means we have to confront the issue of our own agency or independence. To pursue autonomy in the midst of a dependency-creating culture is an entrepreneurial act. This book is, in fact, written for those who think of themselves as being in the middle and who wish to create a culture and workplace of their own choosing.

Part One outlines how the patriarchal mind-set has come to drive most organizations and introduces ways of creating an environment and culture that support empowerment. It describes what drives us toward a bureaucratic, negatively political journey and outlines what the alternative, the more entrepreneurial and positive path, would be. Part Two discusses what we as individuals can do to reduce our feeling of futility and make our workplace an expression of our deepest values.

Two

Personal Choices That Shape the Work Environment

In being political we walk the tightrope between advocating our own position and yet not increasing resistance against us by our actions. The path we take is a mixture of two forces: (1) the individual choices we make in creating our environment and (2) the nature of the norms and culture of the organization in which we find ourselves imbedded.

As managers, in addition to delivering organizational outcomes, our fundamental purpose is to build a department and organization that we are proud of. Our unit in many ways becomes a living monument to our deepest beliefs in what is possible at work. We strive to create both a high-performing unit and one that treats its own members and its customers well. Each time we act as a living example of how we want the whole organization to operate, it is a positive political act.

Organizations have limited resources, limited budgets, limited people, and a limited number of actions they can attempt. We want at least our fair share of those resources. Therefore, the methods we use in reaching for those resources are at the heart of politics.

The Road Most Traveled

If we get what we want but do it in a way that is expedient and safe, we are in a quandary. We have achieved our short-term goal but acted in a way that is not an example of the world we want to live in. This dilemma became very vivid to me in a lunch meeting I had with Phil, the president of a major chemicals company.

We had talked at length about his vision of greatness, the human values he wished to see expressed in his organization, and the fact that those values were not a dominant part of the culture of his company. He had discussed the difficulties he had with his boss and how careful the president had to be around his boss, who was chairman of the company. Phil also talked about his wish to become chairman some day and his doubts that this would happen. After listening to him talk about these very personal matters, I asked him why he was even having this conversation with me, a relative stranger who would be deemed rather softheaded in his circles. His company was making record profits; as president, he was sitting on top ...