- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Recognized as a finalist for the CAE 2018 Outstanding Book Award!

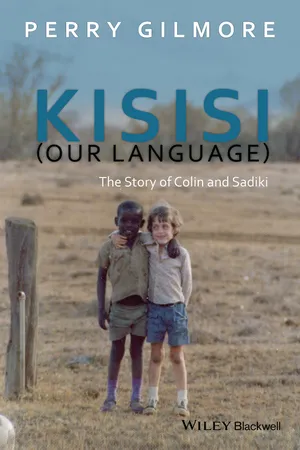

Part historic ethnography, part linguistic case study and part a mother's memoir, Kisisi tells the story of two boys (Colin and Sadiki) who, together invented their own language, and of the friendship they shared in postcolonial Kenya.

Part historic ethnography, part linguistic case study and part a mother's memoir, Kisisi tells the story of two boys (Colin and Sadiki) who, together invented their own language, and of the friendship they shared in postcolonial Kenya.

- Documents and examines the invention of a 'new' language between two boys in postcolonial Kenya

- Offers a unique insight into child language development and use

- Presents a mixed genre narrative and multidisciplinary discussion that describes the children's border-crossing friendship and their unique and innovative private language

- Beautifully written by one of the foremost scholars in child development, language acquisition and education, the book provides a seamless blending of the personal and the ethnographic

- The story of Colin and Sadiki raises profound questions and has direct implications for many fields of study including child language acquisition and socialization, education, anthropology, and the anthropology of childhood

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Kisisi (Our Language) by Perry Gilmore in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Antropología cultural y social. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

UWERYUMACHINI!: A LANGUAGE DISCOVERED

The limits of language are reached when language becomes unfamiliar, alien, altered. The limits mark a boundary between the known and the unknown, between the self and the other … The confrontation with the unknown in language inevitably produces a reassessment of the known. Stories of the encounter with the other have written into them stories of the discovery, and rediscovery, of the self.Martin Calder1

“serendipity” … the discovery, by chance or sagacity, of valid results which were not sought for … the observation is anomalous, surprising, either because it seems inconsistent with prevailing theory or with other established facts. In either case, the seeming inconsistency provokes curiosity; it stimulates the investigator to “make sense of the datum,” to fit it into a broader framework of knowledge.Robert Merton2

“Uweryumachini!!” Colin and Sadiki kicked up puffs of hot pale dust as they jumped up and down, excitedly yelling and pointing to a small airplane flying high above them in the clear blue Kenya sky. “Uweryumachini!” They gleefully giggled and shouted. With outstretched arms they reached up, jumping high, as if to touch the winged visitor. Then turning to each other, face to face, with their mouths and eyes wide open in exaggerated expressions of surprise, they burst into wild laughter again. Huge smiles flashed across their faces as they loudly chanted over and over, “Uweryumachini!!” Eyes glistening with delight, they continued their ecstatic shouting and jumping with eager rhythmic repetition. It was as if the greatest discovery had just interrupted their daily morning soccer ball ritual. The unexpected airborne surprise buzzed its way across the vast sky that reflected itself perfectly in the flamingo-rimmed glassy blue soda lake below. It buzzed high over the endless savannah landscape marked by dramatic volcanic craters and the sharply carved lines of precipitous steep scarps and rocky cliffs that were so characteristic of this part of the Great Rift Valley. The massive sky and uninterrupted sweeping panoramic view surrounded the two little boys in all directions. “Uweryumachini!! Uweryumachini!!” Their voices rang out on the remote hillside wrapped in playful giggles as they shared their sheer, intense, and playful joy!

It was 1975. Colin's father and I were both graduate students studying the communicative behaviors of a troop of 92 wild olive baboons (Papio anubis). Hugh Gilmore, my husband then, was a doctoral student in physical anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, conducting his dissertation research on adult male face-to-face social interaction with a focus on their communicative vocalizations. I was completing research for my Master's degree in education, focused on developmental psychology at Temple University, examining how juvenile baboons learned, interpreted, and displayed their place in, and knowledge of, the troop's complex hierarchical ranking system.3 We were observing a free-ranging baboon troop that previous researchers had named the Pumphouse Gang, after the Tom Wolfe book.4 The aptly named baboon troop often “hung out” near a small pump house, a pumping station for the ranch's water supply system that was at the bottom of a cliff in the center of their home range. The Pumphouse Gang was one of many troops that lived and foraged on Kekopey Ranch, a sprawling 48,000 acre cattle farm near the town of Gilgil, Kenya. Arthur and Tobina Cole, the ranch's aristocratic British colonial second-generation Kenya land owners, had generously made an old uninhabited manager's house available as a headquarters for the Gilgil Baboon Research Project.

For the five years before we arrived, the headquarters had been home to a string of primatologists, mostly students of the American physical anthropologist Sherwood Washburn, a pioneer in the field of primatology. The house was situated on an isolated hillside on a high bluff at the far south end of the huge ranch, eight miles from the Coles' antique-filled historic farmhouse. The baboon headquarters was an airy six-room tin-roofed stone bungalow with the exterior painted a deep earth-colored red. The Red House (Kiserigwa), as it was often called, would be our family's new home for the next 15 months.

The researchers at the Gilgil Baboon Research Project shared the hillside with a half dozen African ranch workers and their families. The African workers' way of life stood in striking contrast to both the aristocratic entitled lifestyle of the British colonial land owners and to the privileged position of the Gilgil Baboon Project's researchers. The hillside African residents worked either for the ranch or for the project earning very meager wages. The Gilgil Baboon Project workers were better paid, earning increasing amounts over the years, from $40 a month in the early years, up to $100 in the later years. They lived with their families in two very small one-room stone dwellings just over the rise, about 50 yards away, on the other side of the hill. Sadiki was the son of a Samburu mother and Turkana father. Sadiki's parents were ranch workers for the Coles. Sadiki and his four sisters lived in one of the stone dwellings on the hillside with their parents, who herded cattle on foot and ran the pumps for the cattle's water supply, fed from a hot spring on the far north side of the ranch.

The cluster of African families on the hillside was multilingual, representing four to six tribal peoples. Each family spoke its own tribal language to each other. There was a broad range of diverse linguistic repertoires including Abaluhya, also known as Luhya, a Bantu language, and Luo, Maasai, Turkana, and Samburu (i.e., North Maa), all Nilotic languages with Luo being more distantly related to the others. There was occasional use of Kipsigis, Boran, and Somali depending on the presence of rotating ranch employees living on the hill. Our family spoke English as had all the previous researchers in the Red House. The language used to communicate across these highly marked and compartmentalized linguistic and cultural borders was a regional variety of Kiswahili, often called Up-Country Swahili, Kitchen Swahili, Kisetta, or Kisettla.5 The local variety of Swahili spoken in this region of the Kenya bush is not to be confused with Standard or East Coast Kiswahili.6 This Up-Country variety, a simplified or pidginized Swahili that Hancock has referred to as the “most aberrant variety”7 of Swahili, was a second language for African people living in Up-Country Kenya. It was also historically the language the colonial employers used to communicate with their African servants and workers.

The first day we arrived at the headquarters, all of the hillside residents were lined up in the small open courtyard standing in a row ready to formally greet the new wazungu (white) researchers. They had heard us approaching long before we turned our white Kombi Volkswagen bus on to the long dirt track that led up the hill to the Red House. Mike and Cordelia Rose, colleagues who were studying colobus monkeys at nearby Lake Naivasha, had kindly hosted us in their small whitewashed mud and wattle thatched roof cottage the night before. The distinctive bellows, snorts, and grunts of nearby hippos and myriad other strange new animal sounds filled the cool night air as our little family tried to fall asleep anticipating the new life awaiting us, just miles away.

In the morning Mike and Cordelia led us, caravan style, to the headquarters where they had often visited the previous baboon researchers. Our two vehicles stirred up long trailing veils of tawny dust clouds as we made our way across the parched and sun-baked savannah and up the hill, stopping to carefully open and close the cattle paddock gates before arriving at the headquarters. We all climbed out of the vehicles and began to exchange jambo's (hello's), smiles and introductions, each of us shaking hands as we walked down the warm and welcoming reception line.

Colin and Sadiki's eyes fixed on each other almost immediately. Sadiki stood out among his older and younger sisters. The boys were just about the same height and age. We would discover later that their birthdays were only one month apart. In the midst of the initial awkward formality and confusion around our introductions, everyone easily observed the instant magnetism between the two boys. Their new friendship took only a few days to emerge. From the fourth day after we arrived at the research station, Sadiki and Colin spent most of their days together, sunrise to sunset. They were to become inseparable friends, playing together almost daily for the next 15 months.

Initially the two children struggled to communicate in the local Up-Country Swahili, visibly using lots of gestures and charades during the first days and weeks. A soccer ball, a wheel rim and a stick, an old rope swing hanging from the lone tree in the courtyard, and the collection of match box cars Colin brought with him were favorite and frequent play props. Lying side by side on Colin's bed, looking at Tintin comic books, they softly pointed out pictures of simba (lion), samaki (fish), and the few Swahili words they seemed to know in common. It was heartwarming to observe them together. A little more than a month after our arrival, I wrote in my journal, “Sitting on the little wooden kitchen chairs in the cool courtyard shade, Sadiki patiently teaches Colin a melodious traditional Samburu song. Sadiki's rich peaceful voice sounds so wise and old for just a little boy as he softly chants the haunting Samburu melody; trance-like, tranquil, and knowing. Colin hums along catching a few syllables and soon his little voice is singing along and sounding surprisingly deep and wise and peaceful too.” Within just a few months they seemed to be in effortless and continual conversation as they pretended to hunt herds of Thomson gazelles in the tall grasses or raced match box cars in an imaginary African safari rally game, each playing “Action Man” or “Batman.”

I was treasuring their budding friendship and so pleased to see Colin learning Swahili in such a playful loving way. He had not really been all that enthusiastic about the more formal vocabulary instruction I had been offering. In those early weeks I hadn't yet realized that Sadiki's first and primary language in the home was actually Samburu and that he was not a fluent Swahili speaker.

“Uweryumachini! Uweryumachini!” The two boys called out again and again as they continued jumping up and down, pointing to the sky and gleefully shouting at the small airplane flying high above them. Their giggles punctuated each utterance. Their voices carried over the swirl of late morning breezes and through the open window where I was working at my desk. I looked up to see them completely engaged in their exuberant play. I smiled, seeing them enjoying themselves so thoroughly, feeling so glad we had come to Kenya.

“Uweryumachini!” they shouted out again. I strained to listen to what they were saying, their high-pitched laughing voices somewhat muffled by the steady constant breeze so familiar on this high bluff above the basin of the Great Rift Valley. I was certain the local Swahili word for “airplane” was “ndege” but I couldn't quite hear what the boys were calling out. Leafing through my Swahili dictionary, I could find nothing even close to what I thought I heard them shouting. I wasn't sure how to spell or even parse it. Was it a single word? A phrase? I leaned across my desk and called to the boys to come closer to the open window. They approached and I asked them what they were saying. They mumbled something but I still couldn't understand. I urged them to repeat themselves slowly so that I could hear them more clearly. They paused and looked at each other as if a great secret had just been revealed – and not quite sure if they had gotten themselves in trouble. They giggled again, then slowly and hesitantly, with furtive sideways glances at each other, pronounced something that sounded to me like “who-are-you-machini”! They uttered the phrase as a single word with a Swahili “accent.” I would eventually discover that their “word” for airplane was part of a continuously expanding vocabulary and grammar that made their speech, a language variety I was to ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series

- Titlepage

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Map

- Prologue

- Chapter 1: Uweryumachini!: A Language Discovered

- Chapter 2: Herodotus Revisited: Language Origins, Forbidden Experiments, New Languages, and Pidgins

- Chapter 3: Lorca's Miracle: Play, Performance, Verbal Art, and Creativity

- Chapter 4: Kekopey Life: Transcending Linguistic Hegemonic Borders and Racialized Postcolonial Spaces

- Chapter 5: Kisisi: Language Form, Development, and Change

- Epilogue

- In Memoriam

- References

- Index

- Plates

- EULA