![]()

Chapter 1

The Multiple Roles of Various Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Photosynthetic Organisms1

Franz-Josef Schmitt1, Vladimir D. Kreslavski2,3, Sergey K. Zharmukhamedov3, Thomas Friedrich1, Gernot Renger1, Dmitry A. Los2, Vladimir V. Kuznetsov2, Suleyman I. Allakhverdiev2,3,4,5,*

1Technical University Berlin, Institute of Chemistry, Max-Volmer-Laboratory of Biophysical Chemistry, Straße des 17. Juni 135, D-10623 Berlin, Germany

2Institute of Plant Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Botanicheskaya Street 35, Moscow 127276, Russia

3Institute of Basic Biological Problems, Russian Academy of Sciences, Institutskaya Street 2, Pushchino, Moscow Region 142290, Russia

4Department of Plant Physiology, Faculty of Biology, M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, Leninskie Gory 1-12, Moscow 119991, Russia

5Department of New Biology, Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science & Technology (DGIST), 333 Techno jungang-daero, Hyeonpung-myeon, Dalseong-gun, Daegu, 711-873, Republic of Korea

Abstract

This chapter provides an overview on recent developments and current knowledge about monitoring, generation and the functional role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) – H2O2, HO2•, HO•, OH− 1,O2 and O2−• – in both oxidative degradation and signal transduction in photosynthetic organisms including a summary of important mechanisms of nonphotochemical quenching in plants. We further describe microscopic techniques for ROS detection and controlled generation. Reaction schemes elucidating formation, decay and signaling of ROS in cyanobacteria as well as from chloroplasts to the nuclear genome in eukaryotes during exposure of oxygen-evolving photosynthetic organisms to oxidative stress are discussed that target the rapidly growing field of regulatory effects of ROS on nuclear gene expression.

Keywords: photosynthesis, plant cells, reactive oxygen species, ROS, oxidative stress, signaling systems, chloroplast, cyanobacteria, nonphotochemical quenching, chromophore-activated laser inactivation, sensors

1.1 Introduction

About 3 billion years ago the atmosphere started to transform from a reducing to an oxidizing environment as evolution developed oxygenic photosynthesis as key mechanism to efficiently generate free energy from solar radiation (Buick, 1992; Des Marais, 2000; Xiong and Bauer, 2002; Renger, 2008; Rutherford et al., 2012; Schmitt et al., 2014a). Entropy generation due to the absorption of solar radiation on the surface of the Earth was retarded by the generation of photosynthesis, and eventually a huge amount of photosynthetic and other organisms with rising complexity developed at the interface of the transformation of low entropic solar radiation to heat. The subsequent release of oxygen as a “waste” product of photosynthetic water cleavage led to the present-day aerobic atmosphere (Kasting and Siefert, 2002; Lane, 2002; Bekker et al., 2004), thus opening the road for a much more efficient exploitation of the Gibbs free energy through the aerobic respiration of heterotrophic organisms (for thermodynamic considerations, see (Nicholls and Ferguson, 2013; Renger, 1983).

From the very first moment this interaction with oxygen generated a new condition for the existing organisms starting an evolutionary adaptation process to this new oxydizing environment. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) became a powerful selector and generated a new hierarchy of life forms from the broad range of genetic mutations represented in the biosphere. We assume that this process accelerated the development of higher, mainly heterotrophic organisms in the sea and especially on the land mass remarkably.

The efficient generation of biomass and the highly selective impact of ROS lead to a broad range of options for complex organisms to be developed in the oxydizing environment. The direct, mostly deleterious impact of ROS on the biosphere is thereby just a minor facet in the broad spectrum of consequences. Important and more complex side effects are for example given by the fact that the molecular oxygen led to generation of the stratospheric ozone layer, which is the indispensable protective shield against deleterious UV-B radiation (Worrest and Caldwell, 1986). ROS led to new complex constraints for evolution that drove the biosphere into new directions – by direct oxidative pressure and by long-range effects due to environmental changes caused by the atmosphere and the biosphere themselves as energy source for all heterotrophic organisms.

For organisms that had developed before the transformation of the atmosphere the pathway of redox chemistry between water and O2 by oxygenic photosynthesis was harmful, due to the deleterious effects of ROS. O2 destroys the sensitive constituents (proteins, lipids) of living matter. As a consequence, the vast majority of these species was driven into extinction, while only a minority could survive by finding anaerobic ecological niches. All organisms developed suitable defense strategies, in particular the cyanobacteria, which were the first photosynthetic cells evolving oxygen (Zamaraev and Parmon, 1980).

The ground state of the most molecules including biological materials (proteins, lipids, carbohydrates) has a closed electron shell with singlet spin configuration. These spin state properties are of paramount importance, because the transition state of the two electron oxidation of a molecule in the singlet state by 3Σ−gO2 is “spin-forbidden” and, therefore, the reaction is very slow. This also accounts for the back reaction from the singlet to the triplet state.

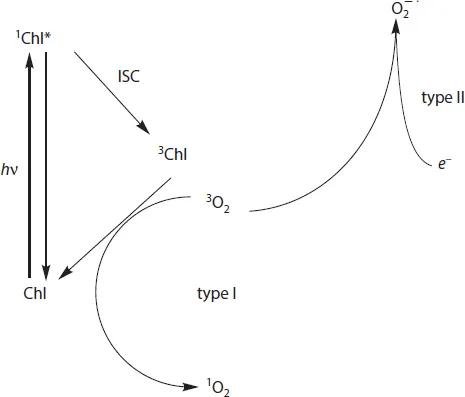

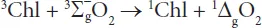

In contrast to this majority of singlet ground state molecules the electronic configuration of the O2 molecule in its ground state is characterized by a triplet spin multiplicity described by the term symbol 3Σ−gO2. This situation drastically changes by two types of reactions which transform 3Σ−gO2 into highly reactive oxygen species (ROS): i) Electronic excitation leads to population of two forms of singlet O2 characterized by the term symbols 1Δg and 1Σ+g. The 1Σ+g state with slightly higher energy rapidly relaxes into 1ΔgO2 so that only the latter species is of physiological relevance (type I). ii) Chemical reduction of 3Σ−gO2 (or 1ΔgO2) by radicals with non-integer spin state (often doublet state) leads to formation of O−•2, which quickly reacts to HO2• and is subsequently transferred to H2O2 and HO• (vide infra) (type II). In plants, the electronic excitation of 3Σ−gO2 occurs due to close contact to chlorophyll triplets that are produced during the photoexcitation cycle (Schmitt et al., 2014a) (see Figure 1.1, Figure 1.2). Singlet oxygen is predominantly formed via the reaction sensitized by interaction between a chlorophyll triplet (3Chl) and ground state triplet 3Σ−gO2:

3Chl can be populated either via intersystem crossing (ISC) of antenna Chls or via radical pair recombination in the reaction centers (RCs) of photosystem II (PS II) (for reviews, see Renger, 2008; Vass and Aro, 2008; Rutherford et al., 2012; Schmitt et al., 2014a). Alternatively, 1ΔgO2 can also be formed in a controlled fashion by chemical reactions, which play an essential role in programmed cell death upon pathogenic infections (e.g. by viruses).

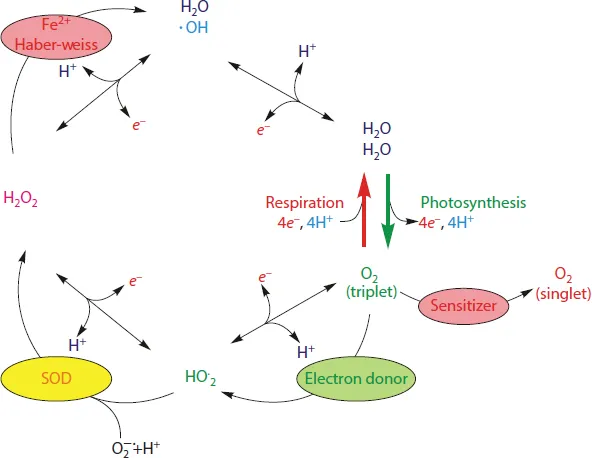

Figure 1.2 schematically illustrates the pattern of one-electron redox steps of oxygen forming the ROS species HO•, H2O2 and HO•2/O−•2 in a four-step reaction sequence with water as the final product. The sequence comprises the water splitting, leading from water to O2 + 4H+ and the corresponding mechanism vice versa of the ROS reaction sequence. The production of 1Δg O2 is a mechanism next to that.

In biological organisms, the four-step reaction sequence of ROS is tamed and energetically tuned at transition metal centers, which are encapsulated in specifically functionalized protein matrices. This mode of catalysis of the “hot water redox chemistry” avoids the formation of ROS. In photosynthesis, the highly endergonic oxidative water splitting (ΔG° = + 237.13 kJ/mol, see Atkins, 2014) is catalyzed by a unique Mn4O5Ca cluster of the water-oxidizing complex (WOC) of photosystem II and energetically driven by the strongly oxidizing cation radical P680+• (Klimov et al., 1978; Rappaport et al., 2002) formed via light-induced charge separation (for review, see Renger, 2012).

Correspondingly, the highly exergonic process in the reverse direction is catalyzed by a binuclear heme iron-copper center of the cytochrome oxidase (COX), and the free energy is transformed into a transmembrane electrochemical potential difference for protons (for a review, see Renger, 2011), which provides the driving force for ATP synthesis (for a review, see Junge, 2008). In spite of the highly controlled reaction sequences in photosynthetic WOC and respiratory COX, the formation of ROS in living cells cannot be completely avoided. The excess of ROS under unfavorable stress conditions causes a shift in the balance of oxidants/antioxidants towards oxidants, which leads to the intracellular oxidative stress (Kreslavski et al., 2012b). Formation of ROS (the production rate) as well as decay of ROS (the decay rate) with the latter one determining the lifetime, both bring about the concentration distribution of the ROS pool (Kreslavski et al., 2013a). The activity of antioxidant enzymes, superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, peroxidases, and several others, as well as the content of low molecular weight antioxidants, such as ascorbic acid, glutathione, tocopherols, carotenoids, anthocyanins, play a key role in regulation of the level of ROS and products of lipid peroxidation (LP) in cells (Apel and Hirt, 2004; Pradedova et al., 2011; Kreslavski et al., 2012b).

The exact mechanisms of neutralization and the distribution of ROS have not been clarified so far. Especially the involvement of organelles, cells and up to the whole organism, summarizing the complicated network of ROS signaling (see chap. 6 and 7) are still far from being completely understood (Swanson and Gilroy, 2010; Kreslavski et al., 2012...