![]()

Part I

Introduction and Basics of Advanced Drug Delivery

![]()

1

Physiological Barriers in Advanced Drug Delivery: Gastrointestinal Barrier

D. Alexander Oh and Chi H. Lee

1.1 Chapter objectives

1.2 Introduction

1.3 Physiological factors influencing drug absorption

1.4 Physicochemical factors influencing drug absorption

1.5 Strategies to overcome gastrointestinal barriers in drug delivery

1.6 Summary

Assessment questions

References

1.1 Chapter Objectives

- To outline gastrointestinal anatomy and physiology impacting advanced oral drug delivery systems.

- To review key physiological and physicochemical factors influencing drug absorption.

- To illustrate efficient strategies for overcoming gastrointestinal barriers in drug delivery.

1.2 Introduction

Drug delivery through oral administration is a complicated process: A drug must withstand the digestive processes and penetrate through the gastrointestinal (GI) barrier into the bloodstream. Drugs absorbed from the GI tract travel through portal veins to the liver, and then they are subjected to first-pass metabolism by the hepatic enzymes before entering the systemic circulation [1]. The oral route of drug administration is traditionally known as the most preferred route for systemic drug delivery, even though there are disadvantages, such as unpredictable and erratic absorption, gastrointestinal intolerance, incomplete absorption, degradation of drug in GI contents, and presystemic metabolism, mostly resulting in reduced bioavailability.

The primary functions of the GI tract are absorption and digestion of food, as well as secretion of various enzymes or fluids [2]. The gastrointestinal mucosa forms a barrier between the body and a luminal environment that contains not only nutrients but also potentially hostile microorganisms and toxins. The normal function of the GI barrier, which is referred to the properties of the gastric and intestinal mucosa, is essential for disease prevention and overall maintenance of health. The major challenge in drug delivery through the GI tract is to achieve efficient transport of nutrients and drugs across the epithelium while rigorously excluding passage of harmful molecules and organisms into the body.

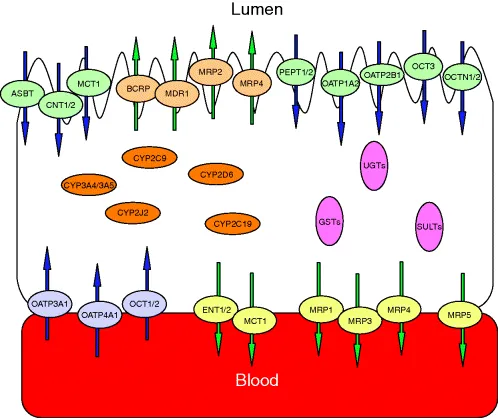

The performance of GI barriers to drug transport may largely depend on the physicochemical characteristics of drugs. Water-soluble small molecules may not be easily absorbed unless a specific transporter to those molecules is present, while lipophilic drugs can be relatively well absorbed through GI barriers. Mucosal transporters include PEPT, OATP, OCT, MCT, ASBT, MDR1, MRP, and BCRP among others [3] as shown in Figure 1.1. Large-molecule drugs, such as antibodies and proteins, may suffer extensive enzymatic degradation in the GI tract [4].

In this chapter, gastrointestinal mucous membranes and gut physiology will be intensively covered from the perspective of physiological barriers, which will lead to thorough understanding of key obstacles to advanced oral drug delivery.

1.2.1 Anatomy of Gastrointestinal Tract

1.2.1.1 Gastrointestinal Anatomy

The major components of the gastrointestinal tract are the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. The small intestine with a length of about 6 m includes the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum [5]. The stomach is a pouch-like structure lined with a relatively smooth epithelial surface. Extensive absorption of numerous weakly acidic or nonionized drugs and certain weakly basic drugs were demonstrated in the stomach under varying experimental conditions [2,6,7].

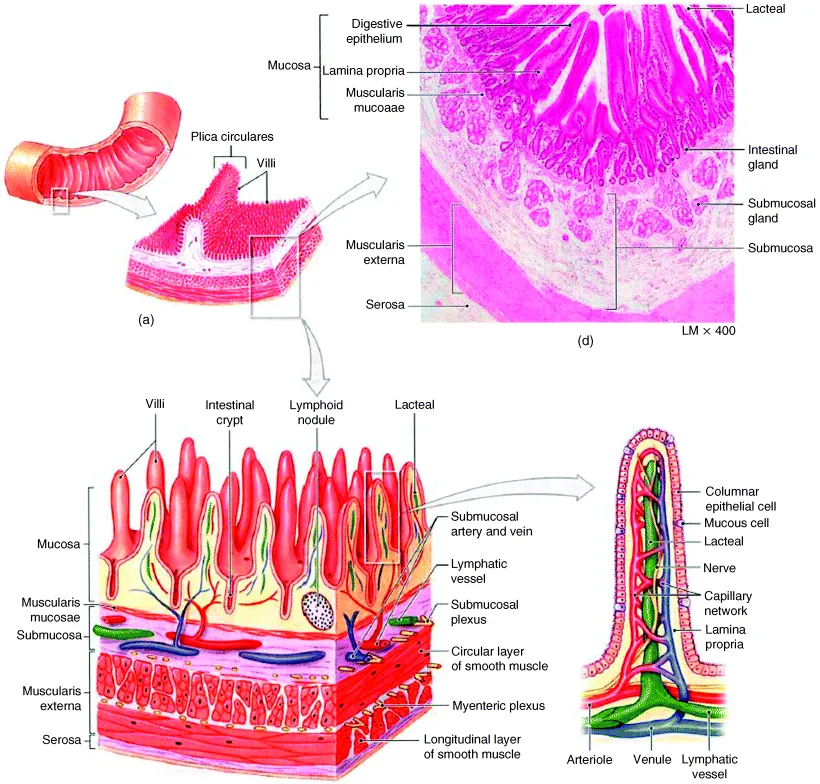

The small intestine is the most important site for drug absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. The epithelial surface area through which absorption of drug takes place in the small intestine is enormously large because of the presence of villi and microvilli, finger-like projections arising from and forming folds in the intestinal mucosa as shown in Figure 1.2 [8]. The surface area decreases sharply from proximal to distal small intestine and was estimated to range from 80-cm2/cm serosal length just beyond the duodeno-jejunal flexure to about 20-cm2/cm serosal length just before the ileo-cecal valve in humans [9]. The total surface area of the human small intestine is about 200 to 500 m2 [6,7]. The small intestine is made up of various types of epithelial cells, i.e., absorptive cells (enterocytes), undifferentiated crypt cells, goblet cells, endocrine cells, paneth cells, and M cells. There is also a progressive decrease in the average size of aqueous pores from proximal to distal small intestine and colon [10,11].

The small intestine is the most involved region for carrier-mediated transport of endogenous and exogenous compounds. The proximal small intestine is the major area for absorption of dietary constituents including monosaccharides, amino acids, vitamins, and minerals. Both vitamin B12 and bile salts appear to have specific absorption sites in the ileum [2]. The large intestine has a considerably less irregular mucosa than the small intestine.

1.2.1.2 Pores

The aqueous pores render the epithelial membranes freely permeable to water, monovalant ions and hydrophilic solutes with a smaller molecular size [2,6,7]. It was estimated that the hypothetical pores in the proximal intestine have an average radius of 7.5 Å, and those in distal intestine (ileum) have that of about 3.5 Å [10]. The pore sizes of the aqueous pathway for buccal and sublingual mucosa in pigs were estimated as 18–22 and 30–53 Å, respectively [12]. Since the molecular size of most drug molecules are larger than a pore size in the membrane, drug transport through pores seems to be of minor importance in drug absorption. However, some larger polar compounds with molecular weights up to several hundreds are still absorbed through active participation of the membrane components.

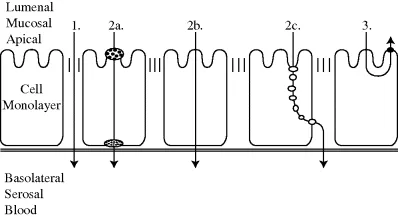

1.2.1.3 Tight Junctions

Tight junctions are closely associated areas of two cells whose membranes join together, forming a virtually impermeable barrier to fluid. Tight junctions are composed of the structural proteins (occludin and claudins), the scaffold proteins (ZO-1, ZO-2, fodrin, cingulin, symplekin, 7H6, and p130), and the actin cytoskeleton [13]. Paracellular transport of drugs mostly occurs via tight junctions (Figure 1.3). The permeability of intestinal epithelium to large molecules or ionized drugs depends on the combination of transcellular transport via adsorptive endocytosis and paracellular transport through tight junctions.

Tight junctions were conceptualized a century ago as secreted extracellular cement, forming an absolute and unregulated barrier within the paracellular space [2,6,7]. The contribution of the paracellular pathway of the gastrointestinal tract to the general correlation between environment and host molecular interaction was considered to be negligible. It is apparent that tight junctions have extremely dynamic structures engaged with developmental, physiological, and pathological situations.

To date, particular attention has been placed on the role of tight junction dysfunction in the pathogenesis of several diseases, particularly autoimmune diseases with viral etiology [2,6,7]. Pathophysiological regulation of tight junctions is influenced by various factors including secretory IgA, enzymes, neuropeptides, neurotransmitters, dietary peptides and lectins, yeast, aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, parasites, proinflammatory cytokines, free radicals, and regulatory T-cell dysfunction [2].

1.2.2 Gastrointestinal Physiology

A comprehensive review of the physiological parameters that affect oral absorption in the context of formulation performance and drug dissolution was recently published [14]. This physiologically relevant information to oral human drug delivery could serve as a basis for the design of advanced drug delivery systems.

1.2.2.1 Gastrointestinal Components

i. Bile Salts. Bile salts are known to enhance the absorption of hydrophobic drugs by enhancing their wettability. The absorption rates of such drugs as griseofulvin can be facilitated when they are taken after meals as a result of the increase of bile salts excretion that promotes their dissolution rates [2]. On the contrary, bile salts reduced the absorption of certain drugs, such as aminoglycosides, neomycin, and nystatin, through the formation of nonabsorbable complexes with bile salts [15].

ii. Mucin. Mucin is a viscous muco-polysaccharaide (glycoprotein) that lines the gastrointestinal mucosa for protection and lubrication purposes [16]. Mucin has a negative anionic charge, so it may form a nonabsorbable complex with some drugs, such as aminoglycosides and quaternary ammonium compounds, subsequently affecting their absorption.

iii. Enzymes. Since GIT fluid contains high concentrations of enzymes needed for food digestion, some enzymes may act on drugs. For example, esterases secreted by pancreas affect the metabolic process of ester derivative drugs including aspirin and propoxyphene through the hydrolysis process in the intestine [17]. In epithelial cells, ...