eBook - ePub

Pumps, Channels and Transporters

Methods of Functional Analysis

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pumps, Channels and Transporters

Methods of Functional Analysis

About this book

Describes experimental methods for investigating the function of pumps, channels and transporters

- Covers new emerging analytical methods used to study ion transport membrane proteins such as single-molecule spectroscopy

- Details a wide range of electrophysiological techniques and spectroscopic methods used to analyze the function of ion channels, ion pumps and transporters

- Covers state-of-the art analytical methods to study ion pumps, channels, and transporters, and where analytical chemistry can make further contributions

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pumps, Channels and Transporters by Ronald J. Clarke, Mohammed A. A. Khalid, Ronald J. Clarke,Mohammed A. A. Khalid in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Pharmacology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION

Mohammed A. A. Khalid1 and Ronald J. Clarke2

1Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, University of Taif, Turabah, Saudi Arabia

2School of Chemistry, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

1.1 HISTORY

Modern membrane science can be traced back to 1748 to the work of the French priest and physicist Jean-Antoine (Abbé) Nollet who, in the course of an experiment in which he immersed a pig’s bladder containing alcohol in water, accidentally discovered the phenomenon of osmosis [1], that is, the movement of water across a semipermeable membrane. The term osmosis was, however, first introduced [2] by another French scientist, Henri Dutrochet, in 1827. The movement of water across a membrane in osmosis is a passive diffusion process driven by the difference in chemical potential (or activity) of water on each side of the membrane. The diffusion of water can be through the predominant matrix of which the membrane is composed, that is, lipid in the case of biological membranes, or through proteins incorporated in the membrane, for example, aquaporins. As the title of this book suggests, here we limit ourselves to a discussion of the movement of ions and metabolites through membranes via proteins embedded in them, rather than of transport through the lipid matrix of biological membranes.

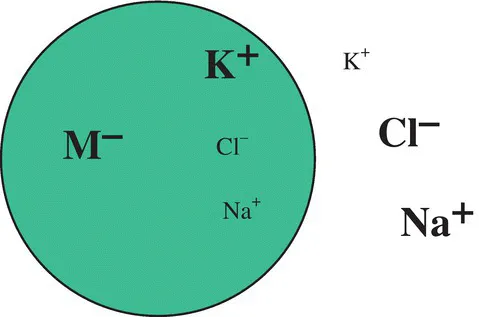

The fact that small ions, in particular Na+, K+, and Cl−, are not evenly distributed across the plasma membrane of cells (see Fig. 1.1) was first recognized by the physiological chemist Carl Schmidt [3] in the early 1850s. Schmidt was investigating the pathology of cholera, which was widespread in his native Russia at the time, and discovered the differences in ion concentrations while comparing the blood from cholera victims and healthy individuals. By the end of the nineteenth century it was clear that these differences in ionic distributions occurred not only in blood, but existed across the plasma membrane of cells from all animal tissues. However, the origin of the concentration differences remained controversial for many years.

Figure 1.1 Ionic distributions across animal cell membranes. M− represents impermeant anions, for example, negatively charged proteins. Typical intracellular (int) and extracellular (ext) concentrations of the small inorganic ions are: [K+]int = 140–155 mM, [K+]ext = 4–5 mM, [Cl−]int = 4 mM, [Cl−]ext = 120 mM, [Na+]int = 12 mM, [Na+]ext = 145–150 mM. (Note: In the special case of red blood cells [Cl−]ext is lower (98–109 mM) due to exchange with HCO3 − across the plasma membrane, which is important for CO2 excretion and the maintenance of blood pH. This exchange is known as the “chloride shift.”) .

Adapted from Ref. 4 with permission from Wiley

In the 1890s at least two scientists, Rudolf Heidenhain [5] (University of Breslau) and Ernest Overton [6] (then at the University of Zürich), both reached the conclusion that the Na+ concentration gradient across the membrane was produced by a pump, situated in the cell membrane, which derived its energy from metabolism. Although we know now that this conclusion is entirely correct, it was apparently too far ahead of its time. In 1902, Overton even correctly proposed [7] that an exchange of Na+ and K+ ions across the cell membrane of muscle—now known to arise from the opening and closing of voltage-sensitive Na+ and K+ channels—was the origin of the change in electrical voltage leading to muscle contraction. This proposal too was not widely accepted at the time or even totally ignored. It took another 50 years before Overton’s hypothesis was rediscovered and finally verified by the work of Hodgkin and Huxley [8], for which they both received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1963. According to Kleinzeller [9], Andrew Huxley once said that, “If people had listened to what Overton had to say about excitability, the work of Alan [Hodgkin] and myself would have been obsolete.”

Unfortunately for Heidenhain and Overton, their work did not conform with the Zeitgeist of the early twentieth century. At the time, much fundamental work on the theory of diffusion was being carried out by high-profile physicists and physical chemists, among them van’t Hoff, Einstein, Planck, and Nernst. Of particular relevance for the distribution of ions across the cell membranes was the work of the Irish physical chemist Frederick Donnan [10] on the effect of nondialyzable salts. Therefore, it was natural that physiologists of the period would try to explain membrane transport in terms of passive diffusion alone, rather than adopt Overton’s and Heidenhain’s controversial hypothesis of ion pumping or active transport.

Donnan [10] suggested that if the cytoplasm of cells contained electrolytically dissociated nondialyzable salts (e.g., protein anions), which it does, small permeable ions would distribute themselves across the membrane so as to maintain electroneutrality in both the cytoplasm and the extracellular medium. Thus, the cytoplasm would naturally tend to attract small cations, whereas the extracellular medium would accumulate anions. Referring back to Figure 1.1, one can see that this idea could explain the distribution of K+ and Cl− ions across the cell membrane. However, the problem is that the so-called Donnan equilibrium doesn’t explain the distribution of Na+ ions. Based on Donnan’s theory, any permeable ion of the same charge should adopt the same distribution across the membrane, but the distributions of Na+ and K+ are in fact the opposite of one another. To find a rational explanation for this inconsistency, many physiologists concluded that, whereas cell membranes were permeable to K+ and Cl− ions, they must be completely impermeable to Na+ ions. The logical consequence of this was that the Na+ concentration gradient should have originated at the first stages of the cell division and persisted throughout each animal’s entire life. This view was an accepted doctrine for the next 30 years following the publication of Donnan’s theory [11].

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, however, evidence was mounting that the idea of an impermeant Na+ ion was untenable. In this period, radioisotopes started to become available for research, which greatly increased the accuracy of ion transport measurements. A further stimulus at the time was the development in the United States of blood banks and techniques for blood transfusion, during which researchers were again investigating the distribution of ions across the red blood cell membranes and the effects of cold storage. Researchers in the United States, in particular at the University of Rochester, Yale University, and the State University of Iowa, were now the major players in the field, among them Fenn, Heppel, Steinbach, Peters, Danowski, Harris, and Dean. Details of the experimental evidence that led to the universal discarding of the notion of an impermeant Na+ ion and the reemergence of the hypothesis of an active Na+ pump located in the cell membrane of both excitable and nonexcitable cells are described elsewhere [4, 12, 13]. Here it suffices to say that by the middle of the twentieth century th...

Table of contents

- COVER

- TITLE PAGE

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- PREFACE

- LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

- 1 INTRODUCTION

- 2 STUDY OF ION PUMP ACTIVITY USING BLACK LIPID MEMBRANES

- 3 ANALYZING ION PERMEATION IN CHANNELS AND PUMPS USING PATCH-CLAMP RECORDING

- 4 PROBING CONFORMATIONAL TRANSITIONS OF MEMBRANE PROTEINS WITH VOLTAGE CLAMP FLUOROMETRY (VCF)

- 5 PATCH CLAMP ANALYSIS OF TRANSPORTERS VIA PRE-STEADY-STATE KINETIC METHODS

- 6 RECORDING OF PUMP AND TRANSPORTER ACTIVITY USING SOLID-SUPPORTED MEMBRANES (SSM-BASED ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY)

- 7 STOPPED-FLOW FLUORIMETRY USING VOLTAGE-SENSITIVE FLUORESCENT MEMBRANE PROBES

- 8 NUCLEAR MAGNETIC RESONANCE SPECTROSCOPY

- 9 TIME-RESOLVED AND SURFACE-ENHANCED INFRARED SPECTROSCOPY

- 10 ANALYSIS OF MEMBRANE-PROTEIN COMPLEXES BY SINGLE-MOLECULE METHODS

- 11 PROBING CHANNEL, PUMP, AND TRANSPORTER FUNCTION USING SINGLE-MOLECULE FLUORESCENCE

- 12 ELECTRON PARAMAGNETIC RESONANCE: SITE-DIRECTED SPIN LABELING

- 13 RADIOACTIVITY-BASED ANALYSIS OF ION TRANSPORT

- 14 CATION UPTAKE STUDIES WITH ATOMIC ABSORPTION SPECTROPHOTOMETRY (AAS)

- 15 LONG TIMESCALE MOLECULAR SIMULATIONS FOR UNDERSTANDING ION CHANNEL FUNCTION

- INDEX

- CHEMICAL ANALYSIS

- END USER LICENSE AGREEMENT