![]()

Part 1

CARBON NANOMATERIALS

![]()

Chapter 1

Easy and Large-Scale Synthesis of Carbon Nanotube-Based Adsorbents for the Removal of Arsenic and Organic Pollutants from Aqueous Solutions

Fei Yu1 and Jie Ma2*

1College of Chemistry and Environmental Engineering, Shanghai Institute of Technology, Shanghai, P. R. of China

2State Key Laboratory of Pollution Control and Resource Reuse, College of Environmental Science and Engineering, Tongji University, Shanghai, P. R. of China

Abstract

The as-prepared carbon nanotubes (APCNTs) synthesized by chemical vapor deposition method usually contained carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and quantities of iron nanoparticles (INP)–encapsulated carbon shells. The traditional research mainly focuses on how to remove the INPs using various chemical and physical purification methods. In this chapter, we have synthesized many kinds of CNTs-based adsorbents based on the aforementioned iron/carbon APCNT composites without purification, which can be used for the removal of arsenic and organic pollutants from aqueous solutions with excellent adsorption properties. This synthesis method is applicable to as-prepared single-walled CNTs and multi-walled CNTs containing metal catalytic particles (e.g., Fe, Co, Ni), and the resulting material may find direct applications in environment, energy storage, catalysis, and many other areas. Results of this work are of great significance for large-scale practical applications of APCNTs without purification.

Keywords: Magnetic carbon nanotubes, arsenic, organic pollutants, adsorption

1.1 Introduction

Magnetic carbon nanotubes (MCNTs) are of intense research interests because of their valuable applications in many areas such as magnetic data storage, magnetic field screening, and signal transmission [1]. Synthetic methods of MCNTs include chemical and physical techniques. For instance, magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), such as cobalt, iron, or nickel and their oxide NPs, can be encapsulated by carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [2, 3]. In addition, MNPs could be deposited on the external surface of CNTs [4, 5]. However, existing synthesis methods may have the following critical disadvantages: firstly, the as-prepared carbon nanotubes (APCNTs) are usually purified using strong acids to remove metal particles and carbonaceous byproducts [6], and then MNPs are loaded on the wall of purified CNTs. As a result, the synthesis process is expensive and time consuming with a low yield. Secondly, uncovered MNPs may agglomerate when a magnetic field is applied. Thirdly, bare MNPs could be oxidized in air or erode under acidic conditions [7]. These issues may ultimately hinder widespread practical applications of the MCNTs composite. In recent years, CNTs could be produced in ton-scale quantities per year with high quality. However, APCNTs often contain a large fraction of impurities, including small catalytic metal particles and carbonaceous byproducts such as fullerenes, amorphous, or graphitic carbon particles. The current research direction in this area mainly focuses on the purification of APCNTs through physical separation [8], gas-phase oxidation [9], and liquid-phase oxidation [6], aiming at applications of purified CNTs. However, these purification processes are complex, time consuming, and environmentally unfriendly. Hence, the existing approach is suitable for fundamental research but not for large-scale applications of MCNTs.

To overcome the aforementioned issues, we herein report several new-typed methods to produce MCNTs using APCNTs. We show that MCNTs can be well dispersed in water with excellent magnetic properties. This facile synthesis method has the following advantages: firstly, metal nanoparticles in the APCNTs can be utilized directly without any purification treatment; secondly, the carbon shells provide an effective barrier against oxidation, acid dissolution, and movement of MNPs and thus ensure a long-term stability of MNPs. MCNTs were used as adsorbents for the removal of environmental pollutants in aqueous solutions, and arsenic and organic pollutants were chosen as target pollutants. MCNTs exhibit excellent adsorption and magnetic separation properties. After adsorption, the MCNTs adsorbents could be effectively and immediately separated using a magnet, which reduces potential risks of CNTs as another source of environmental contaminant. Therefore, MCNTs can be used as a promising magnetic adsorbent for the removal of arsenic and organic pollutants from aqueous solutions.

1.2 Removal of Arsenic from Aqueous Solution

1.2.1 Activated Magnetic Carbon Nanotube

1.2.1.1 Synthesis Method

The APCNTs were prepared using a chemical vapor deposition(CVD) method [10]. Ethanol was used as the carbon feedstock, ferrocene was used as the catalyst, and thiophene was used as the growth promoter. Argon flow was introduced in the quartz tube in order to eliminate oxygen from the reaction chamber. The ethanol solution dissolved with ferrocene and thiophene was supplied by an electronic squirming pump and sprayed through a nozzle with an argon flow. After several hours of pyrolysis, the supply of ethanol was terminated, and the APCNTs were collected from a collecting unit connected to the quartz tube.

The Magnetic iron oxide/CNTs(MI/CNTs) composites were prepared by an alkali-activated method using APCNTs. The APCNTs were prepared by the catalytic chemical vapor deposition method [10]. In a typical synthesis, APCNTs and KOH powder were mixed in a stainless steel vessel in an inter-gas atmosphere. The weight ratio of KOH to APCNTs was 1:4. The APCNTs and KOH powder were mixed for 10 min using a mortar, which resulted in a uniformly powder mixture. The mixture was then heated to 1023 K for 1 h under flowing argon in a horizontal tube furnace, washed in the deionized water, and then dried.

1.2.1.2 Characterization of Adsorbents

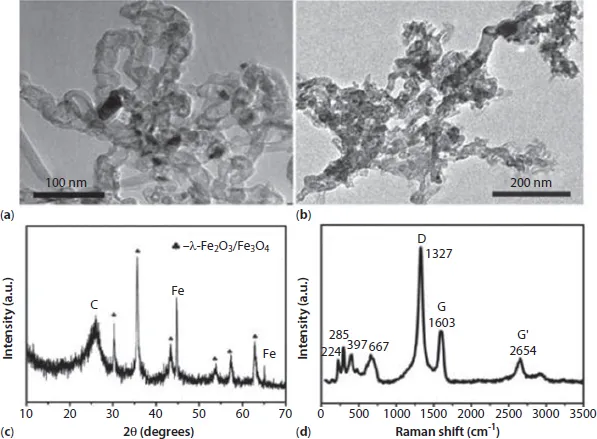

Figure 1.1a displays the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of APCNTs; the diameter of APCNTs is about 20–30 nm and the length is about 1 μm. After the activation treatment, the structure of APCNTs has been clearly modified, and the length of MI/CNTs is obviously shortened. Furthermore, part of the hollow tubular structure is destroyed, large quantities of defects are produced, and many flaky apertures are generated on the surface, as shown in Figure 1.1b. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of MI/CNT hybrids indicated that the MI/CNTs were a mixture of two/three phases: γ-Fe2O3/Fe3O4 and CNTs. Well-resolved diffraction peaks reveal the good crystallinity of γ-Fe2O3/Fe3O4 specimens; no peaks corresponding with impurities were detected. Peaks of C with relatively high intensity and symmetry are clearly observed in Figure 1.1c. This observation suggests the graphite structure remained, even after strong activation reaction; therefore, we may conclude that MI/CNT heterostructures were formed using the KOH activation method.

The Raman spectrum of MI/CNTs is shown in Figure 1.1d. For MI/CNTs, the remaining peaks at 224 and 285 cm–1 are assigned to the A1g and Eg modes of α-Fe2O3, the peak at 397 cm–1 is assigned to the T2g modes of λ-Fe2O3, and the peak at 667 cm–1 is assigned to the A1g modes of Fe3O4 [11]. The results indicate that magnetic iron oxide in MI/CNTs may be a mixture phase composed of α-Fe2O3, λ-Fe2O3, and Fe3O4. The G peak at 1585 cm–1 is related to E2g graphite mode [12–14]. The D-line at ~1345 cm–1 is induced by defective structures. The intensity ratio of the G and D peaks (IG/ID) is an indicator for estimating the structure quality of CNTs, as shown in Figure 1.1d, which suggests the structure of the CNTs was destroyed after the KOH activation process.

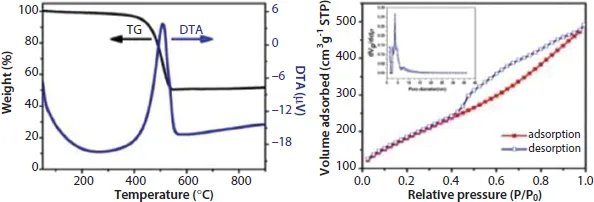

In Figure 1.2a, the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the MI/CNTs exhibits two main weight-loss regions. MI/CNTs are considerably stable and show a little weight loss close to 5% below 200 °C in the first region, which can be attributed to the evaporation of adsorbed water and the elimination of carboxylic groups and hydroxyl groups on the MI/CNTs. The rapid weight-loss region can be due to the oxidation of CNTs. It is clearly seen that the main thermal events temperature was at ~500 °C; however, the thermal events temperature is so high that MI/CNTs could readily meet the application needs of adsorbent in water treatment.

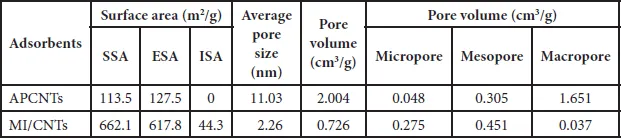

The specific surface area (SSA) and pore size characterization of MI/CNTs were performed by nitrogen (77.4 K) adsorption/desorption experiments with density functional theory (DFT) methods [15], as shown in Figure 1.2b. The MI/CNTs had a high SSA of ~662.1 m2/g (calculated in the linear relative pressure range from 0.1 to 0.3). The SSA of MI/CNTs is drastically increased by ~5 times than APCNTs; such increases correspond with a decrease in mean pore diameter from ~11.03 to ~2.26 nm (BJH). After alkalis activation treatment, not only the tube tip was opened, but also large quantities of new micropore structures with small sizes were produced. This implies that the MI/CNTs possess more small pores after the present activation treatment and thus could lead to a higher SSA. The detailed features of the pore distribution analysis are presented in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Physical properties of APCNTs and MI/CNTs.

Figure 1.2b displays the results of the cumulative pore volume (PV) and pore size analysis from nitrogen adsorption by applying a hybrid Non-local Density Functional Theory (NLDFT) kernel, assuming a slitshape pore for the micropores and a cylindrical pore for the mesopores. The obtained pore size/PV distribution indicates this MI/CNTs sample is distinctive from APCNTs. Compared with APCNTs, the total PV of MI/CNTs decreased due to the disappearance of maro pores. The meso-PV and micro-PV of MI/CNTs improved by almost ~1.48 and ~5.73 times than that of APCNTs. The stronger peak of pore distribution of MI/CNTs exists at ~2 nm, which indicates the presence of plenty of micropores after the alkalis activation treatment.

The composition of MI/CNTs was further determined by XPS, as shown in Figure 1.3. Typical XPS survey scans ...