The Agility Factor

Building Adaptable Organizations for Superior Performance

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Agility Factor

Building Adaptable Organizations for Superior Performance

About this book

A research-based approach to achieving long-term profitability in business

What does it take to guarantee success and profitability over time? Authors Christopher G. Worley, a senior research scientist, Thomas D. Williams, an executive advisor, and Edward E. Lawler III, one of the country's leading management experts, set out to find the answer. In The Agility Factor: Building Adaptable Organizations for Superior Performance the authors reveal the factors that drive long-term profitability based on the practices of successful companies that have consistently outperformed their peers. Of the 234 large companies across 18 industries that were studied, there were few companies that delivered sustained performance across the board. The authors found that across industries, the most successful companies were not the "usual suspects" found in the media, but companies who possessed a quiet agility that allowed them to quickly perceive and respond to changes so that they could continue to grow. Agility gives organizations the ability to adapt to fluctuations in the environment, test possible responses, and implement changes quickly. This book offers specific, research-based case studies to help organizational leaders use agility to achieve sustained profitability and performance while also becoming more adaptable to a changing marketplace.

For executives, leaders, consultants, board members and all those responsible for the long-term health of organizations, this insightful guide outlines:

- The components of agility for business organizations

- How to successfully build agility within an organization

- How agility has its foundation in good management practices

- How to use agility to gain a competitive advantage in the marketplace

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Searching for Sustained Performance

Surviving versus Thriving

The Old Way of Defining Sustained Performance

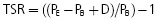

Shareholder Returns

- PE is the price per share at the end of the period;

- PB is the price per share at the beginning of the period; and

- D is dividends per share paid in the period.

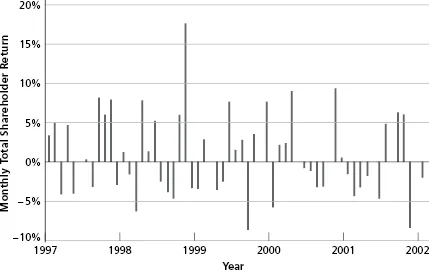

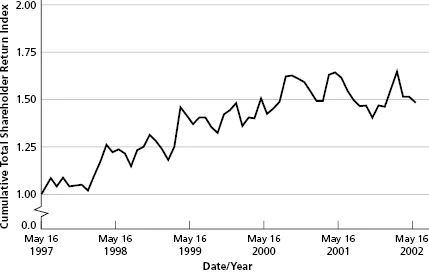

- CTSRt is the cumulative TSR in time period t;

- CTSRt−1 is the cumulative TSR in time period t − 1 (the prior period); and

- TSRt is the total shareholder return in time period t (as calculated above). The monthly cumulative TSR for ExxonMobil from May 1997 to June 2002 is shown in Exhibit 1.3.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- More praise for The Agility Factor

- Series page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Foreword

- Preface

- CHAPTER 1: Searching for Sustained Performance

- CHAPTER 2: Organizing for Agility

- CHAPTER 3: Strategizing and Perceiving

- CHAPTER 4: Testing and Implementing

- CHAPTER 5: Transforming to Agility

- Afterword: Some Reflections on Agility

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- End User License Agreement