- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

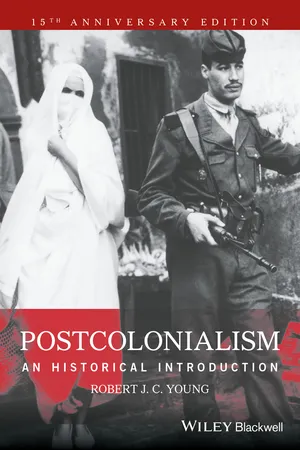

This seminal work—now available in a 15th anniversary edition with a new preface—is a thorough introduction to the historical and theoretical origins of postcolonial theory.

- Provides a clearly written and wide-ranging account of postcolonialism, empire, imperialism, and colonialism, written by one of the leading scholars on the topic

- Details the history of anti-colonial movements and their leaders around the world, from Europe and Latin America to Africa and Asia

- Analyzes the ways in which freedom struggles contributed to postcolonial discourse by producing fundamental ideas about the relationship between non-western and western societies and cultures

- Offers an engaging yet accessible style that will appeal to scholars as well as introductory students

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Postcolonialism by Robert J. C. Young in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Colonialism and the Politics of Postcolonial Critique

In May 2000, Survival, a worldwide organization supporting the rights of tribal peoples, marked the 500th anniversary of the arrival of the first Europeans in Brazil by launching a campaign for land ownership for Brazilian Indians. Entitled ‘Brazil: 500 years of resistance’, Survival’s publicity leaflets highlighted a tristes tropiques history of exploitation and genocide:

When the Portuguese set foot in Brazil, there were five million indigenous peoples. As the invaders introduced disease, slavery and violence, indigenous peoples were virtually wiped out. Today they number 330,000.Indigenous peoples in Brazil still face eviction from their land, violence, and disease at the hands of loggers, settlers, goldminers and powerful politicians and business.

The contemporary gold rush in the Amazon has repeated the conditions of the rubber boom that occurred there at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1910, Sir Roger Casement, a former member of the British Consular Service, was asked by the British government to investigate allegations of atrocities committed against the Putumayo Indians by the Peruvian Amazon Company, a British company engaged in the extraction of rubber on the Brazil–Peru border. Casement was an Irishman who, with E. D. Morel, had earlier been instrumental in exposing the atrocities carried out in the so‐called Congo Free State about which Conrad had written in Heart of Darkness (1899). Michael Taussig has argued convincingly that Casement can be linked to Kurtz in that novel (Taussig 1986). While in Africa, Casement became sceptical towards the idea of the civilizing claims of imperialism, a scepticism that was only increased by what he found in the Amazon basin.

Treatment of the tribal peopleThese are not only murdered, flogged, chained up like wild beasts, hunted far and wide and their dwellings burnt, their wives raped, their children dragged away to slavery and outrage, but are shamelessly swindled into the bargain. These are strong words, but not adequately strong. The condition of things is the most disgraceful, the most lawless, the most inhuman, I believe that exists in the world today. It far exceeds in depravity and demoralization the Congo regime at its worst.… The slavery under which they suffer is an abominable, an atrocious one…. It is appalling to think of all the suffering so‐called Spanish and Portuguese civilization has wantonly inflicted on these people.(Casement 1997: 294–5)

On his return, he submitted a report verifying the atrocities to the British government. In a fine historical irony, Casement, the urbane colonized subject, found himself at the centre of a campaign for the human rights of ‘free’ postcolonial indigenous Brazilians. That historical irony was to be reinforced six years later when the same British government which had knighted him and persuaded him to go to Brazil on its behalf, executed Casement on a charge of High Treason on 3 August 1916. He had been arrested on Banna Strand in County Kerry, on his return to Ireland from Berlin in a German U‐boat, hours before the Dublin Easter Rising. It is not only Latin America, therefore, that has operated within the disjunctive time‐lags of colonial and postcolonial modernity. Nor, as this story shows, was there necessarily any political disjunction between anti‐ and postcolonialism. Whereas postcolonialism has become associated with diaspora, transnational migration and internationalism, anti‐colonialism is often identified exclusively, too exclusively, with a provincial nationalism. From the Boer War onwards, however, it rather took the form of a national internationalism. Like postcolonialism, anti‐colonialism was a diasporic production, a revolutionary mixture of the indigenous and the cosmopolitan, a complex constellation of situated local knowledges combined with radical, universal political principles, constructed and facilitated through international networks of party cells and organizations, and widespread political contacts between different revolutionary organizations that generated common practical information and material support as well as spreading radical political and intellectual ideas. This decentred anti‐colonial network, not just a Black Atlantic but a revolutionary Black, Asian and Hispanic globalization, with its own dynamic counter‐modernity, was constructed in order to fight global imperialism, demonstrating in the process for our own times that ‘globalization’ does not necessarily involve irresistible totalization.

By the time of the First World War, imperial powers occupied, or by various means controlled, nine‐tenths of the surface territory of the globe; Britain governed one‐fifth of the area of the world and a quarter of its population. ‘For the first time’, Lenin noted in 1916, ‘the world is completely divided up, so that in the future only redivision is possible’ (Lenin 1968: 223). With no space left for territorial expansion, the unsatiated empires turned inwards and attempted to devour each other. After the Great War, the two contiguous empires of Austria‐Hungary and Turkey were broken up, and Germany was deprived of its overseas colonies. Germany subsequently tried to turn Europe itself into its colonial empire in an enormous act of migrationist colonialism reworked into the ideology of Lebensraum: it was the great Martiniquan writer, activist and statesman Aimé Césaire who first pointed out in 1950 that fascism was a form of colonialism brought home to Europe (Césaire 1972; W. D. Smith 1986). For the colonial powers the cost of liberation or victory over Germany was the gradual dismemberment of their colonial empires, while defeated Italy lost all its pre‐war colonies in 1945. Japan, which had fought a war of imperialist rivalry with the European colonial powers and, particularly, the United States over Southeast Asia and the Pacific, was deprived of its overseas territorial possessions.

Aside from the colonies of the fascist regimes of Spain and Portugal (which had remained technically neutral during the war), the increasingly fascist apartheid regime of South Africa, and the expanded empires of the Soviet Union and the United States, decolonization by the seven remaining colonial powers of 1945 (Britain, France, Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Australia and New Zealand) occurred relatively quickly. Indian independence in 1947 began a process of European decolonization that is now largely complete, even if the list of colonies, dependent, trust and unincorporated territories, overseas departments, and other such names signifying colonial status in some form is still surprisingly long (still‐extant colonies that enjoy a wide diversity of labels designating their subordinate status as dependent territories include British Gibraltar, the Falklands/Malvinas and a dozen other islands; Danish Greenland; Dutch Antilles; French Guiana, Martinique, Réunion, St Pierre and Miquelon, off Newfoundland; US Puerto Rico, Samoa, Virgin Islands; Spanish Ceuta, Melilla and the Canary Islands). Many of the islands of the Pacific remain colonies of France and the US. Although the United States, as a former colony, can according to Ashcroft, Griffiths and Tiffin (1989) claim technically to be ‘postcolonial’, it soon went on to become a colonial power itself. The USA, the world’s last significant remaining colonial power, continues to control territories that, without reference to the wishes of their indigenous inhabitants, were annexed (Hawaii in 1898, indeed the entire USA from the point of view of native Americans), taken during wars (California, Texas, Nevada, Utah, most of Arizona and New Mexico, part of Colorado and Wyoming, Puerto Rico, Guam), or that were bought from other imperial powers, transactions which, on the analogy of the argument that the Elgin Marbles should be returned to Greece because they were bought by Lord Elgin while Greece was under foreign domination, can no longer be regarded as legitimate (the Louisiana purchase from France in 1803 ($15 million), the purchase of Florida from Spain in 1819, Alaska from the Russian Imperial government in 1867 for $7.2 million; in 1916, in what Tovalou Houénou described as a modern form of the slave trade, the Virgin Islands and their inhabitants were bought from Denmark for $25 million).

The postcolonial era now involves comparable, but somewhat different kinds of anti‐colonial struggles in those countries more recently occupied: East Timor, invaded by Indonesia when a Portuguese colony, now finally independent after a long war of resistance; Tibet by China, Taiwan by nationalist Chinese, Kashmir by India (since the initial dispute over the territory with Pakistan in 1947 was referred to the United Nations, India has stubbornly refused to carry out a UN recommendation to hold a plebiscite of Kashmir’s largely Muslim population to determine whether Kashmir should become independent, or part of India or Pakistan; it continues to occupy the country by military force in the face of fierce local resistance); the Sarhaoui Democratic Arab Republic (Western Sahara) by Morocco, Palestine and the West Bank by Israel – and, as Rodinson (1973) argues, the state of Israel itself; those First Nations seeking independence from sovereign nation‐states (in Canada, Ethiopia, New Zealand, USA) or by indigenous peoples in border territories seeking independence (the Kurds, the Tamils, the Uyghur), or those suffering from the decisions of decolonization who seek union with an adjacent decolonized state (the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland who wish to join a united Ireland), or those tribal peoples who seek nothing more than their own survival, or those who were forcibly transported under colonial occupation, many of whom wish to but cannot return to their own country (the Koreans in Japan), or those fourth‐world nations who seek the basic rights of legal and social equality (native Americans, the Aboriginal peoples of Australia, the so‐called denotified tribes in India, the hill tribes in Bangladesh, the Ainu in Japan), or those suffering from the social stigma of caste exclusion (the Dalits in India, the Burakumin in Japan), or disadvantaged ethnic minorities and impoverished classes in most countries of the world.

These struggles go on side by side while both Europe and the decolonized countries still try to come to terms with the long, violent history of colonialism, which symbolically began over five hundred years ago, in 1492: a history which includes histories of slavery, of untold, unnumbered deaths from oppression or neglect, of the enforced migration and diaspora of millions of peoples – Africans, Americans, Arabs, Asians and Europeans, of the appropriation of territories and of land, of the institutionalization of racism, of the destruction of cultures and the superimposition of other cultures (Chaliand and Rageau 1995; Ferro 1997). Postcolonial cultural critique involves the reconsideration of this history, particularly from the perspectives of those who suffered its effects, together with the defining of its contemporary social and cultural impact. This is why postcolonial theory always intermingles the past with the present, why it is directed towards the active transformations of the present out of the clutches of the past (Sardar, Nandy, Wyn Davies 1993). The postcolonial does not privilege the colonial. It is concerned with colonial history only to the extent that that history has determined the configurations and power structures of the present, to the extent that much of the world still lives in the violent disruptions of its wake, and to the extent that the anti‐colonial liberation movements remain the source and inspiration of its politics. If colonial history, particularly in the nineteenth century, was the history of the imperial appropriation of the world, the history of the twentieth century has witnessed the peoples of the world taking power and control back for themselves. Postcolonial theory is itself a product of that dialectical process.

As a political discourse, the position from which it is enunciated (wherever literally spoken, or published) is located on the three continents of the South, that is, the ‘Third World’. The disadvantages of the term ‘Third World’ have been well rehearsed. It has been subject to sustained criticism, either because identification with it has been perceived as anti‐Marxist (Marxist states made up the ‘Second World’), or because the notion of ‘third’ came to carry a negative aura in a hierarchical relation to the first and second, and gradually became associated with poverty, debt, famine and conflict (Hadjor 1993: 3–11). In this book, therefore, the term ‘Third World’ will be generally avoided, and the geographical, locational and cultural description of the ‘three continents’ and the ‘tricontinental’ (i.e. Latin America, Africa and Asia), endorsed by the Egyptian‐French political scientist Anouar Abdel–Malek after the first conference of the Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America at Havana in 1966, will be used instead (Abdel–Malek 1981, 2: 21; Gerassi 1971, 2: 745–60). It avoids the problems of the ‘Third World’, the bland homogenization of ‘the South’, and the negative definition of ‘the non‐west’ which also implies a complete dichotomy between the west and the rest which two or more centuries of imperialism have hardly allowed. Above all, the tricontinental marks an identification with the great Havana Tricontinental of 1966, which initiated the first global alliance of the peoples of the three continents against imperialism, and the founding moment of postcolonial theory in its journal, the Tricontinental. The problems associated with the term ‘postcolonial’ will be discussed in chapter 5. Suffice it to say at this point that postcolonialism might well be better named ‘tricontinentalism’, a term which exactly captures its internationalist political identifications, as well as the source of its epistemologies.

Postcolonial – or tricontinental – critique is united by a common political and moral consensus towards the history and legacy of western colonialism. It presupposes that the history of European expansion and the occupation of most of the global land‐mass between 1492 and 1945, mark a process that was both specific and problematic. The claim of this history is that there was something particular about colonialism: it was not just any old oppression, any old form of injustice, or any old series of wars and territorial occupations. Modernity theorists such as Ernst Gellner have objected that colonialism does not really merit particular attention in itself, in that its forms of oppression were really no different from those of any other conquest or assertion of power in the past, or indeed from those practised within either traditional and modern societies. Gellner argues that ‘the recent domination of the world by the west can be seen … as primarily an aspect of the transformation of the world by a new technology, economy, and science which happens, owing to the uneven nature of its diffusion, to engender a temporary and unstable imbalance of power’ (Gellner 1993: 3). On this reading colonialism was merely the unfortunate accident of modernity, its only problem resulting from the fact that the west mistook technological advance and the power that it brought for cultural superiority. To sweep colonialism under the carpet of modernity, however, is too convenient a deflection. To begin with, its history was extraordinary in its global dimension, not only in relation to the comprehensiveness of colonization by the time of the high imperial period in the late nineteenth century, but also because the effect of the globalization of western imperial power was to fuse many societies with different historical traditions into a history which, apart from the period of centrally controlled command economies, obliged them to follow the same general economic path. The entire world now operates within the economic system primarily developed and controlled by the west, and it is the continued dominance of the west, in terms of political, economic, military and cultural power, that gives this history a continuing significance. Political liberation did not bring economic liberation – and without economic liberation, there can be no political liberation.

Whereas western expansion was carried out with the moral justification that it was of benefit for all those nations brought under its sway, the values of that spreading of the light of civilization have now been effectively contested. This process has been going on for much of the twentieth century, particularly since the two world wars, the effect of which was not only to show that the imperial powers were militarily vulnerable, particularly to the non‐western power of imperial Japan, but also to cause them to lose the hitherto unquestioned moral superiority of the values of western civilization, in the name of which much colonization had been justified. The west was relativized: the decline of the west as an ideology was irretrievable. Colonialism may have brought some benefits of modernity, as its apologists continue to argue, but it also caused extraordinary suffering in human terms, and was singularly destructive with regard to the indigenous cultures with which it came into contact. For its part, postcolonial critique can hardly claim to be the first to question the ethics of colonialism: indeed, anti‐colonialism is as old as colonialism itself. What makes it distinctive is the comprehensiveness of its research into the continuing cultural and political ramifications of colonialism in both colonizing and colonized societies. This reveals that the values of colonialism seeped much more widely into the general culture, including academic culture, than had ever been assumed. That archeological retrieval and revaluation is central to much activity in the postcolonial field. Postcolonial theory involves a political analysis of the cultural history of colonialism, and investigates its contemporary effects in western and tricontinental cultures, making connections between that past and the politics of the present.

The assumption of postcolonial studies is that many of the wrongs, if not crimes, against humanity are a product of the economic dominance of the north over the south. In this way, the historical role of Marxism in the history of anti‐colonial resistance remains paramount as the fundamental framework of postcolonial thinking. Postcolonial theory operates within the historical legacy of Marxist critique on which it continues to draw but which it simultaneously transforms according to the precedent of the greatest tricontinental anti‐colonial intellectual politicians. For much of the twentieth century, it was Marxism alone which emphasized the effects of the imperialist system and the dominating power structure involved, and in sketching out blueprints for a future free from domination and exploitation most twentieth‐century anti‐colonial writing was inspired by the possibilities of socialism. The contribution of tricontinental theorists was to mediate the translatability of Marxist revolutionary theory with the untranslatable features of specific non‐European historical and cultural contexts. Marxism, which represents both a form of revolutionary politics and one of the richest and most complex theoretical and philosophical movements in human history, has always been in some sense anti‐western, since it was developed by Marx as a critique of western social and economic practices and the values which they embodied. The Bolsheviks themselves always identified their revolution as ‘Eastern’.

If the bulk of anti‐colonialist activism and activist writing in the twentieth century has operated from a Marxist perspective, for the most part it is a Marxism which has been aware of the significance of subjective conditions for the creation of a revolutionary situation, and therefore a Marxism which has been pragmatically modi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface to the Anniversary Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Colonialism and the Politics of Postcolonial Critique

- Part I: Concepts in History

- Part II: European Anti‐colonialism

- Part III: The Internationals

- Part IV: Theoretical Practices of the Freedom Struggles

- Part V: Formations of Postcolonial Theory

- Epilogue: Tricontinentalism, for a Transnational Social Justice

- Letter in Response from Jacques Derrida

- Bibliography

- Index

- End User License Agreement