![]()

1

Introduction

De-en Jianga and Zhongfang Chenb

aChemical Sciences Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, USA

bDepartment of Chemistry, Institute for Functional Nanomaterials, University of Puerto Rico, USA

From the breakthrough discovery in 2004 [1], to the award of the Nobel Prize for Physics to Geim and Novosolov in 2010, it took only six years for graphene to reach the pinnacle of scientific research. However, this is not the first time that sp2 carbon has won a Nobel Prize. Remember that Smalley, Kroto, and Curl won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1996 for their discovery of fullerenes in 1985 [2]; only that took 11 years. What's more interesting is what the late Smalley said in his Nobel lecture: “Carbon has this genius of making a chemically stable two-dimensional, one-atom-thick membrane in a three-dimensional world. And that, I believe, is going to be very important in the future of chemistry and technology in general.” We have to admire his foresight of the explosion of interest in graphene 10 years later.

The fact that graphene won the Nobel Prize for Physics also reflects the community's focus on the physics aspect of graphene research. However, any large-scale application of graphene would undoubtedly rely on the chemistry of graphene. The expanding interest in graphene oxide through the Hummers method [3] or chemical-vapor deposition [4] approach to graphene synthesis are just two typical examples. The versatility of chemistry presents endless opportunities in graphene research.

Why do we focus on the theoretical perspectives of graphene chemistry? On one hand, there are books already discussing the experimental aspects of graphene chemistry; on the other hand, graphene provides an ideal proving ground for testing theoretical methods and computational imagination. In addition, sp2 or graphitic carbons are the basis of many important materials, such as carbon fibers for building cars and planes; activated carbons for supercapacitors; and graphite and hard carbons for lithium-ion batteries. Understanding graphene chemistry would also lay a foundation of understanding of complex carbonaceous materials. Therefore, the aim of this book is to deliver a comprehensive view of graphene chemistry from various theoretical and computational perspectives.

As a truly two-dimensional system, the honeycomb lattice of graphene has given rise to many interesting physical properties. However, no size is infinite in the real world and we eventually come to the edge of the graphene sheet just like the vast ocean greeting the shore line. Thus, we can expect that edge geometry will have a profound effect on the π-electronic structure.

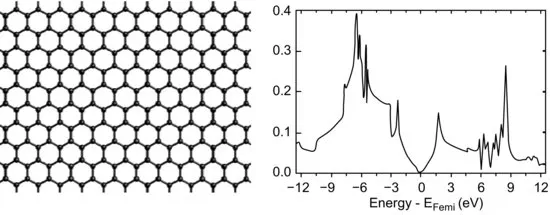

A chemist relates to graphene by thinking about benzene: graphene is nothing but fused benzene rings. The geometric character is the same: each carbon atom has sp2 hybridization and contributes one 2pz electron for π bonding. However, when contrasting the electronic structure of benzene with that of graphene, we can immediately see the difference: the benzene molecule has a large HOMO-LUMO gap (Figure 1.1), while graphene is a zero-gap semiconductor where the conduction band and the valence band touch at one point at the Fermi level (Figure 1.2). How does the electronic structure evolve from a large-gap six-membered ring to a zero-gap lattice of infinite number of fused rings? This is a rather intriguing question. It turns out that the chemical details matter. Let's take acenes, or linearly fused benzene rings, as an example. Quite a few theoretical papers have been devoted to examining the evolution of the electronic structure with the number of benzene rings in these interesting systems, starting with the earlier studies by Whangbo et al. [5] and Kivelson et al. [6]. In the experimental community, researchers have been trying to synthesize ever longer acenes. The record so far seems to be a nonacene derivative which has nine fused rings as its core [7]. Chapter 2 examines acenes or polyacenes by applying the effective valence bond model and the density-matrix-renormalization-group method, compared to density functional theory (DFT). More often than not, the linearly fused six-membered rings may not be as happy as alternating five-membered and seven-membered rings. This leads to a class of molecules called fused-azulenes or polyazulenes which also forms on the graphene edge due to reconstruction. Chapter 2 addresses this system too.

Extending acenes infinitely results in a ribbon with two zigzag edges. The width of the ribbon can also be further increased while preserving the two zigzag edges. What is unique about the zigzag edge is the edge state, as predicted by Fujita et al. [8–9] from the tight-binding method. This pioneering study has inspired many follow-up theoretical investigations and experiments. DFT calculations in particular, revealed that the edge state also possesses a radical-like chemical reactivity [10]. Chapter 4 examines the electronic, mechanical, and electromechanical properties of both zigzag-edged and armchair-edged graphene ribbons.

The uniqueness of the zigzag edge not only manifests itself in ribbons but also in nanographenes. This is fundamentally related to the inherent instability of the zigzag edge. Furthermore, this may be due to the difficulty that π-electrons have in forming localized double bonds since the consecutive zigzag edges do not support bond-length variation well [11]. In contrast, this is not a problem for armchair edges. The geometry-related π-electron distribution is captured by the Clar's sextet rule which seems to be particularly useful in predicting stable nanographenes [12] and ribbons. Chapter 3 seeks to understand aromaticity of graphene and graphene nanoribbons from the perspective of Clar's sextet rule, while Chapter 4 also briefly discusses the electronic structure of nanographenes or finite graphene flakes as the authors call them. Chapter 6 focuses on nanographene exclusively where the authors interrogates C–C bond length variation, orbital energies, and magnetization with the nanographene's size.

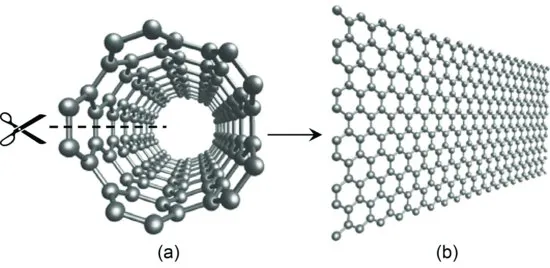

A most natural way to relate carbon nanotubes and graphene ribbons is probably to think of unzipping a carbon nanotube to a graphene ribbon. Amazingly, this idea, put forward for fun in 2007 [10] (Figure 1.3), was realized by two experiments two years later through plasma etching [13] and chemical oxidation [14]. Chapter 5 examines the mechanisms of various ways to cut open not only carbon nanotubes, but also graphene itself.

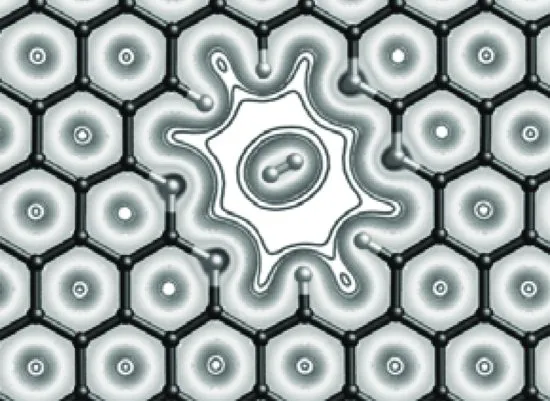

A straightforward way to utilize the one-atom thickness of graphene is to use it as a membrane, since a membrane's permeance is inversely proportional to its thickness. But a perfect graphene is impermeable to molecules as small as helium [15]. Hence, it is necessary to create holes to empower the graphene sheet for membrane separations; for example, the pore as shown in Figure 1.4 was computationally shown to be highly selective towards H2 [16] and CO2 [17]. More interestingly, this idea of using porous graphene to sieve gas molecules was recently experimentally confirmed through a clever setup [18]. Chapter 7 gives a detailed discussion of how to apply transition state theory to understand porous graphene and graphene nanomeshes for gas and isotope separations.

Using Lego bricks, a kid will let the imagination fly and build all sorts of things. Similarly, when given sp2-carbon building blocks, namely, fullerene, carbon nanotubes, and graphene, scientists can assemble them into sp2-hybridized carbon-based superarchitectures, such as fullerene polymers, nanotube clathrates, nanopeapods, nanobuds, nanofunnels, and nanofoams. Chapter 8 reviews the recent efforts in designing the prototypes of such materials and discusses their potential applications in electronics and energy storage.

Doping is an important topic in terms of graphene chemistry, as it is the major approach to opening and tuning the electronic band gap of graphene for device applications, and for modifying the graphene surface to improve reactivity and its interface with other materials for desired applications. Chapter 9 reviews different ways to dope graphene and their resulting changes in graphene's properties, as well as the characterization of doped graphenes and their applicati...