- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cardiovascular Hemodynamics for the Clinician

About this book

Cardiovascular Hemodynamics for the Clinician, 2nd Edition, provides a useful, succinct and understandable guide to the practical application of hemodynamics in clinical medicine for all trainees and clinicians in the field.

- Concise handbook to help both practicing and prospective clinicians better understand and interpret the hemodynamic data used to make specific diagnoses and monitor ongoing therapy

- Numerous pressure tracings throughout the book reinforce the text by demonstrating what will be seen in daily practice

- Topics include coronary artery disease; cardiomyopathies; valvular heart disease; arrhythmias; hemodynamic support devices and pericardial disease

- New chapters on TAVR, ventricular assist devices, and pulmonic valve disease, expanded coverage of pulmonary hypertension, fractional flow reserve, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and valvular heart disease

- Provides a basic overview of circulatory physiology and cardiac function followed by detailed discussion of pathophysiological changes in various disease states

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cardiovascular Hemodynamics for the Clinician by George A. Stouffer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Cardiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Basics of hemodynamics

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to basic hemodynamic principles

James E. Faber and George A. Stouffer

Hemodynamics is concerned with the mechanical and physiologic properties controlling blood pressure and flow through the body. A full discussion of hemodynamic principles is beyond the scope of this book. In this chapter, we present an overview of basic principles that are helpful in understanding hemodynamics.

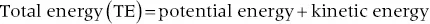

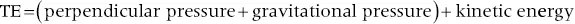

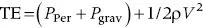

1. Energy in the blood stream exists in three interchangeable forms: pressure arising from cardiac output and vascular resistance, “hydrostatic” pressure from gravitational forces, and kinetic energy of blood flow

Daniel Bernoulli was a physician and mathematician who lived in the eighteenth century. He had wide‐ranging scientific interests and won the Grand Prize of the Paris Academy 10 times for advances in areas ranging from astronomy to physics. One of his insights was that the energy of an ideal fluid (a hypothetical concept referring to a fluid that is not subject to viscous or frictional energy losses) in a straight tube can exist in three interchangeable forms: perpendicular pressure (force exerted on the walls of the tube perpendicular to flow; a form of potential energy), kinetic energy of the flowing fluid, and pressure due to gravitational forces. Perpendicular pressure is transferred to the blood and vessel wall by cardiac pump function and vascular elasticity and is a function of cardiac output and vascular resistance.

where V is velocity and ρ is density of blood (approximately 1060 kg/m3)

where g is gravitational constant and h is height of fluid above the point of interest.

Although blood is not an “ideal fluid” (in the Newtonian sense), Bernoulli’s insight is helpful. Blood pressure is the summation of three components: lateral pressure, gravitational forces, and kinetic energy (also known as the impact pressure or the pressure required to cause flow to stop). Pressure is the force applied per unit area of a surface. In blood vessels or in the heart, the transmural pressure (i.e., pressure across the vessel wall or ventricular chamber wall) is equal to the intravascular pressure minus the pressure outside the vessel. The intravascular pressure is responsible for transmural pressure (i.e., vessel distention) and for longitudinal transport of blood through the vessels.

Gravitational forces are important in a standing person. Arterial pressure in the foot will exceed thoracic aortic pressure due to gravitational pull on a column of blood. Likewise, arterial pressure in the head will be less than thoracic aortic pressure. Similarly, gravitational forces are important in the venous system, since blood will pool in the legs when an individual is standing. Decreased ventricular filling pressure results in a lower cardiac output and explains why a person will feel lightheaded if rising abruptly from a sitting or supine position. In contrast, gravity has negligible effect on arterial or venous pressure when a person is lying flat. Gravitational pressure equals the height of a column of blood × the gravitational constant × the fluid density. To calculate hydrostatic pressure at the bedside (in mm Hg), measure the distance in millimeters between the points of interest, for example heart and foot, and divide by 13 (mercury is 13 times denser than water).

Kinetic energy is greatest in the ascending aorta where velocity is highest, but even there it contributes less than 5 mm Hg of equivalent pressure.

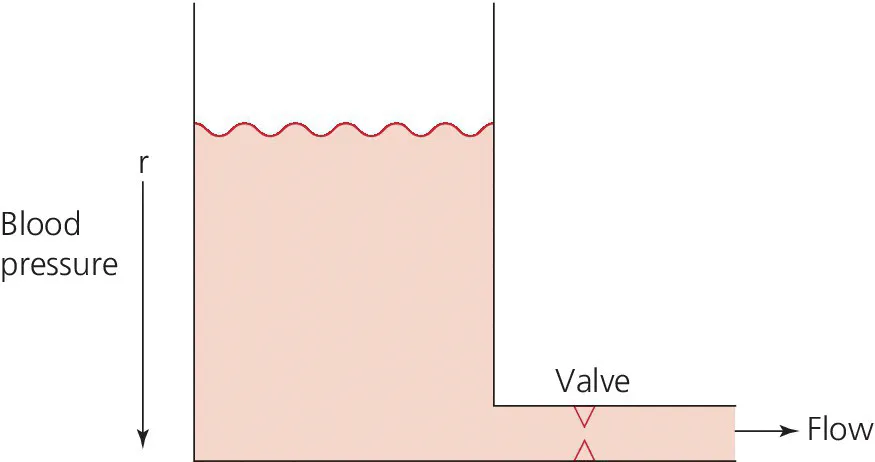

2. Blood flow is a function of pressure gradient and resistance

One of the properties of a fluid (or gas) is that it will flow from a region of higher pressure (e.g., the left ventricle) toward a region of lower pressure (e.g., the right atrium; Figure 1.1). In clinical practice, the patient is assumed to be supine (negating the gravitational component of pressure) and at rest. As already mentioned, kinetic energy is negligible compared to blood pressure at normal cardiac output and thus blood flow is estimated using the pressure gradient and resistance.

Figure 1.1 A simple hydraulic system demonstrating fluid flow from a high‐pressure reservoir to a low‐pressure reservoir. Note that the volume of flow can be affected by a focal resistance (i.e., the valve).

The primary parameter used in clinical medicine to describe blood flow through the systemic circulation is cardiac output, which is the total volume of blood pumped by the ventricle per minute (generally expressed in L/min). Cardiac output is equal to the total volume of blood ejected into the aorta from the left ventricle (LV) per cardiac cycle (i.e., stroke volume) multiplied by the heart rate. This formula is important experimentally, but of limited used clinically because stroke volume is difficult to measure. Cardiac output is generally measured using the Fick equation or via thermodilution techniques, which are discussed in Chapter 6.

To compare cardiac output among individuals of different sizes, the cardiac index (c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- List of contributors

- PART I: Basics of hemodynamics

- PART II: Valvular heart disease

- PART III: Cardiomyopathies

- PART IV: Pericardial disease

- PART V: Hemodynamic support

- PART VI: Coronary hemodynamics

- PART VII: Miscellaneous

- Index

- End User License Agreement