![]()

PART 1

Design of Human–Machine Systems

![]()

1

Human-centered Design

Patrick Millot

1.1. Introduction

The theme covered in this chapter is the design of dynamic systems, of production, transport or services, that integrate both human operators and decision or command algorithms. The main question during the designing of a human–machine system concerns the ways of integrating human operators into the system.

As mentioned in the Introduction, human-centered design of human–machine systems must take into account five dimensions and the relations between them: not only the operator, the system and the tasks to be carried out, but also the organization and the situation of the work. These five dimensions are tightly linked; the tasks are different depending on the type of system, particularly its level of automation, but also depending on the potential situation and the expected safety level, the organization of the agents in charge of operating it (operators and/or automatic operating systems). The manner in which the tasks are carried out depends on the human operators themselves, who have different profiles depending on their training, aptitudes, etc.

In section 1.2, we cover the diversity of the tasks human operators are faced with, and the difficulties that they encounter in various situations. The models that explain the mechanisms of reasoning, error management and maintaining situation awareness (SA) are then explored. The creation of tools to support either action or decision in difficult situations leads to a modification of the level of automation, and as a result the global organization and the task or the functions sharing between humans or between humans and machines. The concepts of authority and of responsibility are then introduced. All of these points are the topics of section 1.3. Section 1.4 draws these different concepts together into a method of design-evaluation of the human–machine systems.

1.2. The task–system–operator triangle

1.2.1. Controlling the diversity of the tasks depending on the situation

First of all, we must make the distinction between the task, which corresponds to the work that is “to be done”, and the activity, which corresponds to the work carried out by a given operator, who has his own aptitudes and resources. Thus, to carry out the same task, the activity of operator 1 can be different from the activity of operator 2.

The tasks themselves depend on the system and the situation, as the latter can be either normal or abnormal, or even dangerous. The level of automation determines the level of human involvement in the interaction with the system: often in highly automated systems, humans rarely intervene during normal operation. However, they are often called upon during abnormal situations and for difficult tasks. The example of the supervision of nuclear power plants is given hereafter.

In systems with low levels of automation, such as the automobile, the operators are involved both in normal situations (driving on clear roads in normal weather) and in difficult situations such as during the sudden appearance of an object at night in snowy weather. The involvement of the driver is then different.

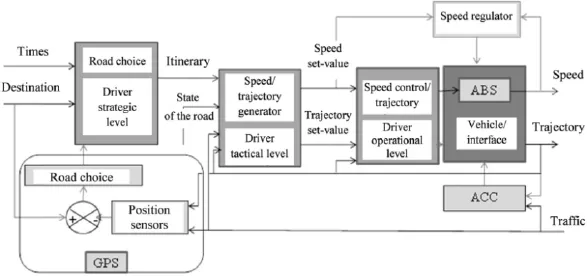

To be able to deal with the difficulty of a task, we can attempt to decompose it. For example, the task of driving an automobile can be functionally decomposed into three sub-tasks according to three objectives (see Figure 1.1):

– strategic, to determine the directions between the start point and the destination;

– tactical, to define the trajectory and the speed on the chosen road; and

– operational, to control the speed and the trajectory of the vehicle on the road.

Functionally, this can be decomposed in a hierarchic manner, the three subtasks performed by the driver having different having different temporal horizons, and the functions and the resources necessary to execute each of these also being different. Assistance tools are also added which can be applied to specific sub-tasks: the speed regulator, ABS brakes (the wheel anti-blocking system) and automated cruise control (ACC) are applied to the operational sub-task, and GPS to the strategic sub-task. These additions are only assistance tools, i.e. they do not increase the level of automation since the human operator remains the sole actor.

Figure 1.1. Diagram of the task of automobile driving according to three objectives

An increase in the level of automation could, however, be applied to one of the sub-tasks, for example the ABV project (Automatisation à Basse Vitesse, or low speed automation), which aims to make driving in peri-urban areas completely autonomous through automation, for speeds that are below 50 km/h [SEN 10], or the “Horse Mode project”, which is inspired from the horse metaphor, in which the horse can guide itself autonomously along a road, and the horse rider deals with the tactical and strategic tasks. A corollary project is looking into sharing the tasks between the human pilot and the autopilot [FLE 12], and we will look into it further later on.

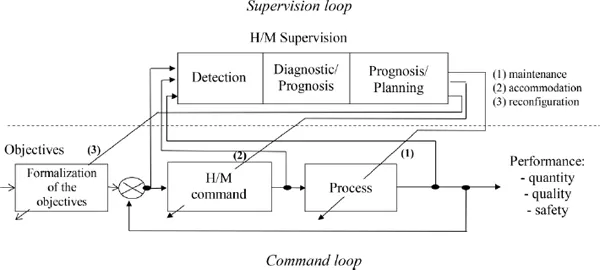

At the other end of the spectrum, a nuclear power plant is a highly automated system that is very big (around 5,000 instrumented variables), complex (lots of interconnection between the variables) and potentially very risky. The tasks of the operators in the control room have shifted from the direct command level to the supervision level (see Figure 1.2). These are therefore decision tasks for monitoring, i.e. fault detection diagnosis to determine the causes and the faulty elements involved and decision-making to define the solutions. These can be part of three types: a maintenance operation to replace or repair the faulty element; accommodation (adaptations) of the parameters to change the operation point; or, finally, reconfiguration of the objectives, for example, to favor fallback objectives when the mission is abandoned or shortened. Planning consists, for example, of decomposing the solutions by giving them hierarchy according to the strategic, tactical or operational objectives like the ones shown above1.

Figure 1.2. Principles of supervision

The highly automated systems are also characterized by differences in the difficulty of the tasks, i.e. the difficulty of the problems to be solved during supervision, depending on whether the situation is normal or abnormal, for example during the supervision of critical systems where time-related pressure further increases stress: nuclear industry, civil aviation, automatic metro/underground systems. To deal with these difficulties, the operators require resources, which, in these cases, is the knowledge required to be able to analyze and deal with the operation of the system, with the goal of coming up with a diagnosis. This knowledge can then be used to write up procedure guides or diagnostic support systems. A distinction can be made between the following:

– knowledge available to the designers: on the one hand, about the function of the components, and on the other hand, topological, i.e. related to the positioning and the interconnections between the components [CHI 93]; and

– knowledge acquired during usage by the supervision and/or maintenance teams during the resolution of the successive problems. These can be functional, i.e. related to the modes of functioning or of malfunctioning of these components, and behavioral or specific to a particular situation or context [JOU 01].

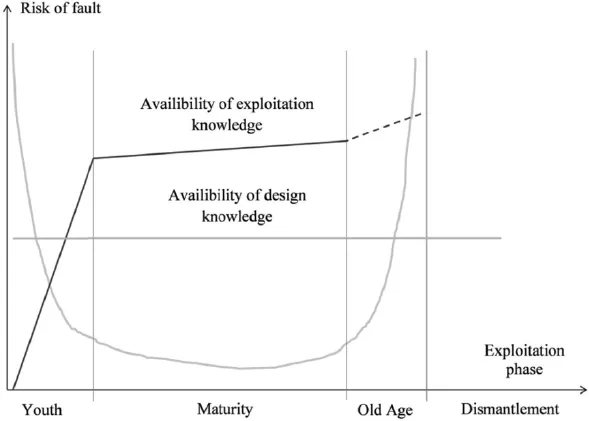

Figure 1.3. Knowledge requirements throughout the life cycle of a system

The difficulties of the tasks in the different situations of operation are modulated by the degree of maturity of the system (see Figure 1.3), which has an influence on the availability of this knowledge:

– The early period of youth is the one which requires the most adjustments and updates and where the system is the most vulnerable to faults: the problem being that the operators have not yet accumulated enough experience to control and manage the system at this stage (REX “retour d’expérience”: feedback experience) to effectively deal with system malfunctions. However, knowledge of the process design is available, but not always very clear or well modeled, describing the structure and the topology of the system, i.e. its components, their operation modes and the relations between them. This knowledge can make up a strong basis to help during the process exploitation phases. In Chapter 6, Jacky Montmain describes a method of modeling that is based on the relations of causality between the variables. This is important for the composition of the diagnostic support systems which are based on a model of normal operation of the process when expert knowledge of possible malfunction is not yet available [MAR 86].

– In the period of maturity, both exploitation knowledge and knowledge of design are available; often they are transcribed in the form of exploitation and/or maintenance procedures. Moreover, the risks of fault due to youth imperfections are reduced, both for the system and the operators.

– Finally, during the period of old age, the process presents an increasing number of faults due to wearing of the components, but the operators have all the necessary knowledge to deal with this, or to apply a better maintenance policy.

Air traffic control is another example of a risky system with a low level of automation and a high number of variables, namely the airplanes and their flight information. Problems, called aerial conflicts, take place when two or more planes head toward each other and risk a collision. It is then up to air traffic controllers to preventatively detect these conflicts and to resolve them before they take place, by ordering the pilot(s) to change their trajectory. Considering the expertise of the controllers, the difficulty does not lie so much in the complexity of the problems to be solved, but rather in their sheer number, especially during periods of heavy traffic2. Thus, tens of minutes can pass between the moment of detection of a conflict by a controller and the adequate moment when the resolving order is transmitted to the relevant pilot(s). In this way, the controller risks forgetting the conflict and sending the order too late. Several practical cases in this book involve air traffic control.

After this overview of the diversity of the tasks, depending on the types of systems and the situations, we now move on to look at the approaches to modeling the system itself, and the methods to be developed so as to attempt to make their understanding easier.

1.2.2. Managing the complexity of the system

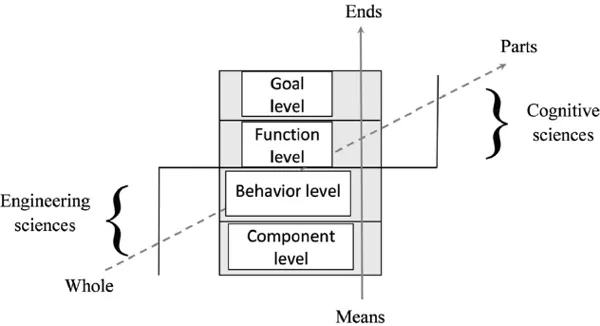

The large dimension of the technical system makes classical modeling and identification techniques extremely time consuming and leads to models that are not suited to real-time simulations. This has been the basis for work on hierarchical modeling in the systems trend led by Lemoigne [LEM 94], producing several methods of analysis and of modeling, such as SAGACE [PEN 94]. SADT follows the same idea, which relies on a decomposition of the global system. More recently, the multilevel flow modeling (MFM) method by Lind decomposes the system according to two axes: the means/ends axis and the all/part axis (see Figure 1.4) [LIN 10, LIN 11a, LIN 11b, LIN 11c].

Figure 1.4. MFM multilevel decomposition of a large system according to Lind

According to the means/ends axis, there are four levels of model, from the most global (and least detailed) to the grainiest: the goals, the functions, the behaviors and the components. The models of one level are thus the goals of the models of the lower level and the means of the higher level. Let us note that the models of control theory are found at the level of behavior and very technical models, for example electronic and mechanical models found at the level of components. These two levels are part of engineering sciences. The two higher levels are themselves part of the cognitive sciences and concern the nature and the realization of the more global functions (and their sequencing), ensured by the behaviors of the physical level. Among the possible methods of modeling, we can cite the qualitative models [GEN 04], Petri networks, etc. The making of decisions related to the putting in place of the functions is often the result of optimization algorithms, or even human expertise, which is therefore symbolic, and which can be put into place through certain rules. This starts to be part of the domain of artificial intelligence (AI).

Decomposition according to the whole/part axis is the corollary of the decomposition imposed by the means/ends axis: the closer we are to the ends or goals, the more the entirety of the system is taken into account, the closer we are to the means, the more the model involves the different parts. This method of modeling puts new light on the subjects concerned and shows their complementarity. It most importantly shows that disciplines other than the physical sciences are involved in this vast issue. The method of modeling of the human operator has also followed a similar evolution.

1.2.3. Managing human complexity

A lot of multi-disciplinary research has been conducted on human factors since World War II, and a significant amount of methodological know-how has resulted. The goal here is not to produce a comprehensive review of this, but to introduce the designer with well-established and understandable models that help bring constructive and accurate results, even if, in the eyes of the most meticulous specialist, they may appear incomplete or simplified. Three points appear to be most important, knowing that in reality human behavior is a lot more complex; we will discuss other sociological aspects later in the chapter:

– the operator’s adaptive behavior to regulate his workload during the execution of a task;

– reasoning mechanisms and decision-making mechanisms that the operator uses during complex decision tasks, such as in the supervision of the large, risky automated systems (nuclear power plants, chemical plants, etc.), but also during reactive tasks (which a short-response time) such as piloting an airplane or during the driving of an automobile; and

– mechanisms of errors and suggestions of solutions to deal with them.

1.2.3.1. The regulation of human activity

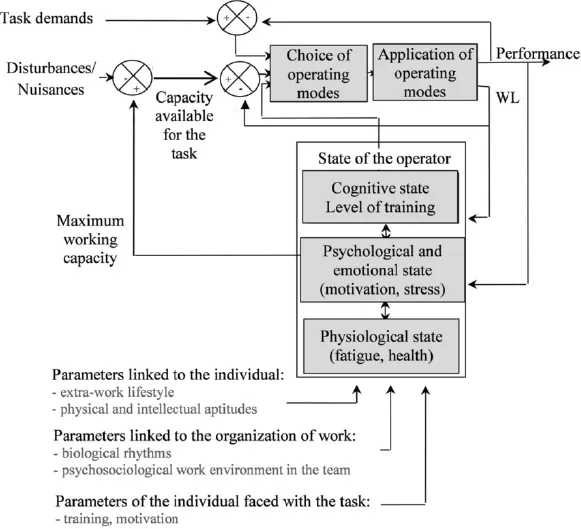

The system of the “human operator carrying out a task” can be considered to be a complex, adaptive system, made up of interconnected sub-systems, partially observable and partially commandable. A summary produced by Millot [MIL 88a] is presented in Figure 1.5. It brings together the inputs of the system, disturbances and the internal state parameters affecting the outputs of the system. Human functioning is modeled by three regulation loops with three objectives: in the short term, the regulation of performance; in the medium term, the regulation of the workload caused by the task; and in the long term, regulation of the global load, due to the global environment but also to the internal state of the operator.

Figure 1.5. Model of the regulation of human activity (from a detailed summary in [MIL 88])

1.2.3.1.1. Inputs and outputs of the “human operator carrying out a task” system

The inputs are the demands of the task, i.e. the characteristics of the work to be accomplished, gathering the objectives to be reached. These are translated as timeframes to be respected and specific difficulties due to the task and/or the interface.

Nuisances that are not linked to the task can disturb the system. They are induced by the physical environment, and come in the form of vibrations, sound, light, heat, etc. Some of these disturbances increase the difficulties of the task, for example the reflection of lights on a screen, or vibrations of the work surface during manual control. One of the objectives of ergonomics is first to arrange the environment of workstations to reduce or even eliminate these nuisances.

The output is the performance obtained during the execution of the task. Observation of the performance is one of the methods possible to evaluate the ergonomic characteristics of a human–machine system. It is obvious that one of the big methodological difficulties relates to the choice of performance evaluation criteria. Generally, it is defined in terms of production indices, whether quantitative or qualitative, that are directly relative either to the procedures applied by the operator (response time, error rate, strategies, etc.) or to the output of the human–machine system, for example a product in the case of a production system. It also integrates criteria linked to safety and to security, particularly for critical systems [MIL 88]. Ten years later, ergonomists have joined this idea by underlining the necessity to take into account the performance of the human–machine system as an evaluation criterion during conception (see Chapter 2 by C. Chauvin and J.-M Hoc).

1.2.3.1.2. Workload

To carry out the task, the operator chooses the operating modes, which, once applied, produce a certain performance. If the operator has some knowledge of his performance, he can refine it by modifying his operating modes. But the performance alone is not enough to characterize the state of mobilization of the operator induced by the task and thus to evaluate the difficulties really encountered during its execution. For this, ergonomists use a state variable, called workload, which corresponds to the fraction of work capacity that the operator invests in the task. Sperandio defines this as the “level of mental, sensorimotor and physiological activity required to carry out the task” [SPE 72].

The operator carrying out the task has a certain amount of work c...