![]()

Part I

Bacteria

![]()

Chapter 1

Bacillus anthracis: Anthrax

Markus Antwerpen, Paola Pilo, Pierre Wattiau, Patrick Butaye, Joachim Frey, and Dimitrios Frangoulidis

1.1 Introduction

Anthrax is an acute infection, caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis. This zoonosis can be transmitted from grass-eating animals or their products to humans. However, it should be noted also that B. anthracis has all the characteristics of an environmentally adapted bacterium. Normally, anthrax occurs in 95% of all human reported cases as cutaneous anthrax, caused by bacteria penetrating the skin through wounds or micro fissures, but the bacterium can also manifest in the mouth and the intestinal tract. Infection of the lungs after inhalation of the spores is very rarely observed [1, 2].

B. anthracis is listed as a category A bioterrorism agent by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [3]. Besides the knowledge that B. anthracis has a history as a biological weapon in different national military programs, the general public became aware of this pathogen in 2001 when specially processed spore-filled letters were sent across the United States of America, killed five persons and infected up to 26. Since that time “white powder” became a synonym for the bioterroristic threat all over the world. In addition to this special aspect, anthrax is still an endemic disease in many countries and sporadically occurs all over the world [2]. Today, imported wool or hides from ruminants (e.g., goats, sheep, cows) could be contaminated with spores and occasionally lead to infections in industrial (“wool sorting factory”) or private settings (Bongo drums) in countries where the disease is absent or infrequent [4, 5].

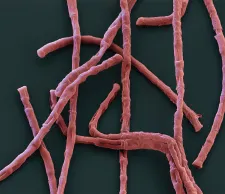

1.2 Characteristics of the Agent

B. anthracis is a nonmotile, Gram-positive, spore-forming aerobic rod, arranged in long chains within the tissue. Sporulation occurs in the presence of free oxygen and endospores develop in central positions that are considered as infectious particles. They are extremely resistant to harsh environmental conditions, such as heat, dehydration, pH, desiccation, chemicals, irradiation, or ice. In this dormant state, they can survive up to decades or centuries in the environment without loss of virulence [1, 2]. Robert Koch discovered this agent and its sporulated form in 1877 and demonstrated for the first time his so-called postulates that establish a causal relationship between a pathogen and a disease [6].

1.3 Diagnosis

1.3.1 Phenotypical Identification

B. anthracis belongs to the B. cereus group, which comprises six closely related members: B. anthracis, B. cereus, B. mycoides, B. pseudomycoides, B. thuringiensis, and B. weihenstephanensis. These species are phylogenetically and phenotypically closely related and their phenotypical identification can be complex, especially because some isolates may display unusual biochemical and/or genetic properties that complicate their distinction. Furthermore, several of these species and also yet-undefined species of this group are normal contaminants in environmental samples such as soil or dust.

Phenotypical identification is the classical method of identification in routine laboratories. Some simple characteristics have been useful for distinguishing between different Bacillus species, but they have limitations particularly in distinguishing between B. cereus and B. anthracis [7]. The following sections focus on the different methods and highlight their advantages and disadvantages.

1.3.2 Growth Characteristics

B. anthracis is a Gram-positive aerobic spore-forming rod which grows well on all types of blood-supplemented agars. After cultivation at 37 °C overnight, B. anthracis shows the following morphological characteristics [2]:

- No hemolysis on blood agars;

- Spike-forming (see Figure 1.1);

- “Sticky” colonies (see Figure 1.2);

- Medusa head;

- While growing on Cereus-Ident agar (Heipha, Germany), it forms colonies that are silver-gray, silky-shiny, and polycyclic without any pigmentation [8]. As an alternative, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-polymyxin-blood agar (TSPB agar) can be used, containing several antibiotics and resulting in a high selectivity against Gram-negative bacteria.

Even if only some of these features are observed, the results should be considered as suspicious for B. anthracis and further analysis for differentiation should be mandatory.

1.3.3 Antibiotic Resistance

The so-called “string of pearls”/“Perlschnur” test is based on the fact that most of the strains isolated in nature are sensitive to penicillin (in contrast to B. cereus isolates) and show a special stress form of the bacteria when it is faced with sublethal doses of the antibiotic. This very simple test is still used today to get a first very easy confirmation of suspicious colonies.

The determination of the pattern of antibiotic resistance is of utmost interest, primarily for the assessment of a potential release of bacteria with a bioterroristic background [9], with genetically modified strains, and to detect rarely occurring natural resistances. To establish the antibiotic resistance profiles of strains, the minimum inhibition concentrations (MICs) have to be tested. They are fixed by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). The CLSI publishes guidelines containing protocols and breakpoint values to evaluate antibiotic resistances profiles [10, 11].

1.3.4 Phage Testing and Biochemistry

Phage testing and biochemical tests are methods that are still in use today in veterinary diagnostic laboratories. Biochemical tests do not lead to a clear and valuable result for differentiating B. anthracis from B. cereus, while phage testing with bacteriophage gamma is more specific. The feature of sensitivity of B. anthracis to gamma phage is still used for identification although exceptions were described in this case, too. In former times veterinary laboratories used a mouse inoculation test for confirmation. When all phenotypic characteristics were present and the phage test was positive, and finally the mouse died within one day after intraperitonal inoculation, and bacillus-like bacteria were seen on colored blood samples, the isolated bacterium was seen as a virulent strain of B. anthracis.

1.3.5 Antigen Detection

Newer methods have been developed for the identification of B. anthracis from the presence of specific surface proteins. Such systems are encapsulated in lateral flow assays, commercialized for example by the companies Tetracore or Cleartest. Even for these assays, some isolates of B. cereus that result in a weak positive signal have been described. Based on their low sensitivity, it is recommended to use this kind of experiment only as a confirmation test of suspect colonies rather than for the detection of B. anthracis in environmental samples, since the concentration of bacteria may not be adequate in such samples. The advantage of such a test is the ease of specimen handling. Suspicious material is rubbed into a buffer and the suspension is dropped onto the cartridge. After 15 min of incubation, the results can be evaluated like a pregnancy test. If the test is used for checking questionable colonies (especially when they show no hemolysis on blood agar), it gives very specific results in the identification of B. anthracis.

1.3.6 Molecular Identification

1.3.6.1 Virulence Plasmid pXO1

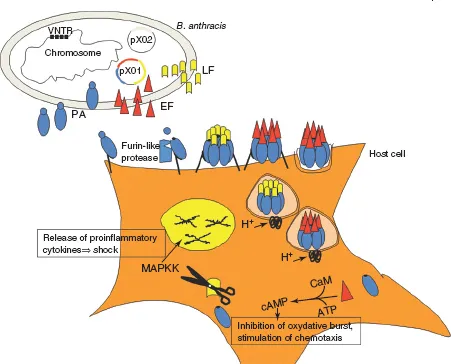

The virulence plasmid pXO1 is said to be “anthracis-specific.” The genes coding for “lethal factor” (LF; lef), “edema factor” (EF; cya), and “protective antigen” (PA; pagA) are normally present on this plasmid and are major virulence factors of B. anthracis (see Figure 1.3). Due to this, most of the commercially available PCR diagnostic kits target sequences of these genes to detect B. anthracis. Recently, strains of B. cereus could be isolated from patients presenting the clinical symptoms of an “anthrax-like” disease. In these strains at least one of the above-mentioned genes could be observed. Therefore, this plasmid cannot be used as a specific marker for B. anthracis, thus complicating the definition and differentiation of species belonging to the B. cereus group [7, 12–16]. However, from a clinical point of view, it is not important which species is present or not if these virulence genes are present and the patient’s symptoms are similar to those caused by B. anthracis.

1.3.6.2 Viru...