eBook - ePub

Couples and Family Therapy in Clinical Practice

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Couples and Family Therapy in Clinical Practice

About this book

Couples and Family Therapy in Clinical Practice has been the psychiatric and mental health clinician's trusted companion for over four decades. This new fifth edition delivers the essential information that clinicians of all disciplines need to provide effective family-centered interventions for couples and families. A practical clinical guide, it helps clinicians integrate family-systems approaches with pharmacotherapies for individual patients and their families. Couples and Family Therapy in Clinical Practice draws on the authors' extensive clinical experience as well as on the scientific literature in the family-systems, psychiatry, psychotherapy, and neuroscience fields.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Couples and Family Therapy in Clinical Practice by Ira D. Glick,Douglas S. Rait,Alison M. Heru,Michael Ascher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychotherapy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION VI

Family Treatment When One Member Has a Psychiatric Disorder or Other Special Problem

We discuss in this section the differences in evaluation and treatment made necessary by the presence of a psychiatric disorder or other special problem in a family member. In Chapter 18, we discuss how the family is affected and how to use family intervention when one member has a psychiatric disorder. In Chapter 19, we examine how treatment techniques must be modified for special but common situations such as the problematic family in which aggressive, abusive, or suicidal behaviors are frequent. In Chapter 20, we go on to discuss how family behavior can be organized around acute or chronic mental illness and why the therapist must be aware of the typical patterns and responses of families in these situations. We also discuss treatment in settings such as the psychiatric hospital or the community mental health center, in which these problems are (or should be) managed from a family perspective. Chapter 21 asks the family therapist to consider how medical and psychiatric illness affect the family and how specific family characteristics influence the course of medical illness. In order to achieve this understanding, the family therapist must expand the traditional family assessment interview to include clarifying questions. Medical illness may cause the family to feel overwhelmed with practical and emotional challenges. In such situations, the family therapist can provide a therapeutic space for family reflection. Regarding specific family interventions, family research demonstrates the effectiveness of family interventions such as family inclusion approaches, family psychoeducation and systemic family therapy.

CHAPTER 18

Family Treatment in the Context of Individual Psychiatric Disorders

Objectives for the Reader

- To be aware of family interaction patterns associated with individual psychiatric disorders

- To know the indications for, and techniques of, family intervention in combination with other treatment methods in specific psychiatric disorders

Introduction

In this chapter, we demonstrate how family, individual, dynamic, and physiological issues intersect in various mental disorders, and how family therapy is conducted when a family member has a specific disorder. We concentrate on those diagnoses in which we believe family issues are most often part of the total picture. We also propose treatment guidelines and strategies for each disorder.

If the identified patient has a specific major psychiatric diagnosis, treatment will usually include individual therapy and, most often, medication. In most instances, treatment is also indicated for the family problems and interactions accompanying these conditions. Some of the family problems may be related to the etiology of the individual illness, some may be secondary to it, others may adversely affect the course of the illness, and still others may not be connected at all. For example, if schizophrenia has developed in a spouse early in the marriage, the therapist's attention must be directed not only to treatment of the mental illness but also to the nature of the marital interaction, including its possible role in exacerbating or ameliorating the illness. If a major psychiatric disorder occurs in one family member, attention must be paid to the family's ability to cope with the illness. For example, a child may respond to his or her mother's severe depressive illness by becoming a caretaker to younger siblings, at risk of his or her own development, or the child may begin “acting out.” The cardinal symptoms of depression like lowered mood, anhedonia and irritability will cause marital stress. Conversely, the depression may have been symptomatic of severe marital or family stress.

Family interventions for many psychiatric disorders are one component of a multimodal prescription, but those interventions may be crucial to success.

The Family Model and Individual Diagnosis

In medicine, psychiatry, and related fields, the traditional focus of healing and treatment has been on disease and disorder. Diagnosis as a rubric implies a model that includes signs and symptoms, etiological theories, treatment, and prognosis. For some family therapists, any kind of labeling of the individual is inappropriate, because it locates the problems in the individual while ignoring the role of family members and other environmental conditions and stimuli. We subscribe to a broad psychosocial model in which the individual and family model interacts.

This chapter will discuss how the existing research informs clinical practice. We will be highlighting many individual disorders but use schizophrenia as a prime example.

Schizophrenia

Rationale

From the early days of the family therapy movement, clinicians have had a fascination with schizophrenia and the families of patients with the disorder. Over the last five decades, the family approach has changed dramatically in this area, relating to these most seriously ill patients and their family interactions.

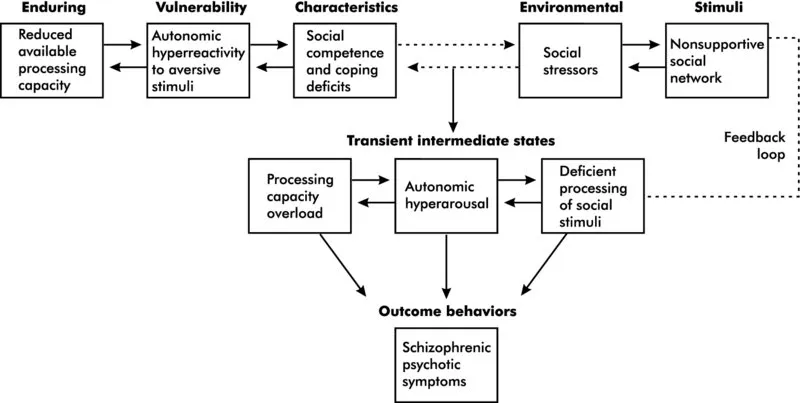

Early family theorists were interested in the family's role in the etiology of schizophrenia. These writers emphasized concepts such as the schizophrenogenic mother (Fromm-Reichman 1948), faulty boundary setting, and family interactions such as double bind (Bateson et al. 1956, 1963), pseudo-mutuality (Wynne et al. 1960), and schism and skew (Fleck 1960). Current conceptualizations have been influenced by subsequent research concerning the multiple factors in the etiology of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is now understood to be a brain disorder with strong familial links. Specific brain area functions show abnormalities. The familial aggregation of persons with schizophrenia appears to be largely from genetic causes (Wahlberg et al. 1997, Swerdlow et al. 2014). Changes in brain function may precede adolescence. A vulnerability-stress model of schizophrenic episodes was proposed in the 1980s (Nuechterlein and Dawson 1984), emphasizing individual deficits (e.g., information-processing deficits, autonomic reactivity anomalies, social competence and coping limitations) in combination with stressors (e.g., life events, family environmental stress, substance abuse as it affects the brain). This model still seems relevant to the development of psychotic episodes (see Figure 18.1).

Figure 18.1 A tentative, interactive vulnerability-stress model for the development of schizophrenic psychotic episodes.

Source: Nuechterlein and Dawson, 1984. Reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press.

A number of historical and scientific trends have contributed to the development of the psychosocial interventions recommended today for families of persons with schizophrenia. One trend is the development of the construct of expressed emotion. In 1962 a team of British investigators reported that patients who returned to live with their families after psychiatric hospitalization were more prone to rehospitalization than those patients who went to boarding homes and hostels after discharge (Brown et al. 1962). To explore these interesting leads, this group developed a semi-structured interview to quantify the family environment to which the patient would return.

This instrument, the Camberwell Family Interview, provides measures of what these researchers have termed expressed emotion, which is primarily an index of the family's criticism of, and overinvolvement with, the identified patient. Although researchers commonly refer to high expressed emotion families, it is important to understand that the rating of expressed emotion is based on observations made of a single cross-sectional interview of one family member and the patient. In subsequent years, it has been found both with British and American samples that the percentage of patients in families with high expressed emotion who relapse, or are rehospitalized, is significantly higher than the percentage in the low expressed emotion families.

The concept of expressed emotion has been dissected further. In the long term (i.e., after the acute episode), emotional overinvolvement is associated with a better social outcome in patients because it is part of the increased care that these disabled patients need (and desire) (King and Dixon 1996). The concept of expressed emotion may be detecting excess stress in the environment of the person with schizophrenia; however, much more needs to be learned about how the patient may contribute to this family response, how expressed emotion changes over time, and how it varies across cultures. Somewhat parenthetically, “expressed emotion” has been found important in understanding and preventing relapse not only in schizophrenia but also in both mood disorders and eating disorders (see later in this chapter) (Butzloff and Hooley 1998).

This work has led to very specific family therapeutic approaches concerning schizophrenia. Influenced by such work, researchers have put together treatment packages with the specific goals of reducing familial hostility and overinvolvement in the acute phase. These studies will not only provide data on a potential intervention strategy but also might provide experimental evidence that expressed emotion indeed has some causal relationship to the course of the illness. This work has been carried on in the United States and in England (Leff et al. 1989). This therapeutic approach has been used with chronic schizophrenia on an outpatient basis (Falloon et al. 1982), with more acutely ill schizophrenia in inpatient settings (Glick et al. 1993), and in brief therapy immediately after hospitalization (Goldstein et al. 1978). We describe the outcome studies for schizophrenia and family interventions in Chapter 24.

Treatment Considerations

In an important follow-up of formerly hospitalized patients with schizophrenia, who had partially recovered—they were asked what had made the difference. They all said, “The key was a relationship with a personal family or friend who believed in them, who talked to them, and who was committed to staying with them.” (Neugenboren 2008).

Modern family interventions have been based partly on the concept of expressed emotion and partly on the increasing evidence that schizophrenia is a disease of the brain. Children with a genetic predisposition to schizophrenia appear to be more sensitive to environmental influences (i.e., parents, peers, poverty) than children who do not have a genetic predisposition (Wahlberg et al. 1997). The shift in caretaking burden to families after the deinstitutionalization movement of the 1950s and 1960s led to the rise in the family advocacy movement. Families demanded services for their family members and themselves that did not blame them for the illness. Because families may perceive the concept of expressed emotion as a form of blaming, an alternative term that appreciates the complexity of this phenomenon is “expressed exasperation.”

Family therapists acknowledged that traditional family therapy techniques were not working and had caused many family members to complain and revolt (i.e., they did not want to be treated by family therapists, preferring biologically oriented professionals).

A ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- A Guide for Using the Text

- Section I: Family Therapy in Context

- Section II: Functional and Dysfunctional Families

- Section III: Family Evaluation

- Section IV: Family Treatment

- Section V: Couples Therapy

- Section VI: Family Treatment When One Member Has a Psychiatric Disorder or Other Special Problem

- Section VII: Results of and Guidelines for Recommending Family Therapy

- Section VIII: Ethical, Professional, and Training Issues

- Index

- EULA