![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to Dependable Distributed Computing

Distributed systems bring many benefits to us, for example, we can share resources such as data storage and processing cycles much more easily; we can collaborative on projects efficiently even if the team members span across the planet; we can solve challenging problems by utilizing the vast aggregated computing power of large scale distributed systems. However, if not designed properly, distributed systems may appear to be less dependable than standalone systems. As Leslie Lamport pointed out: “You know you have one (a distributed system) when the crash of a computer you’ve never heard of stops you from getting any work done” [9]. In this book, we introduce various dependability techniques that can be used to address the issue brought up by Lamport. In fact, with sufficient redundancy in the system, a distributed system can be made significantly more dependable than a standalone system because such a distributed system can continue providing services to its users even when a subset of its nodes have failed.

In this chapter, we introduce the basic concepts and terminologies of dependable distributed computing, and outline the primary approaches to achieving dependability.

1.1 Basic Concepts and Terminologies

The term “dependable systems” has been used widely in many different contexts and often means different things. In the context of distributed computing, dependability refers to the ability of a distributed system to provide correct services to its users despite various threats to the system such as undetected software defects, hardware failures, and malicious attacks.

To reason about the dependability of a distributed system, we need to model the system itself as well as the threats to the system clearly [2]. We also define common attributes of dependable distributed systems and metrics on evaluating the dependability of a distributed system.

1.1.1 System Models

A system is designed to provide a set of services to its users (often referred to as clients). Each service has an interface that a client could use to request the service. What the system should do for each service is defined as a set of functions according to a functional specification for the system. The status of a system is determined by its state. The state of a practical system is usually very complicated. A system may consist of one or more processes spanning over one or more nodes, and each process might consist of one or more threads. The state of the system is determined collectively by the state of the processes and threads in the system. The state of a process typically consists of the values of its registers, stack, heap, file descriptors, and the kernel state. Part of the state might become visible to the users of the system via information contained in the responses to the users’ requests. Such state is referred to as external state and is normally an abstract state defined in the functional specification of the system. The remaining part of the state that is not visible to users is referred to as internal state. A system can be recovered to where it was before a failure if its state was captured and not lost due to the failure (for example, if the state is serialized and written to stable storage).

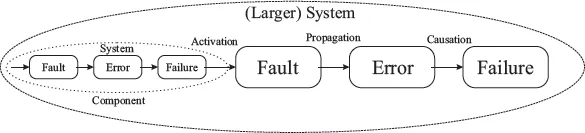

From the structure perspective, a system consists of a one or more components (such as nodes or processes), and a system always has a boundary that separates the system from its environment. Here environment refers to all other systems that the current system interact with. Note that what we refer to as a system is always relative with respect to the current context. A component in a (larger) system by itself is a system when we want to study its behavior and it may in turn have its own internal structures.

1.1.2 Threat Models

Whether or not a system is providing correct services is judged by whether or not the system is performing the functions defined in the functional specification for the system. When a system is not functioning according to its functional specification, we say a service failure (or simply failure) has occurred. The failure of a system is caused by part of its state in wrong values, i.e., errors in its state. We hypothesize that the errors are caused by some faults [6]. Therefore, the threats to the dependability of a system are modeled as various faults.

A fault might not always exhibit itself and cause error. In particular, a software defect (often referred to as software bug) might not be revealed until the code that contains the defect is exercised when certain condition is met. For example, if a shared variable is not protected by a lock in a multithreaded application, the fault (often referred to as race condition) does not exhibit itself unless there are two or more threads trying to update the shared variable concurrently. As another example, if there is no boundary check on accessing to an array, the fault does not show up until a process tries to access the array with an out-of-bound index. When a fault does not exhibit itself, we say the fault is dormant. When certain condition is met, the fault will be activated.

When a fault is activated, initially the fault would cause an error in the component that encompasses the defected area (in programming code). When the component interacts with other components of the system, the error would propagates to other components. When the errors propagate to the interface of the system and render the service provided to a client deviate from the specification, a service failure would occur. Due to the recursive nature of common system composition, the failure of one system may cause a fault in a larger system when the former constitutes a component of the latter, as shown in Figure 1.1. Such relationship between fault, error, and failure is referred to as “chain of threats” in [2]. Hence, in literature the terms “faults” and “failures” are often used interchangeably.

Of course, not all failures can be analyzed with the above chain of threats. For example, a power outage of the entire system would immediately cause the failure of the system.

Faults can be classified based on different criteria, the most common classifications include:

Based on the source of the faults, faults can be classified as:

– Hardware faults, if the faults are caused by the failure of hardware components such as power outages, hard drive failures, bad memory chips, etc.

– Software faults, if the faults are caused by software bugs such as race conditions and no-boundary-checks for arrays.

– Operator faults, if the faults are caused by the operator of the system, for example, misconfiguration, wrong upgrade procedures, etc.

Based on the intent of the faults, faults can be classified as:

– Non-malicious faults, if the faults are not caused by a person with malicious intent. For example, the naturally occurred hardware faults and some remnant software bugs such as race conditions are non-malicious faults.

– Malicious faults, if the faults are caused by a person with intent to harm the system, for example, to deny services to legitimate clients or to compromise the integrity of the service. Malicious faults are often referred to as commission faults, or Byzantine faults [5].

Based on the duration of the faults, faults can be classified as:

– Transient faults, if such a fault is activated momentarily and becomes dormant again. For example, the race condition might often show up as transient fault because if the threads stop accessing the shared variable concurrently, the fault appears to have disappeared.

– Permanent faults, if once a fault is activated, the fault stays activated unless the faulty component is repaired or the source of the fault is addressed. For example, a power outage is considered a permanent fault because unless the power is restored, a computer system will remain powered off. A specific permanent fault is the (process) crash fault. A segmentation fault could result in the crash of a process.

Based on how a fault in a component reveals to other components in the system, faults can be classified as:

– Content faults, if the values passed on to other components are wrong due to the faults. A faulty component may always pass on the same wrong values to other components, or it may return different values to different components that it interacts with. The latter is specifically modeled as Byzantine faults [5].

– Timing faults, if the faulty component either returns a reply too early, or too late alter receiving a request from another component. An extreme case is when the faulty component stops responding at all (i.e., it takes infinite amount of time to return a reply), e.g., when the component crashes, or hangs due to an infinite loop or a deadlock.

Based on whether or not a fault is reproducible or deterministic, faults (primarily software faults) can be classified as:

– Reproducible/deterministic faults. The fault happens deterministically and can be easily reproduced. Accessing a null pointer is an example of deterministic fault, which often would lead to the crash of the system. This type of faults can be easily identified and repaired.

– Nondeterministic faults. The fault appears to happen nondeterministically and hard to reproduce. For example, if a fault is caused by a specific interleaving of several threads when they access some shared variable, it is going to be hard to reproduce such a fault. This type of software faults is also referred to as Heisenbugs to highlight their uncertainty.

Given a number of faults within a system, we can classify them based on their relationship:

– Independent faults, if there is no causal relationship between the faults, e.g., given fault A and fault B, B is not caused by A, and A is not caused by B.

– Correlated faults, if the faults are causally related, e.g., given fault A and fault B, either B is caused by A, or A is caused by B. If multiple components fail due to a common reason, the failures are referred to as common mode failures.

When the system fails, it is desirable to avoid catastrophic consequences, such as the loss of life. The consequence of the failure of a system can be alleviated by incorporating dependability mechanisms into the system such that when it fails, it stops responding to requests (such systems are referred to as fail-stop systems), if this is impossible, it returns consistent wrong values instead of inconsistent values to all components that it may interact with. If the failure of a system does not cause great harm either to human life or to the environment, we call such as system a fail-safe system. Usually, a fail-safe system defines a set of safe states. When a fail-safe system can no longer operate according to its specification due to faults, it can transit to one of the predefined safe states when it fails. For example, the computer system that is used to control a nuclear power plant must be a fail-safe system.

Perhaps counter intuitively, it is often des...