- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Clinical Anaesthesia

About this book

Clinical Anaesthesia Lecture Notes provides a comprehensive introduction to the modern principles and practices of anaesthesia for medical students, trainee doctors, anaesthetic nurses and other health professionals working with anaesthetists. This fifth edition has been fully updated to reflect changes in clinical practice, guidelines, equipment and drugs.

Key features include:

- A new chapter on the roles of the anaesthetist

- Increased coverage of the peri-operative management of the overweight and obese patient, as well as an introduction to the fundamental aspects of paediatric anaesthesia

- Coverage of recent developments within the specialty, including the rapidly growing recognition of the importance of non-technical skills (NTS), and the management of some of the most common peri-operative medical emergencies

- Links to further online resources

- A companion website at www.lecturenoteseries.com/anaesthesia featuring interactive true/false questions, SAQs, and a list of further reading and resources

Full-colour diagrams, photographs, as well as learning objectives at the start of each chapter, support easy understanding of the knowledge and skills of anaesthesia, allowing confident transfer of information into clinical practice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Clinical Anaesthesia by Matthew Gwinnutt,Carl L. Gwinnutt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Nursing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

An introduction to anaesthesia

General anaesthesia

Nitrous oxide was first synthesized by Joseph Priestley in 1772, and had been known to have analgesic properties since the turn of the nineteenth century, but it was mostly used as a recreational drug (laughing gas). Horace Wells, a dentist in Connecticut, USA, noticed that an assistant under the influence of the gas suffered a significant injury to his shin, but appeared unaware until later. Wells subsequently had one of his wisdom teeth extracted painlessly whilst inhaling nitrous oxide and went on to use the gas in his own practice in 1844. Unfortunately, in 1845, when invited to demonstrate the effects on a patient having a dental extraction at Harvard Medical School, the patient complained of pain and Wells was denounced as a fraud. These early administrations of nitrous oxide carried the risk of severe hypoxia as it was given in close to 100% concentration to obtain an adequate effect. This was solved in the late 1860s, when it was supplied in cylinders under pressure and given in conjunction with 20% oxygen, which lead to an increase in its use.

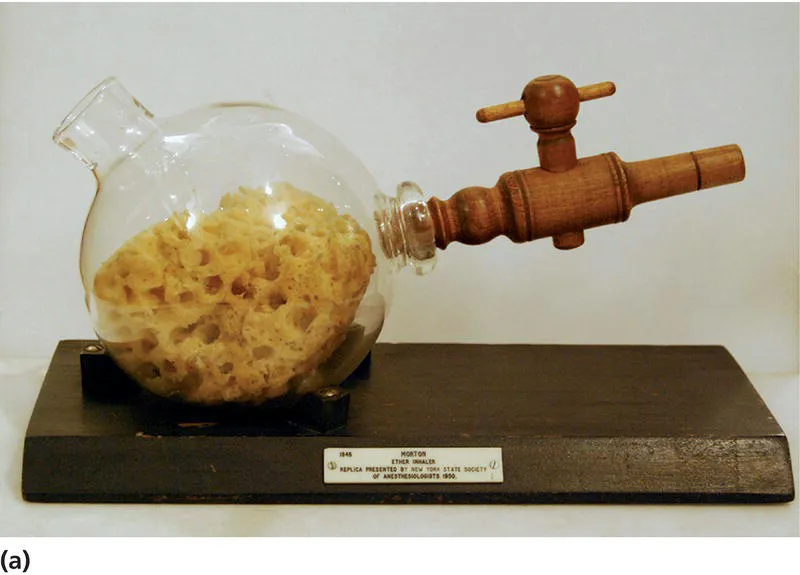

The first successful public demonstration of painless surgery occurred on 16 October 1846 at Massachusetts General Hospital. William Thomas Green Morton, a dentist, presided over the inhalation of ether vapour (diethyl ether, (C2H5)2O) by Edward Abbott while John Warren, the senior surgeon, removed a tumour from Abbott’s jaw. It wasn’t until a few weeks later that a name for the state induced was proposed by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Professor of Anatomy and Physiology at Harvard University: ‘anaesthesia’, from the Greek an (without) and aisthesis (sensation). Compare the simple device used by Morton (Figure 1.1a) with one of today’s anaesthesia machines (Figure 1.1b).

Figure 1.1 (a) Replica of the ether inhaler used by William Morton to give the first public demonstration of general anaesthesia, 16 October 1846, in Massachusetts General Hospital.

Reproduced with kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. (b) Modern integrated anaesthesia system.

Unsurprisingly, news of this discovery spread rapidly and on 19 December 1846, Dr Francis Boott, a physician in London, encouraged James Robinson, a dentist, to give ether to a patient for the extraction of a wisdom tooth. The result was so impressive that Dr Boott persuaded Robert Liston, Professor of Surgery at the University of London, to allow ether to be given during the amputation of Frederick Churchill’s leg, which proved to be a complete success.

Despite the spreading popularity of ether anaesthesia, it was acknowledged that there were problems controlling the dose as the liquid cooled as it vaporized. The first person to apply scientific methodology to giving ether vapour was John Snow, a London physician who invented several pieces of equipment to allow the delivery of known concentrations. He subsequently used chloroform in preference to ether, and in April 1853 successfully gave chloroform to Queen Victoria during the birth of her eighth child, Leopold. He repeated this process in April 1857 at the birth of Victoria’s last child, Beatrice. By the end of the nineteenth century, combinations of nitrous oxide, ether and chloroform, with oxygen, were being used widely to achieve anaesthesia.

Over the next 50 years a number of other inhaled anaesthetics were introduced, including ethyl chloride, cyclopropane and trichloroethylene but ether, chloroform and nitrous oxide dominated. The next major breakthrough came when in 1951 Charles Suckling, working at Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) in Manchester, synthesized halothane and in 1956 it was first used clinically by Michael Johnstone at the Manchester Royal Infirmary. This was the start of the modern era of inhaled anaesthetics and the next 40 years saw the synthesis of several complex halogenated ethers, which yielded the drugs in use today: isoflurane, sevoflurane and desflurane.

The other key discovery that revolutionized general anaesthesia was of neuromuscular blocking drugs or ‘muscle relaxants’. Amazonian Indians were known to apply a plant extract called curare to the tips of their arrowheads that left their prey paralysed. In 1812, it was shown that artificial ventilation could keep animals alive until the poison wore off and they made a full recovery. The science behind this observation was revealed in 1850 by the French physiologist Claude Bernard when he showed that curare acted at the neuromuscular junction. In 1900, the anti‐curare effects of physostigmine were described and so the effects of curare could be reversed when needed, rather than waiting for spontaneous recovery. Interestingly, the first clinical use of curare was not in anaesthesia, but in the treatment of tetanus in 1934. It was not until 1942 that Harold Griffith and Enid Johnson at Magill University, Montreal, used curare as part of their anaesthetic for a patient undergoing an appendicectomy. Curare (d‐tubocurarine) was first introduced into clinical practice in England by Gray and Halton in Liverpool in 1946. Five years later suxamethonium (succinylcholine) was introduced into clinical practice, again after a considerable delay since its first description in 1906. In 1966, pancuronium, the first synthetic muscle relaxant, was introduced, followed in the early 1980s by vecuronium and atracurium.

Finally, no writing on the history of general anaesthesia is complete without a brief mention of tracheal intubation. This evolved from the use of metal tubes in the eighteenth century which were passed into the trachea to aid with resuscitation. It was William MacEwen, a Glasgow surgeon, who deliberately first introduced a flexible metallic tube into a patient’s trachea through which chloroform in air was given. The patient required the removal of a tumour at the base of their tongue and would otherwise have needed a tracheostomy. Numerous similar techniques followed, but it was Magill and Rowbotham who first passed tubes into the trachea to secure the airway and allow unhindered access to the face and airway to perform reconstructive surgery. The endotracheal tubes that Magill went on to develop were reusable, made from rubber, and became the universal standard for over 40 years. They have now been replaced by single‐use tubes made from polyvinyl chloride (PVC).

Local and regional anaesthesia

The Indians in Bolivia and Peru had chewed the leaves of the bush Erythroxylum coca for its stimulant properties which enabled them to go on prolonged hunting trips without tiring. In the mid‐1850s, the active ingredient, an alkaloid named cocaine, had been extracted and was investigated by Freud as a remedy for morphine addiction and use in psychoneurotic patients. Aware of the effects of cocaine in ‘deadening’ mucous membranes, he asked a colleague, Carl Koller, an eye surgeon in Vienna, to carry out some investigations. Koller experimented firstly on animals, then himself and friends and finally on patients. He showed that instilling cocaine into the conjunctival sac made eye operations completely painless for the first time. By the 1890s, cocaine was being used for nerve and plexus blocks, but many of the pioneers were unaware of its addictive properties and experimented upon themselves, becoming addicts in the process. This problem lead to the development of safer alternatives and by the turn of the twentieth century, stovaine and procaine (novocaine) were widely used. Lignocaine (lidocaine) was synthesized in 1943 and first used clinically in 1948 and bupivacaine appeared in 1963.

The development of central neural blockade or spinal anaesthesia came about by accident in 1885. James Corning, a New York neurologist, accidentally injected cocaine intrathecally in a dog and, noting its profound effect, repeated the injection in a patient. He coined the term ‘spinal anaesthesia’, suggesting it might have a use for surgery. In 1898, August Bier, a German surgeon, gave the first deliberate spinal anaesthetic for surgery with cocaine. Having repeated the technique successfully on a further small group of patients, Bier allowed his assistant to give intrathecal cocaine to him, thereby proving his faith in the technique. The introduction of stovaine and procaine eliminated the risk of toxicity and addiction, and the popularity of spinal anaesthesia spread.

Epidural anaesthesia soon followed, firstly using a technique of giving the drugs via the caudal route. The lumbar route, which is widely used today, was popularized in Europe in the 1930s by the Italian surgeon Achille Dogliotti and in the UK in the 1940s by Charles Massey Dawkins. Shortly after, the first use of a catheter in the epidural space to allow continual analgesia was described.

Anaesthesia today

Anaesthesia has progressed from the early days of dripping ether or chloroform onto a piece of gauze held over the patient’s face. Lack of control and the use of relatively toxic drugs meant that effects were often unpredictable and complications, including death, were not uncommon. Monitoring the patient meant feeling their pulse, looking at their colour and observing rate and depth of breathing. Training was done ‘on the job’ and there were no standards or regulations.

Currently in the United Kingdom, doctors who have completed their medical training then undergo a further seven years training to become anaesthetists. During this time, they take part in a structured training programme and sit postgraduate examinations to become a Fellow of the Royal College of Anaesthetists (FRCA) [1.1]. In addition, many also undertake additional subspecialization training, for example in critical care, pain management, cardiothoracic, neurosurgical or paediatric anaesthesia. Anaesthetists...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- About the companion website

- 1 An introduction to anaesthesia

- 2 Anaesthetic assessment and preparation for surgery

- 3 Anaesthetic equipment and monitoring

- 4 Drugs and fluids used during anaesthesia

- 5 The practice of general anaesthesia

- 6 Local and regional anaesthesia

- 7 Specialized areas of anaesthesia

- 8 Recovery from anaesthesia

- 9 Perioperative medical emergencies

- Index

- The Lecture Notes series

- End User License Agreement