eBook - ePub

Intracorporeal Robotics

From Milliscale to Nanoscale

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A promising long-term evolution of surgery relies on intracorporeal microrobotics. This book reviews the physical and methodological principles, and the scientific challenges to be tackled to design and control such robots. Three orders of magnitude will be considered, justified by the class of problems encountered and solutions implemented to manipulate objects and reach targets within the body: millimetric, sub-millimetric in the 10- 100 micrometer range, then in the 1-10 micrometer range. The most prominent devices and prototypes of the state of the art will be described to illustrate the benefit that can be expected for surgeons and patients. Future developments nanorobotics will also be discussed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Intracorporeal Robotics by Michael Gauthier,Nicolas Andreff,Etienne Dombre in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Tecnología e ingeniería & Robótica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Intracorporeal Millirobotics

1.1. Introduction

Intracorporeal millirobots are at the boundary of conventional surgical robots that are installed in the operating room (OR) along the table or on the patient. They still work in the macroworld, where volumic forces and torques (such as weight) dominate. Under this designation, we mean devices with either partially or fully intracorporeal actuated degrees of freedom (DoFs). Their dimensions in the body can reach at the maximum a few tens of millimeters. The dimensions of the surgical site range from a few millimeters to a few centimeters; however, when it is mobile, the millirobot may cover a workspace of several cubic centimeters. The forces exerted on tissues by the robot range from a few millinewtons to several newtons, up to tens of newtons for retraction of organs or gripping a needle.

At this scale, many prototypes have been developed, even though very few of them have entered the OR. In many cases, they look like conventional robots for which rigid body kinematic models and vision-based or force-based control algorithms may be used. More or less, they could be seen as miniaturized versions of existing solutions.

However, to comply with the environment constraints (biological tissues, safety, etc.) and the task constraints (access to deep anatomical spaces, preservation of vital structures, high dexterity, etc.), many efforts have been made to design original kinematics with advanced sensing capabilities for manipulation and locomotion purposes. A promising approach is now to integrate robotics in instruments rather than to think of the robot as a simple instrument holder.

In section 1.2, we will present a variety of millimetric devices providing intracorporeal manipulation and/or mobility capabilities. In section 1.3, we will address scientific issues that are specific to robotics at milliscale. These issues cover the main fields of robotic research in modeling, design, actuation, sensing and control. In section 1.4, we will present in more detail three robotic systems that are representative of the state of the art at the milliscale: a dual-arm master–slave system, a snake-like robot made up of concentric tubes and a handheld robotized instrument.

1.2. Principles

We present in this section the principles of three classes of devices:

– partially intracorporeal devices with active distal mobilities;

– intracorporeal manipulators;

– intracorporeal mobile devices.

Their purpose is functional exploration (in the case of capsules) as well as intervention (to remove a polyp, place a stent, deliver a drug in a localized manner, etc., but also cut, retract, dissect and cauterize as in conventional surgery). Emphasis has been put on several representative devices of each class to review functional qualities and limits of potential robotic solutions. A more comprehensive review of many prototypes worldwide can be found in [DOM 12b].

1.2.1. Partially intracorporeal devices with active distal mobilities

Under this denomination, we mean conventional instruments that have been modified to improve dexterity and/or precision of the surgeon or the radiologist. We include, for instance, any device providing two additional actuated DoFs between the entry port in the body and the tool (retractor, forceps, needle driver, but also tip of an endoscope), not accounting for the closing/opening of the jaws of the tool if any. The partially intracorporeal device is generally attached to an external device that can be a robot providing supplementary DoFs. It is driven externally by the surgeon, either directly in a comanipulation mode (section 1.3.5.3) or from a master workstation in a teleoperation mode (section 1.3.5.2) (Figure 1.1).

With such a definition, we consider entering into this class the actuated instruments for endoscopic surgery and the catheters. Typically, the diameter of these instruments is restricted to 8–10 mm in abdominal surgery, 5–6 mm in cardiac surgery, even 2.5–3 mm for intrauterine fetal surgery [HAR 05, ZHA 09a], 0.5–2 mm for an active catheter.

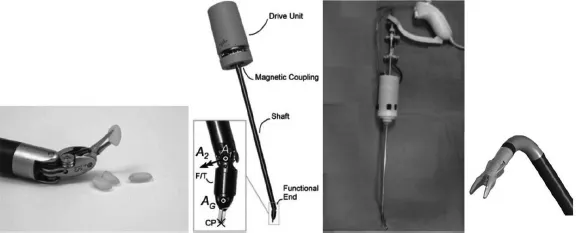

Figure 1.1. Partially intracorporeal DoFs: a) comanipulated instrument; b) teleoperated instrument [SAL 04]

1.2.1.1. Actuated instruments for endoscopic surgery

As opposed to open surgery, endoscopic surgery has revolutionized surgical practice since the early 1970s. Often referred to as minimally invasive surgery (MIS), it reduces postsurgery wounds, the risk of infection, the recovery time and the cost of treatment. But it suffers from a certain number of shortcomings: loss of internal mobility due to kinematic constraints induced by the trocar, hand–eye coordination due to the inversion of directions of motion of the hands and the tool tip, loss of force and tactile feedback, restricted workspace and surgeon’s fatigue. These limitations have motivated the development and introduction of robots in the OR. Since the mid-1990s, with the robotic systems ZEUS (Computer Motion1) and Da Vinci (Intuitive Surgical2), master–slave architecture has been adopted for MIS: the instruments are carried by two or three slave manipulators teleoperated by the surgeon from a remote master console. Along the same lines, it is worth mentioning the platforms Raven II from University of Washington [HAN 13] and MiroSurge from DLR [HAG 10] that are dedicated to research in robotic surgery.

In these systems, the active part of each instrument may have up to two actuated DoFs (not including actuation of the gripper) mounted at the distal end of a rigid hollow tube through which the driving cables pass (Figure 1.2, left). Such additional DoFs may also be mounted at the distal part of a lightweight handheld system (Figure 1.2, right) that gives the surgeon the ability to comanipulate the instrument without using a master arm [ZAH 10]. In both cases, the additional pan and tilt rotations compensate for the loss of mobility induced by the constraint of passage through the trocar.

Figure 1.2. From left to right: close-up of the Da Vinci Endowrist tip manipulating rice grains; DLR MICA instrument of the MIRO platform for endoscopic surgery and close-up of the two-DoF wrist mounted with a force/torque (FT) sensor [HAG 10]; the EndoControl3 handheld laparoscopic instrument JAiMY [ZAH 10]; close-up of the two-DoF bending and rotary wrist of JAiMY

1.2.1.2. Actuated catheters

A catheter is a thin (a few millimeter in diameter), long (of the order of a meter) and hollow tube that allows the passage of functional catheters of smaller diameter. These may hold various miniature sensors (pressure, ultrasound probe, optical fiber, etc.) or instruments, e.g. for the local administration of a drug, the insertion of a prosthesis (stent, angioplasty balloon, etc.), the endovascular coiling of aneurysms, the puncture/biopsy for diagnostic purposes or tumor destruction (radiofrequency abalation, laser therapy, etc.) [CHA 00]. The catheter is inserted into an artery, usually in the groin. It is steered, under radiographic control, by the doctor who rotates it around its longitudinal axis and pushes it to its destination. This is made difficult because of the narrowness of the vessel, the frictions on the wall and the many bifurcations. The difficulty for the surgeon is thus to transmit force and motion to the end effector with little or no relevant kinesthetic feedback, and with a restricted and sparse visual feedback to limit the radiation doses, while avoiding perforation of the artery.

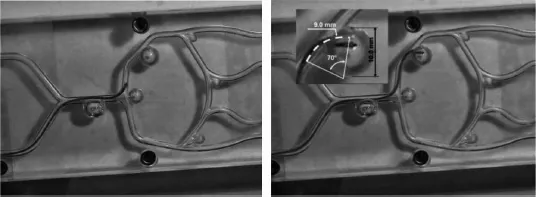

An active catheter is shown in Figure 1.3 [SZE 11]. It is endowed with guidance abilities to facilitate its introduction in bifurcations that exhibit restrictive directions (including very acute closed angles). There are some similarities between an active catheter and a teleoperated robotized colonoscope, however, the diameter is nearly one order of magnitude lower, typically 1–2 mm (the diameter can be reduced to 0.5–1 mm in the case of a guidance catheter). The other difference, and the major difficulty, is that the catheter must move in an artery where the pressure and the blood flow are important. Many prototypes of active catheters have been developed over the last 10 years where many actuation concepts have been explored as will be presented in section 1.3.3.

Figure 1.3. Navigation of an active catheter in a phantom of an aneurysm in the Willis Polygon (Ø = 1.1 mm, radius of curvature = 9 mm) [SZE 11]

To protect the surgeon against radiation, master–slave systems, which allow the doctor to remotely control the catheter, are now available, such as the Sensei X Robotic System, and more recently the Magellan Robotic System, both marketed by Hansen Medical4, or the Amigo RSC from Catheter Robotics5. These systems offer a steering unit that pushes and allows bidirectional rotations of the catheter tip.

1.2.2. Intracorporeal manipulators

We give the name intracorporeal manipulators to any device providing full (or at least more than 2) mobility to the tool with actuated DoFs located between the entry port in the body and the tool. These devices may be minimanipulators (scaled version of conventional robot arms) or flexible instruments designed to perform new techniques of surgery without visible scaring. We also include in this class modular approaches aiming at assembling and disassembling (or possibly deploying and retracting) robots and platforms within the body.

1.2.2.1. Minimanipulators

Typically, minimanipulators have a centimetric size, generating submillimetric to centimetric displacements and can exert forces of the order from 1 N (e.g. to insert a needle into a coronary artery) to several tens of newtons to retract tissue. Different options may be adopted in the design:

– discrete architectures with embedded actuators;

– discrete architectures with remote actuators (outside the patient);

– continuum architectures (or snake-like or elephant trunk like architectures) with remote actuators.

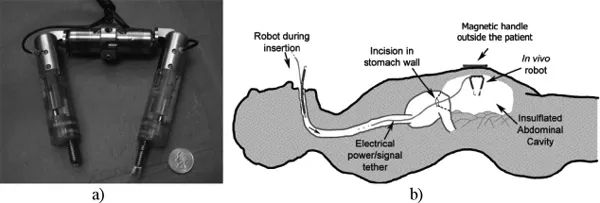

Discrete architectures have a limited number of rigid links and discrete joints. A first example of such robot with embedded actuators, designed for natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) (section 1.2.2.2), is shown in Figure 1.4 [LEH 08, TIW 10]: it consists of two prismatic arms each connected to a central body by a revolute joint, together providing four planar DoFs. Each arm is fitted with either a grasper forceps or a cautery end effector. The central body contains a stereo camera pair and magnets that interact with external magnets to attach the robot to the interior abdominal wall. It is inserted through the esophagus and into the peritoneal cavity using an overtube in a configuration where the arms are disconnected from the central body.

Figure 1.4. a) In vivo two-arm dexterous robot from Vanderbilt University; b) NOTES procedure [LEH 08, TIW 10]

Another example is the modular robot DRIMIS [SAL 04] (Figure 1.5(a)), which is the result of an optimization procedure using multiobjective evolutionary algorithms, coupled with a realistic simulation of the intended surgical task (anastomosis during coronary artery bypass grafting). Several one-DoF and two-DoF modules (Ø 10 mm, 25–40 mm long) were designed with different axis organization. Typically, a six-DoF arm is 120 mm long.

The arms of the dual-arm robot SPRINT have a similar kinematics. The platform was developed in the frame of the EU FP7 Araknes project6 [PIC 10, SAN 11] (Figure 1.5(b)). Each arm has six DoFs plus the gripper. Four additional DoFs are provided by the external positioning device. In its current version, the size is 18 mm in diameter and 120 mm in length. It can exert forces up to 5 N. The robot is intended to be attached to the umbilical access port in single-port access (SPA) surgery (see section 1.2.2.2). A detailed description of the system is presented in section 1.4.1.

Figure 1.5. Architectures with rigid links and discrete joints: a) DRIMIS (ISIR) [SAL 04]; b) SPRINT (Araknes project) [PIC 10, SAN 11]

When miniature actuators are embedded in the structure, one of the difficulties is the routing of the electrical cables, another is the small power-to-weight ratio of the actuators available at this size, dramatically restricting the forces that can be exerted by the robot on tissues. The latter no longer holds with remote actuators. However, remote actuation implies using mechanical wires to drive the joint, which is a more tricky issue than routing electrical cables. An example of such an architecture designed by Ikuta et al. [IKU 03] is depicted in Figure 1.6: the Hyper Finger (Mark-3) is a seven-DoF (including the forceps griping action) wire-driven active forceps for laparoscopic surgery (Ø 10 mm). A special decoupled two-DoF “ring-joint” mechanism was developed, where each DoF can be driven independently. It is teleoperated with an analogous seven-DoF master finger.

An interesting alternative to the discrete aforementioned minimanipulators is the continuum robots. They have a smaller outer diameter with comparable performance specifications [XU 12]. They more or less extend the design used for bending the tip of active catheters. The actuators are placed outside the patient, pulling cables or “tendons” of different technologies to control distributed stiffness and curvature, as will be discussed in section 1.3.3. Zhang et al. [ZHA 11] have designed a six-DoF wire-driven robotic manipulator for fetal surgery, namely to place a detachable silicone balloon in the fetal trachea for treatment of congenital diaphragmatic hernias. The robot is constituted of three units, each having two DoFs. The size is 2.4 mm in diameter. The contact force of the robot is controlled to be less than 0.3 N.

Figure 1.6. Hyper Finger [IKU 03]: a) seven-DoF slave manipulator at the end of a guide tube; b) close-up of the seven-DoF manipulator; c) master manip...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Intracorporeal Millirobotics

- Chapter 2: Intracorporeal Microrobotics

- Chapter 3: In Vitro Non-Contact Mesorobotics

- Chapter 4: Toward Biomedical Nanorobotics

- Bibliography

- Index