![]()

Part 1

FUNDAMENTAL AND GENERAL ASPECTS

![]()

Chapter 1

Wetting of Solid Walls and Spontaneous Capillary Flow

Jean Berthier1,* and Kenneth A. Brakke2

1CEA-LETI, CEA/University Grenoble-Alpes, Department of Technology for Life Sciences and Health Care, Grenoble, France

2Department of Mathematics, Susquehanna University, Selinsgrove, PA, USA

Abstract

Spontaneous capillary flows are of great importance in space and biophysics. In space, the gravitational forces are negligible and capillary forces govern liquid motion. In modern biotechnology, the scale of fluidic systems is so small that gravity can be neglected in comparison to capillary forces. In this chapter, we first derive the condition for onset of spontaneous capillary flow in open or confined microchannels; then we present an analysis of the dynamics of the capillary flow that generalizes the Lucas-Washburn-Rideal law to channels of arbitrary section. Finally, we illustrate the theoretical approach by considering the case of suspended capillary microflows.

Keywords: Spontaneous capillary flow (SCF), Gibbs free energy, Lucas-Washburn-Rideal (LWR) law, suspended microflows

1.1 Introduction: Capillary Flows and Contact Angles

At the macroscale, capillary forces seldom have a noticeable effect on physical phenomena. The reason is that their magnitude is much smaller than that of the usual macroscopic forces, such as gravity. However, in two cases capillary forces may become important: in space where gravity is negligible, and at the micro and nano-scale. In this chapter, we focus on the role and effect of capillarity at the microscale for microflows. More specifically, the relation between the wetting of the walls and the capillary flow is investigated, first from a static or quasi-static point of view, and then from a dynamic point of view.

Biotechnology, biology and medicine are domains where capillarity is now widely used. Let us recall that in all these domains, the concepts of point-of-care (POC) and home care are of increasing interest [1-5]. These systems allow for self-testing and telemedicine. Three main types of tests are targeted: first, the search for metabolites—such as cholesterol, glucose, and thyroid hormones; second, the search for viral load—such as viruses and bacteria; and third, blood monitoring—such as the measure of INR (international normalized ratio), coagulation time, prothrombin (PR) time, or blood cell counts. Monitoring at home or at the doctor’s office is an important improvement for the patient: frequent testing, immediate response, no visit to the hospital, and monitoring by telemedicine or directly by the doctor. Such systems must be low-cost, easily portable, sensitive, and robust.

In these domains where biological and chemical targets are transported by liquids, capillary actuation of liquids does not require bulky pumps or syringes, or any auxiliary energy sources. The energy source for the flow is the surface energy of the microchannel walls. On the other hand, conventional forced flow laboratory systems require the help of bulky equipment, which is expensive and not portable.

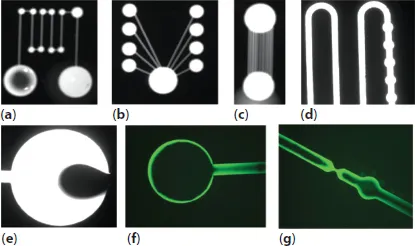

By definition, a spontaneous capillary flow (SCF) occurs when a liquid volume is moved spontaneously by the effect of capillary forces—without the help of auxiliary devices such as pumps or syringes. Capillary systems can be either confined or open, i.e. the liquid moves inside a closed channel or in a channel partially open to the air. On the other hand, composite channels—sometimes partly open or with apertures—are increasingly used, and spontaneous capillary flow is a convenient method to move liquids in such geometries. Some examples of SCF are shown in Figure 1.1.

In this chapter, we first investigate the conditions for spontaneous capillary flow in open or confined microchannels, composite or not, and we show that a generalized Cassie angle governs the onset of SCF [6]. Then we present the dynamics of the capillary flow with a generalized Lucas-Washburn-Rideal expression for the flow velocity and travel distance [7-9]. Finally, we focus on the particular effect of precursor capillary filaments—sometimes called Concus-Finn filaments [10,11]—that sometimes exist in sharp corners, depending on the wettability of the walls.

1.2 A General Condition for Spontaneous Capillary Flow (SCF)

In this section, we analyze the conditions for the onset of SCF, i.e. the equilibrium state that is the limit for a capillary flow. Any change in these conditions results either in an advancing SCF, or in the receding of the liquid in the channel. We shall see that SCF depends on the wetting angle of the liquid with the walls, and on the geometry of the channel. Geometry has a profound influence on the channel’s ability to allow for a capillary flow. Geometries facilitating the establishment of capillary flows in confined or open channels have been experimentally and numerically investigated [12-20].

From a theoretical standpoint, a first approach valid for confined or open channels with a single wall contact angle (uniform surface energy) has been recently proposed [21]. Later a general condition for SCF in confined or open microchannels, composite or not, was established based on the Gibbs free energy expression [6,22]. It is this latter condition—the most general—that we present next.

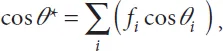

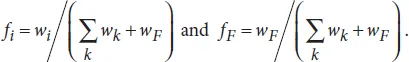

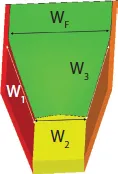

Let us consider the general case of a channel of uniform cross section, with a boundary with the surrounding air, and composite walls of different nature as sketched in Figure 1.2. We show that the condition for SCF onset is simply that the generalized Cassie angle for the composite surface be smaller than 90°. Let us recall that the generalized Cassie angle θ* is the average contact angle defined in the appropriate way, i.e.

where the θi are the Young contact angles with each component i, and the fi are the areal fraction of each component i in a cross section of the flow (Figure 1.2). The free interface with air is denoted by the index F.

1.2.1 Theoretical Condition

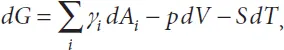

Our starting point is the Gibbs thermodynamic equation [22]

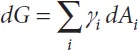

where G is the Gibbs free energy, Ai the liquid contact areas with the different boundary materials, γi the liquid interface tensions with the different boundary materials, V the liquid volume, p the liquid pressure, S the entropy and T the temperature. Generally in biotechnology (except for the very special cases where heating is used, such as for polymerase chain reaction PCR), the temperature is kept constant and the last term of (1.2) vanishes. Assuming a constant temperature, we consider the two following cases: first, the liquid volume is constant, as for a drop with negligible or slow evaporation, and second, an increasing volume of liquid. In the first case, (1.2) reduces to

The equilibrium position of the droplet is obtained by finding the minimum of the Gibbs free energy. In this case, the minimization of the Gibbs free energy is equivalent to the minimization of the liquid surface area.

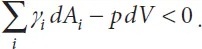

The second case—that of an SCF—is different: the volume of liquid is not constant in the system (dV ≠ 0), and the system evolves in the direction of lower energy. Hence

The morphology of the free surface is such that it evolves to reduce the Gibbs free energy G. For simplicity, we first consider a uniform channel with a single contact angle and open to the air. The liquid (L) then has contact with solid (S) and air (G) as sketched in Figure 1.3.