Project management theory, and to some extent practice, have tended to focus on process, systems and documents. But projects are instigated, designed and delivered by human beings. This book focuses on the people involved in projects. It conceptualises the project as a social network, or more accurately, multiple layers of social networks, each network dedicated to the delivery of a particular project function. One of the exciting discoveries during the research that this book draws upon was the importance of self‐organising project networks, particularly in complex projects. In this book, I explore some of the factors that affect the behaviour of individuals as project actors, including game theory and personality type. I also consider the environmental and personal attributes that might enable networks to function more effectively, particularly in the context of the project. I look at Building Information Modelling (BIM), because there is an important link between the efforts being made in relation to BIM, and social networks. Finally, the book presents some case study material related to a two‐year research project which I led involving the Centre for Organisational Network Analysis and Transport for London.

The previous book in this series – Social Network Analysis in Construction (Pryke, 2012) – presented social network analysis (SNA) as an innovative method for the analysis of project organisations. It rationalised the SNA approach, looked at the importance of collaborative relationships in project organisations and proposed a theoretical framework to support the conceptualisation of the project as a network of relationships – contracts, information flows and financial incentives. The book proposed a model for the use of SNA which others might adopt in their research and presented four case studies, comparing collaborative, relationship‐based procurement and traditional strategies for procurement. The book provided an insight into the interpretation of network data derived from project‐based organisations and finally took a somewhat speculative look at how networks might be managed.

It was the chapter on managing networks that was in my view the most innovative, and Managing Networks aims to develop that theme using case study material gathered from recent research carried out at the Centre for Organisational Network Analysis at University College London (CONA@UCL). The raison d’être of CONA is to explore the void that is evident between procurement, systems and organisational hierarchies.

In our projects, we set about procuring resources, place those resources in structures that are often expressed either hierarchically or to a high level of abstraction, and then try to manage the self‐organising networks of human relationships that evolve, without conceptualising those relationships as networks. It is little wonder that we often find it difficult to analyse why some projects seem to be successful and others less so. A small group of those associated with CONA@UCL set about trying to classify, and to some extent quantify, organisationally, the ‘good’ projects and the ‘bad’ projects, using the language of the social network analysts. Examples of this work are: Badi and Pryke (2006), Badi et al. (2014), Badi et al. (2016a and 2016b), Doloi et al. (2016), Pryke et al. (2017), Pryke et al. (2015a and 2015b), Pryke (2014), Pryke et al. (2014), Pryke et al. (2013), Pryke and Badi (2013), Shepherd and Pryke (2014), El‐Sheikh and Pryke (2010), Pryke (2005a and 2005b), Pryke and Pearson (2006).

So, this book aims to respond to the needs of several groups: those who ask what the social network theory of project organisations is; the practitioners who ask ‘how can I use social network analysis to run smarter projects’; the students who ask how we can start teaching project management in a way that helps them to identify network and actor characteristics – to classify project coalition activity and the actors involved in network terms and to start to build toward defining management in a project‐based environment in network terms.

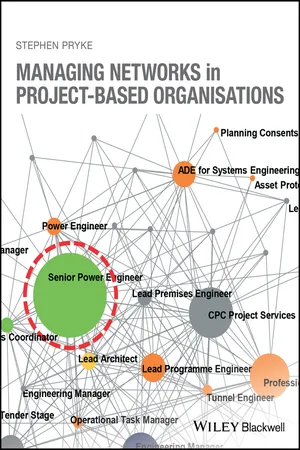

The analysis and representation or visualisation of project‐focused activity has involved task‐dependency‐based approaches, structural analysis (hierarchical) and process mapping, all of which fail to reflect the relationships that deliver our projects – relationships that we can classify by project function.

Structure of the Book

Chapter 2: Theoretical Context This chapter locates the concept of managing networks within a context of managing projects and their supply chains. A number of assumptions have been made about the nature of projects around which procurement and project management practices have evolved. I argue in Chapter 2 that our choice of procurement and the subsequent project management strategies applied have not kept pace with the complexity of many projects. It is also argued that at the point where procurement is completed (and resources identified and secured) a transition occurs where those resources have to configure themselves into systems that will deliver a successful project. We know little of how these self‐organising systems evolve. Our lack of awareness means that we typically do not facilitate or manage these systems.

The chapter reflects on the vestiges of scientific management that still remain in project management research and practice. The fact that our projects are delivered by unpredictable, sometimes irrational, imperfect human beings seems sometimes to be ignored in our discussion about programming, risk management and the whole range of sub‐systems that we typically bring together in project management. The chapter concludes by pointing to the fact that our highly‐connected lives no longer rely on distinguishing task and social structure. Human beings essentially get things done through links to other human project actors. The idea that everything that does not constitute a formal direction or instruction under the terms of the contract should be classified as ‘informal’ is firmly rejected. There has, perhaps, been some confusion between informal and recreational ties. Although recreational ties are undoubtedly fascinating and important, this book does not deal with them.

The chapter provides a context and perhaps rationale for the chapters that follow. The key themes are developed in more depth in these subsequent chapters.

Chapter 3: Networks and Projects This chapter starts with the reflection that the last fifty years have brought only modest progress in our understanding of ‘systems… functions…interrelationships, and the location and prominence of…control and coordination centres’ (Higgin and Jessop, 1965: 56). In fact many of the techniques that we use to manage projects seem to ignore all of these issues. The chapter makes a start on the formulation of sub‐systems that might be studied to enable a better understanding of how projects are really managed. The concepts of ritualistic behaviour and routines are introduced and I reflect on the fact that individuals are attracted to routines because they provide consistency and stability, and reduce mental effort (Becker, 2004).

This chapter refers to Morris’ (2013) discussions about the maturity of project definition, or more accurately the tendency for project definition frequently to be insufficiently mature at the point of transition between pre‐ and post‐contract stages. The idea that this uncertainty, exacerbated by continually increasing complexity, leads to project actors forming networks to secure information, solve problems and disseminate processed information is introduced and rationalised. It is argued that at the transition from resource procurement to project delivery, routines are not adequate in the face of complexity in both task and structure. I ask the reader to move on from discussions about the ‘iron triangle’ for the reasons that: it is very difficult to define client needs at a stage early enough to use procurement successfully; it is difficult to avoid agency problems in procurement and delivery; and, arguably, change in project definition improves value to client and end‐users, rather than the reverse. It is not possible to allocate project and supply chain roles accurately and to maintain these roles as a constant throughout the entire project design and delivery period. Project systems are iterative and transient and this is to a great extent not reflected in the contractual relationships established through many procurement approaches.

The chapter provides an introduction to project actor characteristics (drawn from Pryke, 2012), and an overview is given of network characteristics (path lengths and density) and linkage characteristics (tie strength or value and direction). The chapter ends with a reflection on the question posed – why networks? – and makes a link to Chapter 4. The chapter concludes that the identification and analysis of interaction networks between the individuals engaged to deliver a project is the only way to observe the self‐organising, complex project function‐related networks that hold the key to understanding successful and unsuccessful project delivery. If we can understand and map these networks, we can define the actor roles and network configurations that constitute successful project delivery and begin to replicate and eventually to manage these networks.

Chapter 4: Why Networks? The chapter starts with some discussion about the origins of SNA and references to Nohria and Eccles’ (1992) work on rationalising the use of SNA in organisations. I emphasise that in a project environment it is important to distinguish between the two types of actors: individuals and firms. Contracts are established between firms and projects are delivered through relationships between individuals. I discuss some of the issues to be considered when applying SNA to project and supply chain research – the quantitative/interpretative paradigm; the issue of causality and the complexity of SNA as an analytical approach; the importance of precise network classification; and the limitations arising from sampling. Studying and managing projects that are highly complex in terms of technical content, as well as process, inevitably leads to complexity in both analysis and management approaches.

Some basic SNA terminology is discussed as a preamble to the analysis and discussion in later chapters. A structure for the analysis of projects (and in particular construction and engineering projects) is introduced. I suggest that while traditional project management analytical tools and management approaches essentially pursue the ‘iron triangle’ of cost, time and quality, clients’ and stakeholders’ needs are sophisticated and complex, requiring a more finely‐grained approach to both analysis and management.

I end this chapter with a call for more research using SNA in projects and provide some details about suitable software and the identification of network boundaries for research.

Chapter 5: Self‐Organising Networks in Projects In this chapter I further develop the theme that procurement and project management strategies have not kept pace with rapidly increasing complexity in projects. I discuss the increased prevalence of temporary, project‐related organisation forms in a range of industries. Film and software tend to be highly creative but construction and engineering are perceived to be more routine‐based. Yet this is contentious and many involved in major construction and engineering projects would emphasise the need for creativity in finding design solutions and in problem‐solving. The chapter considers what clients want from projects and although many clients may not express it in those terms, ‘completeness’ is felt to be of primary concern to most clients. I assert that the previous focus on the iron triangle in the context of financial incentive for designers and constructors is dysfunctional in terms of the client’s needs and leads to ritualistic behaviour by project actors. In this context, the chapter moves on to focus upon what I refer to as some ‘dangerous assumptions’.

These dangerous assumptions move in chronological order through project procurement and delivery, starting with the definition of client needs. The definition of clients’ needs, the difficulty of achieving an accurate representation of those needs in documentary form by human or technological means, the fact that changes in project definition have be...