- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Using the well-honed tools of nanotechnology, this book presents breakthrough results in soft matter research, benefitting from the synergies between the chemistry, physics, biology, materials science, and engineering communities.

The team of international authors delves beyond mere structure-making and places the emphasis firmly on imparting functionality to soft nanomaterials with a focus on devices and applications. Alongside reviewing the current level of knowledge, they also put forward novel ideas to foster research and development in such expanding fields as nanobiotechnology and nanomedicine. As such, the book covers DNA-induced nanoparticle assembly, nanostructured substrates for circulating tumor cell capturing, and organic nano field effect transistors, as well as advanced dynamic gels and self-healing electronic nanodevices.

With its interdisciplinary approach this book gives readers a complete picture of nanotechnology with soft matter.

The team of international authors delves beyond mere structure-making and places the emphasis firmly on imparting functionality to soft nanomaterials with a focus on devices and applications. Alongside reviewing the current level of knowledge, they also put forward novel ideas to foster research and development in such expanding fields as nanobiotechnology and nanomedicine. As such, the book covers DNA-induced nanoparticle assembly, nanostructured substrates for circulating tumor cell capturing, and organic nano field effect transistors, as well as advanced dynamic gels and self-healing electronic nanodevices.

With its interdisciplinary approach this book gives readers a complete picture of nanotechnology with soft matter.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Chemical Reactions for the Synthesis of Organic Nanomaterials on Surfaces

Hong-Ying Gao, Oscar Díaz Arado, Harry Mönig, and Harald Fuchs

1.1 Introduction

The bottom-up growth of covalently connected organic networks is a fascinating approach for the development of new functional nanomaterials with tunable mechanical and optoelectronic properties [1–5]. Hereby, organic molecules are the building blocks, which can be deposited on a substrate by evaporation under ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) conditions or by solution growth in liquid environments. By the proper design of the precursor molecules and by controlling the parameters such as deposition rates, concentrations, and substrate temperature or irradiation, chemical reactions can be induced. This can lead to the formation of either conjugated polymers or 2D covalently connected networks [6–8]. The structural and optoelectronic properties of these products can be adjusted by the manifold possibilities of organic chemistry, which allows tailoring the reactive end groups, and the geometry as well as the electronic properties of the reactants. Following this idea, nanoscale devices ranging from simple wires to transistors, capacitors, or solar cells can be envisioned. Although recent years have shown significant progress in this field, there are only a few established on-surface reaction mechanisms that actually lead to covalent coupling directly at surfaces. Therefore, there are still considerable scientific challenges at play, making it a current hot topic in nanotechnology [2,5,6].

To study the chemical processes involved in the synthesis of such materials, experimental techniques with high lateral resolution are particularly desirable. Therefore, scanning probe microscopy and in particular scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) and noncontact atomic force microscopy (NC-AFM) have become the standard characterization tools providing direct insight into reaction mechanisms. These techniques offer topographic and electronic information of single molecules and on-surface chemical processes with high resolution [9–11], and the probe tip itself can be used to trigger chemical reactions [12–14] or to manipulate molecular species at surfaces [15,16]. Furthermore, both STM and NC-AFM experiments can be performed under different environmental conditions, such as in UHV, in liquids, or in gaseous environments, providing further versatility to the targeted experiments. Many studies also rely on complementary experimental techniques such as X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) or temperature-programmed desorption (TPD). From the theory side, density functional theory (DFT) is applied to describe adsorption geometries and chemical processes that take place on various substrates.

In the following, the so far established on-surface reaction mechanisms are reviewed, which potentially can be utilized for the bottom-up growth of covalently connected organic networks. Other approaches where surfaces are exclusively involved to catalyze reactions and where the products do not stay on the surface are not considered in this chapter. Besides a general overview of the various reaction types, we present a compilation of the results obtained by our group at the University of Münster, which contributed to this exciting research field.

1.1.1 Ullmann Coupling

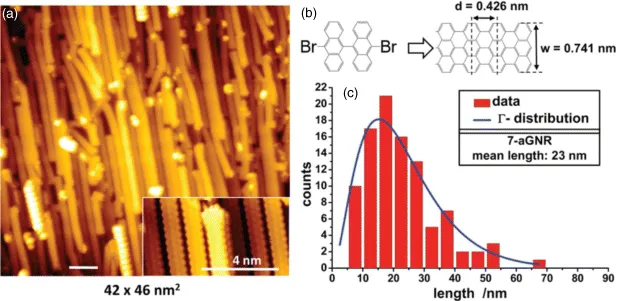

This particular reaction is the most studied one in the recent years. It involves the thermal activation of precursor molecules with halogenated moieties after or during deposition on a substrate, which, by the supply of heat, leads to the formation of C–C bonds between the radicalized reactants. This reaction has been performed mostly on metal substrates. However, recently it has been shown to also proceed on insulators [17], which represents a significant step forward toward potential applications of the Ullmann coupling mechanism. The halogen specie mostly studied is bromine [18–24], although successful covalent coupling after scission of terminal iodine [19,25–27] and chlorine [17,28] has also been reported. The difference in activation temperature for the different carbon–halogen species has allowed to hierarchically control the formation of two-dimensional networks [19,24]. Another interesting nanomaterial with functional electronic properties developed with this method is based on graphene nanoribbons. These are obtained by a two-step reaction sequence where after initial on-surface Ullmann coupling, a further annealing step at a higher temperature leads to cyclodehydrogenation of adjacent aromatic species [23,29]. In particular, graphene nanoribbons were also successfully grown on a stepped Au(788) surface, which form well-defined (111) terraces with a width of about 3.8 nm along the [01–1] direction (Figure 1.1). This allows to gain control over the orientation of the nanoribbons, which predominantly grow along the terraces. High-resolution direct and inverse photoemission experiments of occupied and unoccupied states allowed to determine the energetic position and momentum dispersion of electronic states, which showed a bandgap of several electronvolts for different types of graphene nanoribbons [23,29].

Figure 1.1 (a) STM image of spatially aligned graphene nanoribbons on a Au(788) surface. (b) After initial Ullmann coupling at a substrate temperature of 440–470 K, an additional heating step at 590 K results in a dehydrogenation process leading to the formation of the nanoribbons. (c) Statistical distribution of the ribbon length. (Reprinted figure with permission from [29]. Copyright (2012) by the American Physical Society.)

It has been demonstrated that in general it is possible to achieve covalent bonding between organic molecules and metal atoms on surfaces [11,30]. Therefore, there are also efforts to not directly bind the organic building blocks for supramolecular structures, but instead use metal atoms to mediate the coupling. Following this approach under UHV conditions, covalent bonding between tetracyanobenzene molecules and Mn atoms was accomplished to form Mn-phthalocyanine [31]. In another study, strong bonds between metal atoms and dehalogenated reactants have been shown to play an important role in the on-surface Ullmann coupling, stabilizing two-dimensional networks [24]. Furthermore, an on-surface chemical reaction between copper ions and quinone ligands at the liquid/solid interface of a Au(111) surface has been shown to successfully form two-dimensional metal–organic polymers [32].

The results on metal–organic materials lead to further developments, which use Ullmann coupling to form gold–organic hybrids, where chemical bonding between organic precursor molecules is mediated by bonding to a substrate gold atom. With this approach, the on-surface synthesis of gold–organic linear polymers by the dehalogenation of chloro-substituted perylene-3,4,9,10-tetracarboxylic acid bisimides (PBIs) was accomplished on the Au(111) and Au(100) surfaces [17,28]. Figure 1.2a shows an STM image after depositing the PBIs at room temperature on a Au(111) surface, leading to a self-assembled monolayer of the unreacted molecules. The STM contrast features a combination of two small bumps and a big rod corresponding to the short alkyl chains and the aromatic core of the PBI molecule, respectively. The bright spots on both sides of the core correspond to the twisted two chlorine atoms. Linear molecular chains were formed via depositing the precursor molecules on a 490 K preheated Au(111) surface at a deposition rate of about 0.1 monolayer per hour. Figure 1.2b is a representative STM image of the reaction products, in which polymers with a length of up to 70 nm can be observed. Interestingly, the orientation of the molecular chains was found mainly along 〈110〉 directions on the Au(111) surface. A high-resolution STM image of such a polymer is shown in Figure 1.2c, with its proposed chemical structure shown in Figure 1.2d. The measured periodic distance along the chain is (0.83 ± 0.04) nm, which matches well with the theoretical distance of 0.82 nm as determined by DFT calculations. Further experiments with the PBI deposited on the reconstructed Au(100) surface showed that on this surface the polymerization occurs exclusively along the [011] direction [28]. Further DFT calculations on a simplified model system confirmed that the reaction mechanism involves an intermediate state ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title Page

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Chemical Reactions for the Synthesis of Organic Nanomaterials on Surfaces

- Chapter 2: Self-Assembly of Organic Molecules into Nanostructures

- Chapter 3: Supramolecular Nanotechnology: Soft Assembly of Hard Nanomaterials

- Chapter 4: Nanoparticles: Important Tools to Overcome the Blood–Brain Barrier and Their Use for Brain Imaging

- Chapter 5: Organic Nanophotonics: Controllable Assembly of Optofunctional Molecules toward Low-Dimensional Materials with Desired Photonic Properties

- Chapter 6: Functional Lipid Assemblies by Dip-Pen Nanolithography and Polymer Pen Lithography

- Chapter 7: PEG-Based Antigen-Presenting Cell Surrogates for Immunological Applications

- Chapter 8: Soft Matter Assembly for Atomically Precise Fabrication of Solid Oxide

- Chapter 9: Conductive Polymer Nanostructures

- Chapter 10: DNA-Induced Nanoparticle Assembly

- Chapter 11: Nanostructured Substrates for Circulating Tumor Cell Capturing

- Chapter 12: Organic Nano Field-Effect Transistor

- Chapter 13: Advanced Dynamic Gels

- Chapter 14: Micro/Nanocrystal Conversion beyond Inorganic Nanostructures

- Chapter 15: Self-Healing Electronic Nanodevices

- Index

- EULA

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Soft Matter Nanotechnology by Xiaodong Chen,Harald Fuchs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.