eBook - ePub

Confronting Suburbanization

Urban Decentralization in Postsocialist Central and Eastern Europe

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Confronting Suburbanization

Urban Decentralization in Postsocialist Central and Eastern Europe

About this book

This fascinating book explains the processes of suburbanization in the context of post-socialist societies transitioning from one system of socio-spatial order to another. Case studies of seven Central and Eastern Europe city regions illuminate growth patterns and key conditions for the emergence of sprawl.

- Breaks new ground, offering a systematic approach to the analysis of the global phenomenon of suburbanization in a post-socialist context

- Tracks the boom of the post-socialist suburbs in seven CEE capital city regions – Budapest, Ljubljana, Moscow, Prague, Sofia, Tallinn, and Warsaw

- Situates the experience of the CEE countries in the broader context of global urban change

- Case studies examine the phenomenon of suburbanization along four main vectors of analysis related to development patterns, driving forces, consequences and impacts, and management of suburbanization

- Highlights the critical importance of public policies and planning on the spread of suburbanization

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Confronting Suburbanization by Kiril Stanilov, Ludĕk Sýkora, Kiril Stanilov,Ludĕk Sýkora in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Challenge of Postsocialist Suburbanization

Luděk Sýkora and Kiril Stanilov

Introduction

Since the collapse of the communist regimes in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), cities in the former socialist countries have entered a period of dramatic transformation. One of the most important processes in the ensuing frenetic rearrangement of urban space has been the dispersal of urban functions beyond the edges of the compact city, into territories that experienced very little development during the socialist years (Sailer-Fliege, 1999; European Academy of the Urban Environment [EAUE], 2003; Hirt and Kovachev, 2006; Borén and Gentile, 2007; Stanilov, 2007a). There is widespread evidence that, since the mid-1990s, suburbanization has become the predominant mode of urban growth in postsocialist metropolitan areas (Kok and Kovács, 1999; Hamilton, Dimitrowska-Andrews, and Pichler-Milanović, 2005; Pichler-Milanović, 2005; Tammaru, 2005; Tosics, 2005; Tsenkova and Nedović-Budić, 2006; Hirt, 2007; Leetmaa and Tammaru, 2007; Novák and Sýkora, 2007; Ouředníček, 2007; Stanilov, 2007a; Sýkora and Ouředníček, 2007; Leetmaa, Tammaru, and Anniste, 2009; Krisjane and Berzins, 2011; Szirmai, 2011) and has a visible presence in medium-sized cities as well (Timár and Váradi, 2001; Parysek, 2004; Kotus, 2006; Matlovič and Sedláková, 2007; Marcińczak, 2012). Furthermore, studies suggest that postsocialist suburbanization is characterized by fragmented spatial patterns broadly associated with urban sprawl and its controversial environmental, economic, and social consequences (Nuissl and Rink, 2005; Pichler-Milanović, Gutry-Korycka, and Rink, 2007; Stanilov and Sýkora, 2012).

After a tempestuous decade of suburban explosion that lasted roughly from the second half of the decade 1990–2000 to the second half of the next decade – a period during which little concern was given to the impacts of unreservedly embracing urban dispersal as a principal growth strategy – it is time to pause and look back at the effects of such practices. The global financial and economic crisis that set in at the end of 2008 is a perfect opportunity to do so. It has given investors and developers a strong impetus to reassess their intentions and plans. More importantly, the crisis has opened up opportunities to consider alternatives to the neoliberal, free market policies and approaches adopted by postsocialist governments that have contributed to the extensive decentralization of CEE urban areas since the mid-1990s. The massive suburban development that started in the mid-1990 is an entirely new phenomenon for cities in the former socialist countries. Understanding its forms, conditions, causes, and consequences has become a great challenge for the general public and, specifically, for authorities responsible for the management of urban environment.

Our ultimate goal in this book is to explore and understand the processes of suburbanization in the specific context of postsocialist societies that are transitioning from one sociospatial order to another. By casting a light on the swift trajectory of suburbanization in CEE we hope to illuminate the key conditions for the emergence and proliferation of this phenomenon and to highlight the typical forms and features it takes in a dynamically evolving urban context. The explosion of suburban development in the former Eastern Bloc countries offers a rare chance to trace the impact of socioeconomic forces on the logic of (sub)urban space generation in conditions of rapid and radical social transformation. The fact that most CEE countries underwent a second round of complete societal makeover in the course of less than 50 years allows us to look at the region as a unique laboratory, in which the built environment has been molded so as to adjust to profound shifts in the basic principles of social organization.

Urbanization, Suburbanization, and Socioeconomic Order

A starting point for our exploration of postsocialist suburbanization is the juxtaposition of the trajectories, patterns, and underlying forces of urbanization and suburbanization under socialism and capitalism. These two opposing systems produced their own logic of urban space generation, which was shaped by contrasting approaches to setting the balance between the public and private realms. In this section we bring into focus the underlying bond between (sub)urbanization and socioeconomic order, which constitutes the theoretical foundation of our approach to understanding the phenomenon of postsocialist suburbanization.

Urban growth under socialism

Following the establishment of communist rule in the countries of CEE that fell under the influence of the Soviet Union after World War II, socialist government authorities imposed strict control over private property rights and economic activity, including the right to own, develop, rent, or trade land. The void created in the socialist economy by the imposition of strict constraints on private property rights and economic freedoms was filled by a commensurate expansion of the public sector through massive expropriation of the means of production. The socialist state became the main owner of land, as well as the main provider of goods, housing, and services through a centrally planned system of top-down hierarchical control exercised by the Communist Party. The emphasis was placed on planned production and controlled collective consumption as a more efficient and equitable system of resource utilization than the one based on balancing demand and supply through the actions of independent individual agents on the market.

Under these conditions, urbanization under socialism took on a strikingly different form by comparison to urban development in capitalist countries in terms of the allocation of human activities in space (French and Hamilton, 1979; Andrusz, Harloe, and Szelenyi, 1996; Enyedi, 1996; Gentile and Sjöberg, 2006; Sýkora, 2009). In contrast with the patterns of urbanization shaped by forces operating within a market economy that characterized development in capitalist countries, including those in CEE during the period up to World War II, the new socialist regimes promoted planned or “managed” urbanization (Musil, 1980; Smith, 1996) as the key instrument in the rational distribution and efficient utilization of economic and social resources.

A paramount development priority of the communist governments was the industrialization of the socialist economy. This goal absorbed the lion share of public resources, channeling them toward the formation of urban industrial hubs. The demand for labor in these growing industrial centers attracted waves of rural migrants pushed away from their villages by the collectivization of agricultural land and the mechanization of agricultural production (French and Hamilton, 1979; Musil, 1980). As a result, the socialist CEE countries experienced a dramatic boost in their urbanization rates. Between 1950 and 1990, the urban population of the region almost doubled, increasing its share from 38.3 to 66.5 percent, in contrast to an increase from 61.7 to 72.8 percent registered in the Western European countries over the same period (UN, 2011).

While the socialist system of central planning concentrated investments in selected cities and towns, which acted as regional and local growth poles, other areas and settlements were largely neglected. As a result, socialist urbanization was characterized by a sharp contrast between the growing, densely developed cities and towns, and the disproportionately smaller villages found within their surroundings, which featured a very limited range of economic activities. Despite the clear spatial separation of cities from their rural hinterlands, these two elements of the city regions were functionally related. Due to the decline in agricultural employment that resulted on the one hand from collectivization and modernization, on the other from the growth of industrial jobs in urban areas, an increasing share of rural residents started to commute to cities, using mass public transit systems – which consist of busses, trains, underground and trams – as a main form of transportation. The rural to urban commuting was further impacted by the discrepancy between jobs and housing availability. As the growth of urban jobs was not paralleled by a corresponding supply of new housing, a significant portion of the rural population employed in nearby cities retained its rural residence – a phenomenon described as under-urbanization (Murray and Szelenyi, 1984; Szelenyi, I., 1996).

As the highest priorities were placed on public ownership of resources, centralized delivery of goods and services, and collective consumption, the socialist system generated compact urban environments characterized by high-density residential districts, extensive industrial zones, fairly well-developed networks of public transit and infrastructure, and hierarchically organized provision of space for retail and service facilities. Once land development was completely under the control of state authorities, government policies concentrated the spatial allocation of public investments in three target areas within cities: (1) the expansion of industrial capacity through the development of new and the extension of existing industrial zones; (2) the development of massive housing estates at the urban edges; and (3) the redevelopment of city centers as monuments of the social and economic prosperity achieved under the leadership of the communist regime.

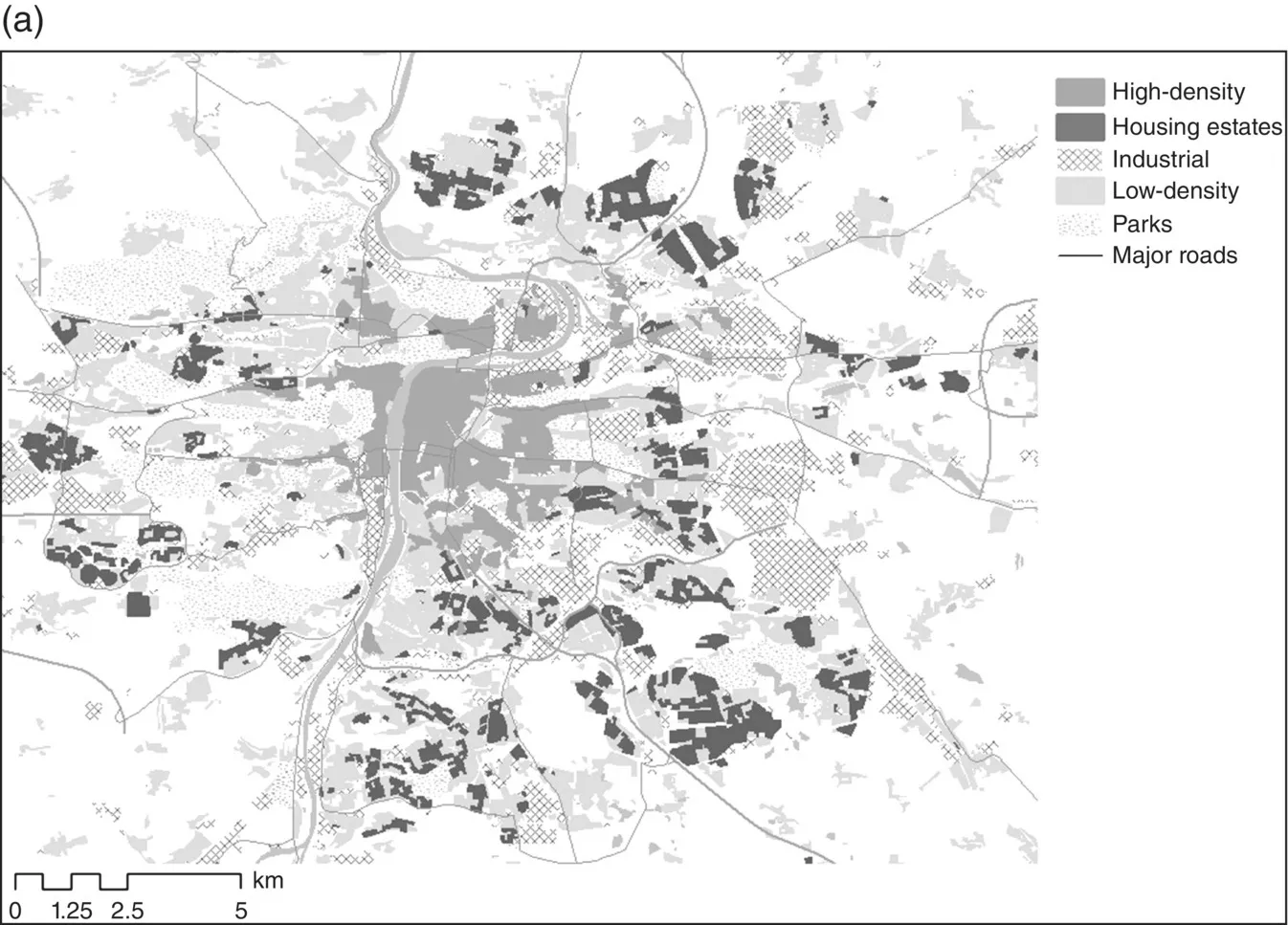

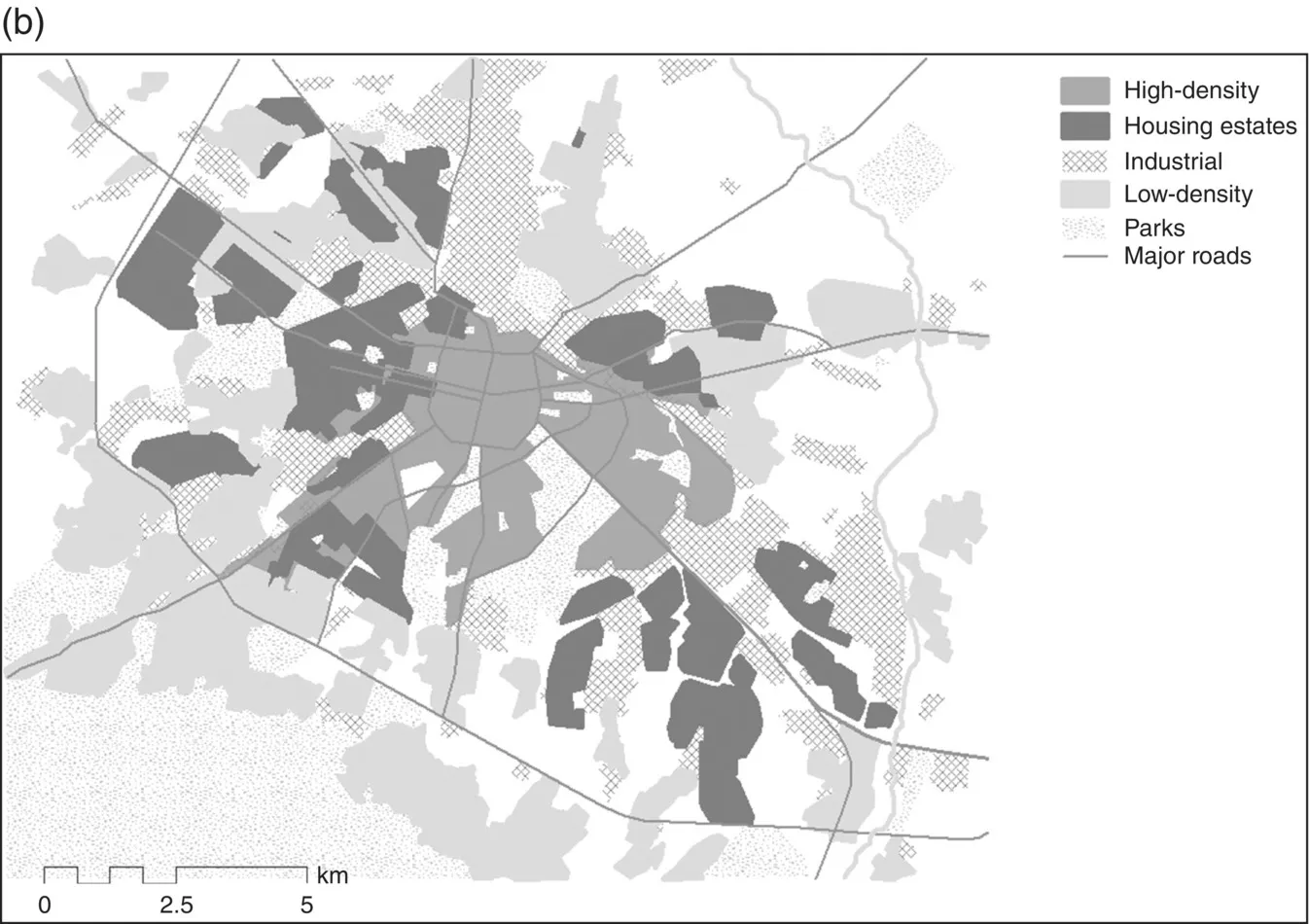

Most of the investments and new construction were concentrated in vacant areas found within the existing urban fabric and on the edges of the built-up urban cores. Most of the new residential development during the socialist period was in the form of large housing estates planned as urban extensions at the urban edge, side by side with newly established industrial zones (Figure 1.1). Besides housing, these estates provided a selection of local services in carefully planned retail, educational, medical, and recreational facilities. We should note that this model of urban expansion through high-density extensions in the form of housing estates was not a unique invention of the socialist states. It was embraced by many governments in postwar Europe (Power, 1998; Rowlands, Musterd, and van Kempen, 2009) and spread to other parts of the world. In the Eastern Bloc countries, however, it was adopted extensively and universally, as the key housing policy of the socialist states. A main reason for this was the fact that the modernist concept of urban growth through high-density extensions suited perfectly the communist ideology of centralized control over the production, supply, and allocation of housing and urban services.

Figure 1.1a Location of socialist housing estates and industrial zones in Prague.

Source: the authors.

Figure 1.1b Location of socialist housing estates and industrial zones in Sofia.

Source: the authors.

The new socialist housing estates were only rarely located at a distance from the compactly built-up urban areas. They were planned as an integral part of the socialist city, functionally integrated with industrial zones and service nodes through public mass transit infrastructure. Under these circumstances, the socialist cities developed as fairly compact urban environments with sharply delineated physical boundaries (Ioffe and Nefedova, 1998). Thus, while most western cities began to deconcentrate in the postwar decades, the socia...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Studies in Urban and Social Change

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Illustrations

- Glossary

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Preface

- 1 The Challenge of Postsocialist Suburbanization

- 2 Urban Sprawl on the Danube

- 3 Confronting Suburbanization in Ljubljana

- 4 Suburbanization of Moscow’s Urban Region

- 5 Prague

- 6 Sprawling Sofia

- 7 Suburbanization in the Tallinn Metropolitan Area

- 8 Lessons from Warsaw

- 9 Postsocialist Suburbanization Patterns and Dynamics

- 10 Managing Suburbanization in Postsocialist Europe

- Index

- End User License Agreement