- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Ecosystem Dynamics focuses on long-term terrestrial ecosystems and their changing relationships with human societies. The unique aspect of this text is the long-time scale under consideration as data and insights from the last 10,000 years are used to place present-day ecosystem status into a temporal perspective and to test models that generate forecasts of future conditions. Descriptions and assessments of some of the current modelling tools that are used, along with their uncertainties and assumptions, are an important feature of this book. An overarching theme explores the dynamic interactions between human societies and ecosystem functioning and services.

This book is authoritative but accessible and provides a useful background for all students, practitioners, and researchers interested in the subject.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ecosystem Dynamics by Richard H. W. Bradshaw,Martin T. Sykes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecosystems & Habitats. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Where Are We and How Did We Arrive Here?

‘I could calculate your chance of survival, but you won't like it.’The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams, 1979

1.1 Why this book?

In January 2013 the Australian Bureau of Meteorology had to increase the temperature range of its standard weather forecasting chart by 4 °C to a maximum of 54 °C, adding deep purple and pink to its colour palette. The new colours were put into immediate action as old temperature records toppled in the latest heatwave, following what the government's Climate Commission called an ‘angry summer’. This is just one symptom of change that will influence global ecosystems, and it is important for all whose livelihoods and food are linked to the land to know what these impacts will be. Providing projections of the impacts is a challenge that we can meet either by studying records of past warmer periods or by using models to forecast the future. These two approaches are linked, as forecasting models have to build on knowledge and experience from the past. This link between models and data is one of the motivations and central themes of our book.

This book is about the long-term dynamics of the terrestrial ecosystems of the Earth. These ecosystems only cover 29% of the surface of the planet, but that is where we live, produce much of our food and gather most of our raw materials. The oceans and freshwaters of the world are also of vital importance for civilisations past and present, but in this book we concentrate on the dry land systems. We need to understand the changes taking place around us in order to be able to manage and exploit ecosystems in appropriate ways in the future. To do this we must have adequate descriptions, both of the system dynamics and of the forces that cause or shape these dynamics. The current state of many ecosystems is a consequence of dynamics, forces and events that have operated over very long periods; the timespan we cover stretches back over 20 000 years, to the coldest part of the last ice age, and reaches forward 100 years into the future. There are several factors that influence ecosystem dynamics but the most important are climate change, human impact and the physiological constraints of individual species. Specialised geological techniques are needed to explore the past, and modelling carries our analyses into the future. Our combination of data and modelling helps us understand how we arrived at the present state of the world and where we might be headed.

We two authors have expertise in long-term ecosystem dynamics that result in population and range changes of individual species. We both have a botanical background, so we use more plant than animal examples, although humans are the species most often mentioned. For long-lived trees, we examine both rapid events like forest fires and slow events like the range changes that occurred as Europe became revegetated after the last ice age. The ecosystem concept comprises species interactions with soils, water and the atmosphere, but inevitably our treatment reflects our own interests and experience and may be uneven. As biologists we are more conversant with the biotic components and processes than the abiotic, and there is more coverage of large plants and animals than of microorganisms. Humans are at the centre of this book. We analyse the development through time of the way people interact with the ecosystems that they have come to dominate. We write little about the present day as that is well covered in numerous other sources.

Models are another central topic in the book. They are sophisticated tools for integrating our knowledge of the Earth system and exploring the future. Models have a symbiotic relationship with data, which we examine in this book. Models draw on data during their construction and must be tested against yet more data. Models are not real life but can be used as experimental tools to explore the nature and relationships of the systems under study to generate future scenarios and even forecasts. They give outputs that may or may not be correct but can be assessed for validity against available data, for example through hindcasting: the comparison of known past events with model output. Hindcasting can increase understanding of past ecosystems and boost confidence in the explanatory power of models, and it is one important focus of this book. The overall aim of ecosystem modelling is to improve insight into and understanding of the complex interactions within an ecosystem, such as the responses to past or future variations in climate. Models can generate insight but do not necessarily provide definite answers, because they are, after all, only models. Once the model output has been validated against data, the model becomes a more effective and convincing tool with which to explore possible futures.

1.2 Ecosystems in crisis

The human race has now moved into the driving seat of all terrestrial ecosystems and the control panel is complex. There is no owner's manual and several systems are already careering out of control. There is an urgent need to understand these controls and to use our power wisely. This book provides the background information needed to ensure a long, sustainable relationship between planet Earth and its new managers and prepares the ground for writing that owner's manual. The control panel has warning lights and touch controls that alter land cover, emission of gases, hydrology, soil properties, genetic diversity and several other factors. Guidelines are needed for the appropriate settings and there is some urgency as several warning lights are flashing, including those labelled ‘greenhouse gas emissions’, ‘rapid climate change’, ‘biodiversity loss’, ‘food security’ and ‘water supply’. These warning lights show that the resilience of several ecosystems is being put to the test.

There are enormous issues at stake, including the future of ecosystem goods and services such as agriculture and silviculture, water and soil resources and the carbon and nitrogen cycles. There is active debate about how many people can survive on the planet in the longer term. Can the Earth support 12 000 000 000 people or are we threatened by severe and painful population reductions, such as occurred in the distant past? What are the prospects for the long-term survival of the human race? The term Anthropocene has been introduced to describe the last 200 years, in which ‘our societies have become a global geophysical force’, a process that has accelerated during the last 35 years (Steffen et al., 2007). It is not easy to put a precise date on when humans took over control of the planet from natural forces such as competition between species, natural selection, fire, weathering of rock and hydrological cycles, but the 200 years of the Anthropocene is one convenient estimate as good data exist from that period, although others have argued for the first millennium AD. Humans today move an order of magnitude more rock, soil and sediment during construction and agriculture than the sum of all other natural processes that operate on the surface of the planet put together. If the erosion of rock and soil caused by construction and agriculture were evenly distributed over ice-free continental surfaces, these human activities would now lower land surface by a few hundred metres per million years, as compared with an earlier estimated natural rate of a few tens of metres per million years (Wilkinson, 2005). We are also exploiting many of the same ecosystem processes that were operating in the past, but our exploitation is now so intensive that we have considerably amplified or modified their rates, properties and effects. Fire is one ecosystem process that has become totally altered through its deliberate use in agriculture and its suppression to protect forest resources, as well as the manipulation of fuels. The management of grazing animals and the selection of genotypes of plants and animals that are favourable for us are further examples of the ways in which we have modified ecosystem processes and properties. Our owner's manual draws on past experience to propose appropriate uses of the ecosystem controls.

Human society faces several developing crises in ecosystem services that are making warning lights flash on our control panel. The global economy is almost five times the size it was half a century ago and such a rapid increase has no historical precedent (Jackson, 2009). The associated increase in use of finite natural resources and management of increased land areas has led to rapid conversion of terrestrial biomes into agricultural land, plantations, wasteland and cities, with consequent loss of species and modification of ecosystem services. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) has identified those services that are rapidly degrading, which include freshwater, wild foods, wood fuel, soil volume and quality, genetic resources and natural hazard regulation by wetlands and mangroves (www.maweb.org). Terrestrial ecosystems provide key components of the natural capital and services that fuel much current economic growth. They probably always fulfilled this function for hunter-gatherer societies and subsequent civilisations, but never on the scale posed by current demands. Agriculture lies behind much ecosystem transformation and is a contributory factor to major environmental concerns, including loss of biodiversity, overexploitation of freshwater, soil degradation and even climate change. Yet about one in seven people are chronically malnourished (Foley et al., 2011). The amount of land dedicated to cereal production per person has been reduced from 0.23 ha in 1950 to 0.1 ha in 2007, increasing the challenge involved in feeding the growing global population. There is also growing competition between individual services as terrestrial ecosystems become more heavily exploited. Most of the Earth's surface that is suitable for arable agriculture is now utilised, and maize, rice and wheat provide over 30% of their essential daily food to more than 4.5 billion people (Shiferaw et al., 2011). However, competing demands for the use of maize, both as animal feed and for its conversion into bioethanol for fuel, have driven up prices in an alarming manner, with significant social consequences.

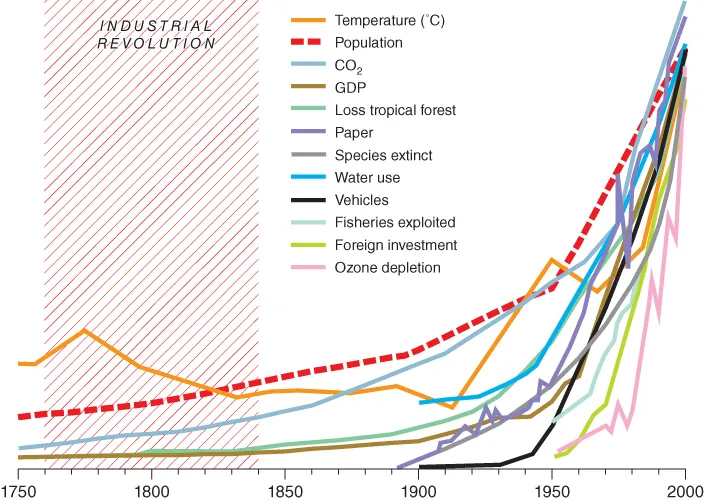

It is sobering to consider the global development of population size since AD 1750 and its consequences , which include demands on some major ecosystem services such as water use and fisheries (Figure 1.1; Steffen et al., 2004, cited in Dearing et al., 2010). No complex analysis is needed to understand that as the population curve climbs, reduction of tropical forest area, number of species extinctions and loss of sustainable fish stocks are likely to follow, along with global gross domestic product (GDP) and other economic indicators, such as the number of vehicles on the road (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Changes in global states and processes since AD 1750—including ecosystem services, climate variables and economic data—all show acceleration in rates from the mid-twentieth century (after Steffen et al., 2004, Dearing et al., 2010 and Ehrlich et al., 2012)

All around us we can see the ecosystem consequences of the rapidly increasing human population, which is coupled to the demands we make on our environment and fuelled by technologies and energy sources developed during the industrial revolution. Recent and forecasted future global population dynamics are the herd of elephants in the room that underlie all that is written about current and future global change. While it is proving possible in several regions of the world to influence family size, which is usually closely linked to social equality and levels of education, the associated increasing consumption of natural resources is proving to be far harder to control (Ehrlich et al., 2012). The inexorable spread of consumer culture from developed to developing economies is driven by too powerful forces to be managed by normal governmental regulatory tools. The usually cautious United Nations Secretary-General has called for revolutionary action in the developed world to replace the prevailing model of economic growth, which is driven by extravagant use of natural resources. He has described this model as ‘a global suicide pact’.

Every previous period of human society has had its concerns, worries and prophets of doom. Here we are with more people than ever before, who are living longer and have access to resources and knowledge on an entirely different scale from previous generations, yet many researchers share the foreboding of the Secretary-General and feel that the increasing pressure on global ecosystems is precipitating a crisis that will be impossible to resolve by technological means alone and will result in social dislocation and suffering. This book provides a background to the consequences for terrestrial ecosystems of the current state of affairs and reviews the tools that can help explore possible future scenarios.

Rockström et al. (2009) introduced the concept of a safe operating space for the Earth, in which they feel their way towards the planetary boundaries of the Earth system (Figure 1.2). They identify nine critical processes for which thresholds of control variables such as atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration should be defined—although this is easier said than done. If these notional thresholds are crossed, the consequence could be ‘unacceptable environmental change’. They suggest that three processes have already exceeded these safe operating limits, namely climate change, the rate of biodiversity loss and interference with the global nitrogen cycle. A particular concern they raise relates to ‘tipping points’, which describe the tendency of complex Earth systems not to respond smoothly to changing pressures but rather ‘to shift into a new state, often with deleterious or potentially even disastrous consequences for humans’ (Rockström et al., 2009). There is an urgent need to identify potential thresholds within Earth systems, which once crossed will alter their states in ways that could have alarming consequences for civilisation. Our agriculture is highly dependent on the regularity of monsoon systems and the timing of spring, for example, so we need to understand any nonlinear responses of these climatic features to global warming. Could a reduction in the cover of arctic sea ice elicit a nonlinear response in the northern hemisphere growing season? This feels like an immediate concern as farmers bemoan one problem after another and survey the poor condition of their winter cereals during late, cold springs. Many of the Earth's subsystems do appear to react in a nonlinear, often abrupt, way and are particularly sensitive around threshold levels of certain key variables. If these thresholds are crossed then important subsystems, such as a monsoon system, could shift into a new state, posing problems for sustained agricultural production. The concepts of critical tipping points and nonlinear responses to press...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Acknowledgements

- About the companion website

- Chapter 1: Where Are We and How Did We Arrive Here?

- Chapter 2: Modelling

- Chapter 3: Data

- Chapter 4: Climate Change and Millennial Ecosystem Dynamics: A Complex Relationship

- Chapter 5: The Role of Episodic Events in Millennial Ecosystem Dynamics: Where the Wild Strawberries Grow

- Chapter 6: The Impact of Past and Future Human Exploitation on Terrestrial Ecosystem Dynamics

- Chapter 7: Millennial Ecosystem Dynamics and Their Relationship to Ecosystem Services: Past and Future

- Chapter 8: Cultural Ecosystem Services

- Chapter 9: Conservation

- Chapter 10: Where Are We Headed?

- References

- Glossary

- Index

- End User License Agreement