![]()

Chapter 1

Hydraulic Fracturing Overview

1.1 Technology Overview

Oil and gas are naturally occurring hydrocarbons sought after by all of mankind because of their energy value and ability to manufacture an almost infinite number of chemically derived products. Two elements, hydrogen and carbon, make up a hydrocarbon. Because hydrogen and carbon have a strong attraction for each other, they form many compounds. The oil industry processes and refines crude hydrocarbons recovered from the Earth to create hydrocarbon products including: natural gas, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG, or hydrogas), gasoline, kerosene, diesel fuel, and a vast array of synthetic materials such as nylon, plastics and polymers. Crude oil and natural gas occur in tiny openings of buried layers of rock. Occasionally, the crude hydrocarbons literally ooze to the surface in the form of a seep, or spring; but more often, rock layers trap the hydrocarbons thousands of feet below the surface. To harvest the trapped hydrocarbons to the surface, mankind drills wells.

The simplest hydrocarbon is methane (CH4). It has one atom of carbon (C) and four atoms of hydrogen (H). Methane is a gas, under standard conditions of pressure and temperature. Standard pressure is the pressure the atmosphere exerts at sea level, about 14.7 psia (101 kPa). Standard temperature is 60°F (15.6°C). Methane is the primary component in natural gas. Natural gas occurs in buried rock layers usually mixed with other hydrocarbon gases and liquids. It may also contain non-hydrocarbon gases and liquids such as helium, carbon dioxide, nitrogen, water, and hydrogen sulfide. Hydrogen sulfide is toxic and corrosive − it has a detectible sour or rottenegg odor, even in low concentrations. Natural gas that contains hydrogen sulfide is called sour gas. After natural gas is produced or recovered, a gas processing facility removes impurities so consumers can use the gas.

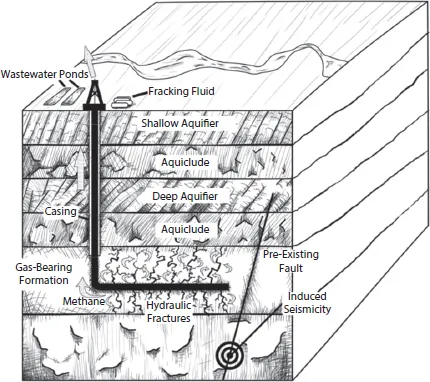

Hydraulic fracturing is a technique used by the oil and gas industry to mine hydrocarbons trapped deep beneath the Earth’s surface. Hydraulic fracturing, also known as “fracking” or fracturing is an industry-wide practice that has received significant attention and increased scrutiny from the media and environmental community. Fracturing involves the injection of water, sand and chemicals under pressure into prospective rock formations to stimulate oil and natural gas production. In recent years there has been a dramatic rise in unconventional natural gas and oil production largely attributable to the application of fracturing technology. The basic technology is comprised of the following. Vertical well bores are drilled thousands of feet into the earth, through sediment layers, the water table, and shale rock formations with the objective of reaching oil and gas deposits. Drilling operations are then angled horizontally, where a cement casing is installed and is intended to serve as a conduit for the massive volume of water, fracking fluid, chemicals and sand needed to fracture the rock and shale. In some cases, prior to the injection of fluids, it is necessary to employ small explosives in order to open up the bedrock. The fractures allow the gas and oil to be removed from the formerly impervious rock formations.

Fracking has technically been in existence for many decades, however, the scale and type of drilling now taking place (i.e., deep fracking) is a new form of drilling and was first used in the Barnett shale of Texas in 1999. Figure 1.1 illustrates the basic principles of the technology.

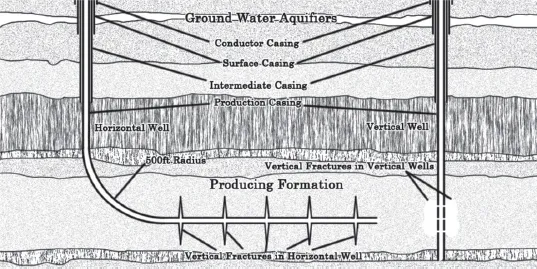

The science and engineering behind the use of horizontal wells is very much an evolving technology. Horizontal wells are viewed by the oil and gas industry as offering benefits that improve the production performance for certain types of producing formations. Horizontal wells allow operators to develop resources with significantly fewer wells than may be required with vertical wells − operators can drill multiple horizontal wells from a single surface location, thereby, reducing the cumulative surface footprint and impact of the development operation. On the other hand, horizontal wells are significantly more expensive to drill and maintain. In some areas, the cost of a horizontal well may be 2−3 times the cost of a vertical well. Horizontal wells are typically drilled vertically to a “kick-off” point where the drill bit is gradually re-oriented from vertical to horizontal. Figure 1.2 is a schematic, which illustrates a vertical and horizontal well for comparison.

In horizontal wells, an “open-hole” completion is an alternative to setting the casing through the producing formation to the total depth of the well. In this case, the bottom of the production casing is installed at the top of the productive formation or open-hole section of the well. In this alternative, the producing portion of the well is the horizontal portion of the hole and it is entirely in the producing formation. In some instances, a short section of steel casing that runs up into the production casing, but not back to the surface, may be installed. Alternatively, a slotted or pre-perforated steel casing may be installed in the open-hole portion. These alternatives are generally referred to by the industry as a “production liner,” and are typically not cemented into place. In the case of an open-hole completion, tail cement is extended above the top of the confining formation (the formation that limits the vertical growth of the fracture).

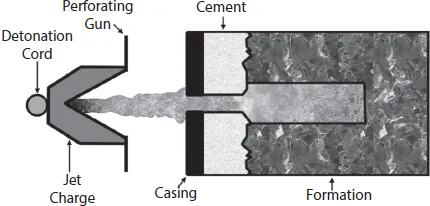

The term reservoir refers to the subsurface hydrocarbon bearing formation. An important term applied in hydraulic fracturing is perforating. A perforation is the hole that is created between the casing or liner into the reservoir. This hole allows communication to the inside of the production casing, and is the hole through which oil or gas is produced. By far the most common perforating method utilizes jet-perforating guns that are loaded with specialized shaped explosive charges. Figure 1.3 illustrates the perforation process. The shaped charge is detonated and a jet of hot, high-pressure gas vaporizes the steel pipe, cement, and formation in its path. The result is an isolated tunnel that connects the inside of the production casing to the formation. The cement isolates these channels or tunnels. The producing zone itself is isolated outside the production casing by the cement above and below the zone.

Hydraulic fracturing is not a new technology − rather its origins go back to as early as the late 1940s as a well stimulation technique. Ultra-low permeability formations such as fine sand and shale tend to have fine grains or limited porosity and few interconnected pores (low permeability). The term permeability refers to the ability for a fluid to flow through a porous rock. In order for natural gas or oil to be produced from low permeability reservoirs, individual molecules of fluid must find their way through a tortuous path to the well. Hydraulic fracturing facilitates the process because without it too little oil and/or gas would be recoverable and the cost to drill and complete the well would be impractical based on the rate of recovery.

The process of hydraulic fracturing increases the exposed area of the producing formation, thus creating a high conductivity path that extends from the wellbore through a targeted hydrocarbon bearing formation over a significant distance − subsequently, hydrocarbons and other fluids can flow more readily from the formation rock, into the fracture, and ultimately to the wellbore. Hydraulic fracturing treatments rely on state-of-the-art software programs and are an integral part of the design and construction of the well. Pretreatment quality control and testing are considered integral actions in producing wells.

During fracking, fluid is pumped into the production casing, through the perforations (or open hole), and into the targeted formation at pressures high enough to cause the rock within the targeted formation to fracture. This is referred to as “breaking down” the formation. As high-pressure fluid injection continues, this fracture can continue to grow, or propagate. The rate at which fluid is pumped must be fast enough that the pressure necessary to propagate the fracture is maintained. This pressure is referred to as the propagation pressure or extension pressure. As the fracture continues to propagate, a proppant (e.g., sand) is added to the fluid. When the pumping is stopped, and the excess pressure is removed, the fracture attempts to close. The proppant serves the purpose of keeping the fracture open, allowing fluids to then flow more readily through this higher permeability fracture.

Some of the fracturing fluid may leave the fracture and enter the targeted formation adjacent to the created fracture (i.e. untreated formation). This phenomenon is known as fluid leak-off. This fluid flows into the micropores of the formation or into existing natural fractures in the formation or into small fractures opened and propagated into the formation by the pressure in the induced fracture. The fracture tends to propagate along the path of least resistance. Since this technology has been practiced for many years, experience allows predictable characteristics or physical properties regarding the path of least resistance for horizontally and vertically formed fractures.

In executing hydraulic fracturing operations, a fluid must be pumped into the well’s production casing at high pressure. It is necessary that production casing has been installed and cemented and that it is capable of withstanding the pressure that it will be subjected to during hydraulic fracture operations. The production casing in some applications is not exposed to high pressure except during hydraulic fracturing. In these cases, a high-pressure “frac string” may be used to pump the fluids into the well to isolate the production casing from the high treatment pressure. Once the hydraulic fracturing oper...