![]()

SECTION Three

Risk Management Applications

![]()

CHAPTER 12

Credit Risk Management

The effective management of credit risk is a challenge faced by all companies, and a critical success factor for financial institutions and energy firms faced with significant credit exposures. Most obviously, banking institutions face the risk that institutional and individual borrowers may default on loans. Banks must therefore underwrite and price each loan according to its credit risk and ensure that the overall portfolio of loans is well diversified.

However, both financial and non-financial institutions also face credit risk exposures besides the default risk associated with lending activities. For example, the sellers of goods and services face credit risk embedded in their accounts receivable. Investors may see significant decreases in the value of debt instruments held in their portfolios as a result of default or credit deterioration. Sellers and buyers of capital markets products will only get paid on any profitable transaction if their counterparties fulfill their obligations to them. Furthermore, the increasing mutual dependence involved under arrangements such as outsourcing and strategic alliances exposes companies to the credit condition of their business partners.

Given this multiplicity of phenomena, there is obviously a need for a clear definition of credit risk. Credit risk can be defined as the economic loss suffered due to the default of a borrower or counterparty. Default does not necessarily mean the legal bankruptcy of the other party, but merely failure to fulfill its contractual obligations in a timely manner, due to inability or unwillingness.

A consultative paper issued in 1999 by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision recognized that “the major cause of serious banking problems continues to be directly related to lax credit standards for borrowers and counterparties, poor portfolio risk management, or a lack of attention to changes in economic or other circumstances that can lead to a deterioration in the credit standing of a bank's counterparties.”1 While this quote focuses specifically on the banking industry, the need to establish sound credit risk management practices for customer receivables, investment activities, and counterparty and business partner exposures is relevant to any given industry.

Credit risk management deals with the identification, quantification, monitoring, controlling, and management of credit risk at both the transaction and portfolio levels. Although the level and volatility of future losses are inherently uncertain, statistical analyses and models can help the risk manager quantify potential losses as input to underwriting, pricing, and portfolio decisions. Before we can do this, however, we will need to define some key concepts in credit risk management.

KEY CREDIT RISK CONCEPTS

Exposure, Severity, and Default

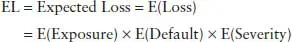

The credit loss on any transaction, whether a straightforward loan or complex swap, can always be described as the product of three terms:

Loss is the actual economic loss to the organization as a result of the default or downgrade of a borrower or counterparty—that is, as a result of a credit event. Exposure is the loan amount, or the market value of securities that the organization is due to receive from the counterparty at the time of the credit event.2 This is the amount at risk. Default is a random variable which is either one (if the transaction is in default) or zero in the context of a single borrower or counterparty, but it may also represent the overall default rate of a portfolio. Severity is the fraction of the total exposure that is actually lost—the severity of a loss can be reduced by debt covenants, netting and collateral arrangements, and downgrade provisions.

Expected Loss

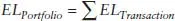

Another key concept is expected loss (EL), which represents the anticipated average rate of loss that an organization should expect to suffer on its credit risk portfolio over time. This is effectively a cost of doing business, and should thus be reflected directly in transaction pricing. The expected value of credit losses is equal to the product of the expected values of each of its components:

E(Exposure) is the expected exposure at the time of the credit event; it depends strongly on the type of transaction and on the occurrence of future random events. For loans, exposure is usually just the amount of the loan. Where a trading exposure to a counterparty is involved, the expected exposure must usually be modeled. For example, it is usually necessary to use a simulation model in order to find the expected exposures of long-dated transactions such as swaps or forwards.

E(Default) is the expected default frequency and reflects the underlying credit risks of the particular borrower or counterparty. It can either be estimated from the borrower's or counterparty's public debt rating or by calibrating the organization's own credit-grading scale. While each individual transaction is obviously either performing or in default—there is little middle ground between the two states—there is an expected frequency of default within an overall portfolio.

E(Severity) is the expected loss in the event of default. It is a function of facility type, seniority, and collateral. The severity is equal to the lost principal and interest, together with the cost of administering the impaired facility; it is expressed as a percentage of the exposure at the point of default. Since there is insufficient public data on recovery rates, and these tend to vary with the type of transaction, they must usually be estimated from the organization's own recovery data. Recovery rates for publicly traded bonds can be obtained from the major rating agencies.

The EL for a portfolio is simply the sum of the ELs of the individual transactions:

Unexpected Loss

Unexpected loss (UL) is a more important measure of risk than expected loss. EL is, as the name suggests, a reasonably predictable average rate of loss. Organizations do not have to hold capital against expected loss, assuming that they have priced it into the relevant transaction(s) correctly and have established the appropriate credit reserves. On the other hand, unexpected loss represents the volatility of actual losses that will occur around the expected level. It is the existence of UL that creates the need for a capital cushion to safeguard the viability of the organization if losses turn out to be unexpectedly high.

Statistically speaking, UL is defined as the standard deviation of credit losses. It is derived, mathematically speaking, from the components of EL:

If all transactions were to default at the same time, we would simply add up the UL of individual transactions to determine the overall UL of a portfolio. However, this is obviously extremely unlikely to happen, unless there are common factors driving the credit performance of all the transactions in the portfolio.

It's improbable, for example, that individual borrowers from different geographical locations would all default on their credit card debts at exactly the same time, although changes in the national levels of interest rates would likely be an important common factor. Similarly, a shared geographical location or industrial sector is likely to be important common factors for corporate borrowers.

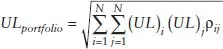

The degree to which individual default behaviors are related is known as the default correlation. Broadly speaking, the more diverse (less correlated) the transactions in the portfolio are, the less likely it is that many of them will suffer a credit event simultaneously. Hence, the unexpected loss on a portfolio is dependent on its level of diversification as well as on the unexpected losses associated with individual transactions. This is measured in terms of the default correlations among transactions. Thanks to diversification, the unexpected loss on a portfolio will be less than the sum of the unexpected losses of its component transactions. In fact, it is:

where (UL)i is the unexpected loss on the ith transaction in the portfolio and ρij is the default correlation between the ith & jth transactions in the portfolio. The higher the correlation between a new transaction and the portfolio, the more risk it adds to the portfolio. One of the key objectives for a risk manager is, therefore, to ensure that portfolios are sufficiently diversified—thus reducing the unexpected loss on the portfolio—by ensuring that credit exposures are not overly concentrated in any obligor, industry, country, or economic sector.

A word of caution on default correlation—as with general asset price correlations, default correlations increase significantly during market crises. As such, the benefit of credit portfolio diversification may not be realized during periods when it is most needed. Risk managers should stress test correlation assumptions (i.e., setting them at or near historical highs) to measure the sensitivity of UL to various levels of default correlation.

Reserves and Economic Capital

A credit loss reserve represents the amount set aside for expected losses from the firm's total portfolio of credit exposures. For example, bad-debt provisions might be made to cover anticipated losses over the life of a loan portfolio. A reserve is a specific element of the balance sheet, while provisions and actual losses are treated as income statement items.

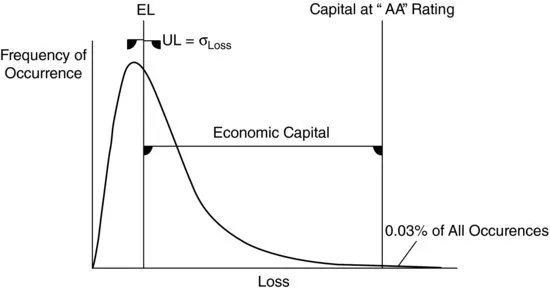

A firm must also earmark some capital to guard against large unexpected losses, however. This capital is known as economic capital, which is the amount that is required to support the risk of large unexpected losses. The amount of economic capital3 required is determined from the credit loss distribution, which we will describe below.

Economic capital is an important concept for equity holders as well as debt holders. For equity-holders, economic capital can be used as a yardstick against which returns from different risk-taking activities can be consistently measured. For debt-holders, the economic capital can be viewed as the capital cushion against unexpected loss that is required to maintain a certain debt rating. It is determined in a similar way to the solvency tests applied by rating agencies, such as Standard & Poor's (S&P) or Moody's Investors Service, when assigning credit ratings.

For example, firms rated AA by S&P default with a 0.03 percent frequency over a one-year horizon. If a firm has a AA target-solvency standard, its economic capital can then be determined as the level of capital required to keep the firm solvent over a one-year period with 99.97 percent confidence. Since this is a probabilistic quantity, it will depend on the distribution of credit losses (see Figure 12.1).

Credit loss distributions are skewed because credit losses can never be less than zero. That would imply that borrowers pay back more than they owe when conditions are better than expected, which clearly does not happen.4 In most economic environments, one would expect relatively low levels of losses (at any competent institution, anyway). However, when times are worse than expected—for example, a recession causes a high level of defaults—credit losses can be much higher than average, and thus generate a longer, skewed tail. The distribution is leptokurtic, that is, the probability of large losses occurring is greater for a given mean and standard deviation than would be the case if the distribution was normal.

The loss distribution can be estimated by:

- Assuming that it conforms to one of the standard textbook distributions, such as the beta or gamma distribution, and parameterizing the distribution to match the portfolio's mean and standard deviation

- Analyzing publicly available information for peer firms, that is, their capital relative to their historical loss volatility (this requires some simplifying assumptions)

- Using numerical techniques or simulation to estimate and aggregate the yearly loss level of the portfolio over many business cycles.

Once the UL has been calculated and the loss distribution estimated, the desired debt rating (or target solvency standard) has to be factored into the economic capital calculation. This is done by introducing a capital multiplier (CM), which represents the number of multiples of UL required to create a capital cushion sufficient to absorb a loss at the confidence level implied by the institution's credit rating. It is determined from the loss distribution. As mentioned above, an institution that is seeking a AA rating must hold enough economic capital to protect against all losses except those so large that they have less than a 0.03 percent chance of occurring in any given year. Economic capital for credit risk is determined by:

Off-Balance Sheet Credit Risk

When one thinks about credit risk, large loan losses come most immediately to mind. The dramatic and highly publicized credit crises of the last two decades include those ...