eBook - ePub

Advanced Materials for Agriculture, Food, and Environmental Safety

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Advanced Materials for Agriculture, Food, and Environmental Safety

About this book

The book focuses on the role of advanced materials in the food, water and environmental applications. The monitoring of harmful organisms and toxicants in water, food and beverages is mainly discussed in the respective chapters. The senior contributors write on the following topics:

- Layered double hydroxides and environment

- Corrosion resistance of aluminium alloys of silanes

- New generation material for the removal of arsenic from water

- Prediction and optimization of heavy clay products quality

- Enhancement of physical and mechanical properties of fiber

- Environment friendly acrylates latices

- Nanoparticles for trace analysis of toxins

- Recent development on gold nanomaterial as catalyst

- Nanosized metal oxide based adsorbents for heavy metal removal

- Phytosynthesized transition metal nanoparticles- novel functional agents for textiles

- Kinetics and equilibrium modeling

- Magnetic nanoparticles for heavy metal removal

- Potential applications of nanoparticles as antipathogens

- Gas barrier properties of biopolymer based nanocomposites: Application in food packing

- Application of zero-valent iron nanoparticles for environmental clean up

- Environmental application of novel TiO2 nanoparticles

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Advanced Materials for Agriculture, Food, and Environmental Safety by Ashutosh Tiwari, Mikael Syväjärvi, Ashutosh Tiwari,Mikael Syväjärvi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technik & Maschinenbau & Werkstoffwissenschaft. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

FUNDAMENTAL METHODOLOGIES

Chapter 1

Layered Double Hydroxides and the Environment: An Overview

Abstract

Due to their versatility, hundreds of millions of tons of clay minerals currently find applications not only in ceramics, building materials, paper coating and fillings, drilling muds, foundry molds, pharmaceuticals, etc., but also as adsorbents, catalysts or catalyst supports, ion exchangers, etc., depending on their specific properties. There are two broad classes of clays: Cationic clays (or clay minerals), widespread in nature, and Anionic clays (or layered double hydroxides), more rare in nature but relatively simple and inexpensive to synthesize on a laboratory or industrial scale. Cationic clays have negatively charged alumina-silicate layers with small cations in the interlayer space to balance the charge, while anionic clays have positively charged brucite type metal hydroxide layers with balancing anions and water molecules located interstitially. The layered double hydroxides (LDHs) belonging to the general class of anionic clay minerals can be of both synthetic and natural origin. Also known as hydrotalcite-like compounds (HTLCs), these materials are interesting because their layer cations can be changed among a wide selection, and the interlayer anion can also be freely chosen. Like cationic clays, they can be pillared and can exchange interlayer species, thus increasing applications and making new routes to synthesize the derivatives.

This chapter deals with the brief history of layered double hydroxides, their structure, properties, synthesis by different methods and characterization, along with their applications mainly in the environmental field.

Keywords: Layered double hydroxides, anionic clays, cationic clays, brucite, interlayer species, heavy metals, dyes, greenhouse gases, surfactants

1.1 Introduction

Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) have been known for a very long time. Around 1842, naturally forming LDHs minerals were discovered in Sweden. Crushing these minerals leads to a white powder similar to talc. These materials were first synthesized by a German scientist, W. Feithnecht (1942), through reaction between dilute solutions of metals with bases, which he named “doppelschichtstrukturen” or double-sheet structure. The LDHs are also known as hydrotalcite-like compounds (HTLCs). Hydrotalcite (HT) is a hydroxycarbonate of magnesium and aluminium which occurs in nature in foliated and contorted plates or fibrous masses.

During the discovery of hydrotalcite another hydroxycarbonate of magnesium and iron was found, which was called pyroaurite. Pyroaurite was later recognized to be isostructural with hydrotalcite and other minerals containing different elements, all of which were recognized as having similar features. Hydrotalcites have been studied for their use as catalysts and precursors to various other catalysts as early as 1970 [1, 2].

Allman and Taylor studied single crystal X-ray diffraction on mineral samples which revealed the main structural entities of LDHs and disproved Feitknecht’s theory. These studies showed that the two cations were in fact located in a single layer and the interlayers were composed of water and carbonate ions. Although the main entities of LDHs have been elucidated, Evans and Slade [3] have suggested that several intrinsic details still remain to be fully understood. These include the possible stoichiometric range and composition, and the position and arrangement of metals within each cationic layer. Prior to the study by Evans and Slade, Miyata and Okada [4–6] described many structural features of LDHs/HTLCs which have different guest anions.

Layered double hydroxide materials appear in nature and can be readily prepared in the laboratory. In nature they are formed from the weathering of basalts [7, 8] or precipitation [9] in saline water. All natural LDH minerals have a structure similar to hydrotalcite, which has the formula [Mg6Al2 (OH)16] CO3. 4H2O. Unlike clays, however, layered double hydroxides are not discovered in large, commercially exploitable deposits [9]. The LDHs have been prepared using many combinations of divalent and trivalent cations including magnesium, aluminium, zinc, nickel, chromium, iron, copper, indium, gallium and calcium [10–31].

1.2 Structure of Layered Double Hydroxides

Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) are also known as hydrotalcite-like compounds (due to their structural similarities to that mineral) or anionic clays and host-guest layered materials [1, 3, 32–35], which are quite rare in nature. Most LDHs are synthetic phases and their structure resembles the naturally occurring mineral hydrotalcite [Mg6Al2(OH)16] CO3. 4H2O, having the general formula of [M(II)1−x M (III)x (OH)2] (Yn−)x/n. YH2O, where, M(II), M(III) = divalent and trivalent metals respectively, 0.2 < x < 0.33, and Yn− = the exchangeable anions between the layers [10, 36, 37].

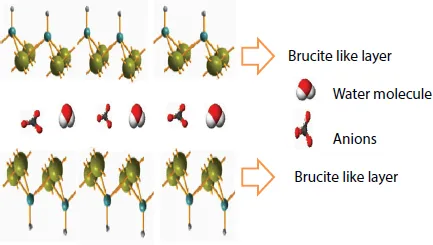

The basic layer structure of LDHs is based on brucite [Mg (OH)2], typically associated with small polarizing cations and polarizable anions. It consists of magnesium ions surrounded approximately octahedrally by hydroxide ions. These octahedral units form infinite layers by edge-sharing with the hydroxide ions sitting perpendicular to a plane of the layers. The layers then stack on top of one another to form a three-dimensional structure.

When Mg2+ is replaced by a trivalent cation similar in radius, an overall positive charge results in the hydroxyl sheets and counter balance is provided by carbonate ions which are positioned within the hydroxyl interlayer. In addition to carbonate ions, water molecules are found in the interlayer gallery. The nature of the interlayer anion and the extent of hydration often determine the layer spacing between each brucite-like sheet [38]. The brucite-like sheets may occur in two different symmetries, namely rhombohedral and hexagonal. In nature, the rhombohedral symmetry is widespread. However, in mineral samples, the hexagonal symmetry is seen to favor the interior of the crystallite samples, while the rhombohedral symmetry is found on the exterior. This is a result of cooling during crystallite transformation, in which the extrerior surface of the crystallite cools much quicker than the interior and hence the interior hexagonal form cannot transform due to a higher energy transformation barrier at lower temperature. From these observations, it has been deduced that the hexagonal symmetry is favored by high temperature [1, 4]. Naturally occurring minerals that exhibit a LDH structure include manasseite, pyroaurite, sjogrenite, bar-betonite, takovite, reevesite, desautelsite and stichtite. They differ from one another in the stacking arrangement of the octahedral layers [1, 39].

Conventionally synthesized LDHs are strongly hydrophilic materials, either amorphous or microcrystalline with hexagonal habit, with the dominant faces developed parallel to the metal hydroxide layers. Adjacent layers are tightly bound to each other. Figure 1.1 shows the structure of layered double hydroxides.

Figure 1.1 Structure of layered double hydroxide (LDHs).

One of the advantages of LDHs among layered materials is the great number of possible compositions and metal–anion combinations that can be synthesized. Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) have high charge density. The charge density is dependent on the metal ratio. Since it comprises a divalent and trivalent metal cation, their ratio affects charge density of the layers. A lower divalent/trivalent ratio results in a higher charge density.

1.3 Properties of Layered Double Hydroxides

Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) display unique physical and chemical properties close to those of clay minerals. Some interesting properties of these materials summarized by Del Hoyo [40] are:

- High specific surface area (100±300 m2/g)

- Memory effect

- Anion exchange capacities

- Synergistic effects

The LDHs exhibit anion mobility, surface basicity and anion exchangeability due to their positively charged layered structure. The anions and water, which fill the interlayer space, are labile. Therefore a variety of inorganic and organic anions can be intercalated in the interlayer of LDHs through anion exchange reactions [33]. The mixed metal oxides obtained on calcination of LDH usually exhibit properties such as high surface area, surface basicity and formation of homogeneous mixture with small crystallite size when heated to higher temperature [1]. The LDHs as well as the oxides obtained from them exhibit excellent catalytic activity. Structure reconstruction, or so called “memory effect,” is another important property of LDHs which is unique to this class of layered solids. Structure reconstruction is usually achieved by first decomposing the LDH at suitable high temperature followed by treating the resultant mixed metal oxides with a solution containing a suitable anion [41]. These materials have a high capacity for adsorbing anions as well as cations [38, 42]. Magnetic properties of the LDHs depend on the space between the layers. This space can be adjusted by insertion of organic anions with different chain lengths. This suggests that these hybrid materials would work as tunable magnets [43]. The LDHs intercalated with long-chain surfactant molecules such as dodecyl sulphate have the ability to swell in organic solvents. This property of delamination is exploited in the preparation of monolayers, which are used extensively in the synthesis of nanohybrids and nanocomposites [44].

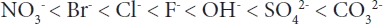

The interlayer anions present in LDHs can be exchanged by other anions. The order of preference for some common inorganic anions is as follows:

NO3− is an anion which can be easily replaced by a more strongly held one like CO32−. Therefore when preparing precursor for interaction, nitrate salts are preferred ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Preface

- Part 1: Fundamental Methodologies

- Part 2: Inventive Nanotechnology

- Index