![]()

PART I

Lay of the Land

![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Need for Critical Thinking in Clinical Practice

Decision making is at the heart of clinical practice. You may have to decide how to assess a client’s depression. What sources of information will you draw on and what criteria will you use to evaluate their accuracy? Will you rely on your intuition? Will you ask your client to complete the Beck Depression Inventory? Will you talk to family members and take a careful history? Will it help you to understand your client’s depression if you provide a psychiatric diagnosis? Or you may have to decide how to help parents increase positive behaviors of their four-year-old child. What sources of information will you use? How can you locate valuable guidelines regarding the most effective methods? What criteria will you use to review the evidentiary status of a claim such as: “Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is due to a biochemical imbalance”? Think back to a client with whom you have worked. Which of the following 10 criteria did you use to make decisions (Gambrill & Gibbs, 2009)?

1. Your intuition (gut feeling) about what will be effective.

2. What you have heard from other professionals in informal exchanges.

3. Your experience with a few cases.

4. Your demonstrated track record of success based on data you have gathered systematically and regularly.

5. What fits your personal style.

6. What is usually offered at your agency.

7. Self-reports of other clients about what is helpful.

8. Results of controlled experimental studies (data that show that a method is helpful).

9. What you are most familiar with.

10. What you know by critically reading the professional literature.

In addition to complex decisions that involve collecting and integrating diverse sources of data, scores of smaller decisions are made in the course of each interview, including moment-to-moment decisions about how to respond. Options include questions, advice, reflections, interpretations, self-disclosures, and silence. Decisions are made about what outcomes to focus on, what information to gather, what intervention methods to use, and how to evaluate progress. The risks of different options must be evaluated, and probabilities must be estimated. Judgmental tasks include deciding on causes and making predictions. You may have to decide whether a child’s injuries are a result of parental abuse or were caused by a fall (as reported by the mother). You will have to decide what criteria to use to make this decision and when you have enough material at hand. If a decision is made that the injuries were caused by the parent, a prediction must be made as to whether the parent is likely to abuse the child again. Errors that may occur include:

- Errors in description. (Example: Mrs. V. was abused as a child when she was not.)

- Errors in detecting the extent of covariation. (Example: All people who are abused as children abuse their own children.)

- Errors in assuming causal relationships. (Example: Being abused as a child always leads to abuse of one’s own children.)

- Errors in prediction. (Example: Insight therapy will prevent this woman from abusing her child again when this is not true.)

The events of the past few years continue to illustrate the need for critical thinking in clinical practice. During these years there has been a continuing parade of revelations, including hiding of negative trials, hiding adverse effects of medications, creating bogus categories of illness, overmedicating young children and the elderly with antipsychotics, and related conflicts of interest. (See Gambrill, 2012a.) Academic researchers, including some heads of psychiatry departments at prestigious universities, have been shown to be in the pay of pharmaceutical companies while underreporting this income to their universities, sometimes by millions of dollars. Ioannidis (2005) argues that most research findings reported in the biomedical literature are false. Hiding alternative views is common, such as failure to describe a view of anxiety in social situations as a learned reaction created by a unique learning history and/or arousal threshold (Gambrill & Reiman, 2011). Anxiety in social situations is typically proclaimed to be a psychiatric disorder. Did you know that this “disorder” was created by Cohn and Wolfe, a public relations firm hired by a pharmaceutical company (Moynihan & Cassels, 2005)?

THE IMPORTANCE OF THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT DECISIONS

Clinical practice allows a wide range of individual discretion: how to frame problems, what outcomes to pursue, when to stop collecting information, what risks to take, what criteria to use to select practice methods, and how to evaluate progress. The privacy of clinical practice (rarely is it observed by other clinicians) allows unique styles, which may or may not enhance the accuracy of decisions. Use of vague evaluation procedures may maintain styles that are not optimal. Clients may be harmed rather than helped if we do not think critically about the decisions we make. Are they well-reasoned? Are they informed by related research? Have we avoided being bamboozled into accepting bogus claims about the effectiveness of a method? As Karl Popper (1994) points out, “There are always many different opinions and conventions concerning any one problem or subject-matter. . . . This shows that they are not all true. For if they conflict, then at best only one of them can be true” (p. 39). The following 13 findings suggest that clinical decisions can be improved:

1. There are wide variations in practices (e.g., see Goodman, Brownlee, Chang, & Fisher, 2010).

2. Most services provided are of unknown effectiveness. There has been little rigorous critical appraisal of most variations in practices and policies in relation to their outcomes (e.g., do they do more good than harm?).

3. Clients are harmed as well as helped. Consider, for example, the death of a child in “rebirthing therapy” (Janofsky, 2001; see also Diaz & de Leon, 2002; Goulding, 2004; Moncrieff & Leo, 2010; Ofshe & Watters, 1994; Sharpe & Faden, 1998; Whitaker, 2010).

4. Intervention methods found to be harmful continue to be used (e.g., Petrosino, Turpin-Petrosino, & Buehler, 2003).

5. Assessment methods shown to be invalid continue to be used (e.g., Hunsley, Lee, & Wood, 2003; Thyer & Pignotti, in press).

6. Methods that have been found to be effective are often not offered to clients (e.g., Jacobson, Foxx, & Mulick, 2005).

7. There are large gaps between claims of effectiveness and evidence for such claims (Greenberg, 2009; Ioannidis, 2005).

8. Good intentions are relied on as indicators of good outcomes.

9. Journalists’ exposés of avoidable harms are common.

10. Avoidable errors are common (e.g., DePanfilis, 2003; Kaufman, 2006).

11. Licensing and accreditation bodies such as the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) and the Council on Social Work Education rely on surrogates of competence and quality of professional education, such as the diversity of faculty and size of faculty, their degrees, and their experience (Gambrill, 2002; Stoetz, Karger, & Carrilio, 2010).

12. Clients are typically not informed regarding the evidentiary status of recommended services (e.g., that there is no evidence that these are effective or do more good than harm; Braddock, Edwards, Hasenberg, Laidley, & Levinson, 1999; Cohen & Jacobs, 1998; Gottlieb, 2003).

13. There seems to be an inverse correlation between growth of the helping professions and problems solved.

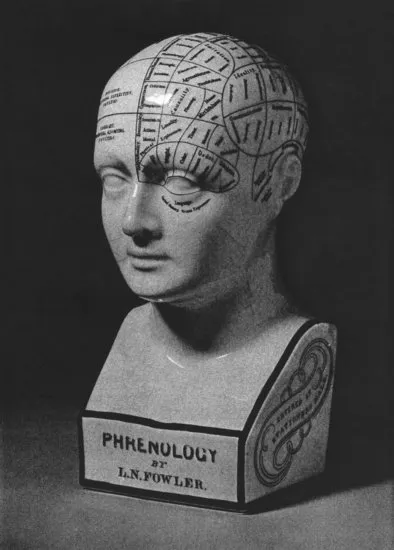

The history of the helping professions shows that decisions made may do more harm than good. Consider the blinding of 10,000 babies by the standard practice of giving them oxygen at birth (Silverman, 1980). Scared Straight programs designed to decrease delinquency have been found to increase it (Petrosino, Turpin-Petrosino, & Buehler, 2003). Many clinicians carry out their practice with little or no effort to take advantage of practice-related research describing the evidentiary status of different interventions. Gaps between knowledge available and what was used were a key reason for the development of evidence-based practice and care (Gray, 2001a). The histories of the mental health industry, psychiatry, psychology, and social work are replete with the identification of false causes for personal troubles and social problems. Complex classification systems with no empirical status such as those based on physiognomy (facial type) and phrenology (skull formation) were popular, including the creation of metal phrenological hats to aid in diagnosis (Gamwell & Tomes, 1995; McCoy, 2000). (See Exhibit 1.1.)

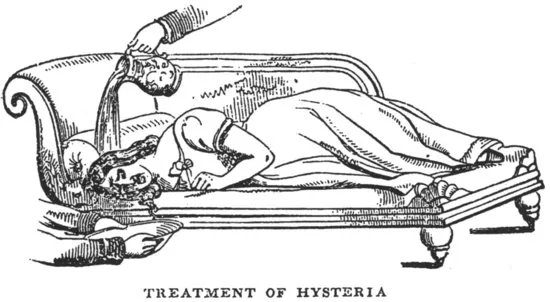

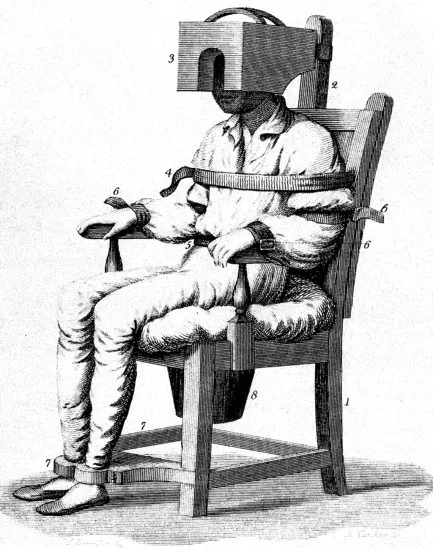

Reviews of the history of psychiatry reveal a long list of intrusive interventions that can best be described as torture (e.g., Scull, 2005; Valenstein, 1986). Consider Darwin’s chair, in which a patient was spun until bleeding from his or her nose. Water-based interventions were a popular strategy (see Exhibit 1.2). A former patient, Ebenezer Haskell, said he witnessed the spread-eagle method while in Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane. “A disorderly patient is stripped naked and thrown on his back, four men take hold of the limbs and stretch them out at right angles, then the doctor or some one of the attendants stands up on a chair or table and pours a number of buckets full of cold water on his face until life is nearly extinct, then the patient is removed to his dungeon cured of all diseases” (cited in Gamwell & Tomes, 1995, p. 63). The remedy of the tranquilizing chair is shown in Exhibit 1.3. Epidemiologists bring to our attention different rates of use of certain kinds of interventions, such as the higher number of hysterectomies in the United States as compared with Great Britain. Such differences may reflect actual need, or they may result from influences that conflict with client interests (such as an overabundance of surgeons or a tendency to think for clients rather than inform them fully and let them make their own decisions). Variations in services provided for the same concern were another reason for the development of evidence-based medicine and health care (Gray, 2001b; Wennberg, 2002).

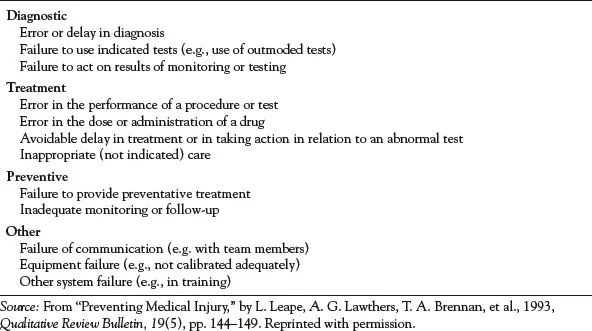

The exposure of avoidable errors and harming in the name of helping is a topic of concern to journalists as well as investigators in a variety of fields, as illustrated by reports of children maltreated by their foster parents (e.g., DePanfilis, 2003; Pear, 2004); abuse of patients in facilities that purport to help them, such as group homes for the so-called mentally ill (e.g., Levy, 2003); and neglectful practices in hospitals and nursing homes (e.g., Delamothe, 2011; Mooney, 2011). Preventable medical error is responsible for 98,000 deaths per year and 99,000 deaths result from hospital-acquired infections per year. Exhibit 1.4 illustrates types of errors. What would be considered an error today might have been considered common (and good practice) years ago. For example, many people who entered a mental hospital in the 1950s and spent the rest of their lives there should not have been hospitalized in the first place. Many errors reflect a confirmatory bias (seeking only data that support favored views; Nickerson, 1998). Imagine that you are a community organizer in a low-income neighborhood and believe that new immigrants moving into the neighborhood are the least likely to become active in community advocacy efforts. Because of this belief, you may concentrate your attention on long-term residents. As a result, new resident immigrants are ignored, with the consequence that they are unlikely to become involved. This will strengthen your original belief.

The very nature of clinical practice leaves room for many sources of error. Decisions must be made in a context of uncertainty; the criteria on which decisions should be made are in dispute, and empirical data about the effectiveness of different intervention options are often lacking. Clients seek relief from suffering, and professionals hope to offer it; there is a pressure from both sides to view proposed options in a rosy light. Some errors result from a lack of information about how to help clients. Empirical knowledge related to clinical practice is fragmentary, and theory must be used to fill in the gaps. Other errors result from ignorance on the part of individual clinicians—that is, knowledge (defined here as information and procedural know-how that reduce or reveal uncertainty) is available but is not used. This lack of knowledge and skill may be due to inexperience or inadequate training. Errors also result from lack of familiarity with political, economic, and social influences on professions such as psychiatry, psychology, and social work (e.g., Cohen & Timimi, 2008). The interpersonal context within which counseling occurs offers many potential opportunities for mutual influence that may have beneficial or dysfunctional effects, as described in Chapter 2. Errors may occur because of personal characteristics of the clinician, such as excessive need for approval.

Avoidable errors may result in (1) failing to offer help that could be provided and is desired by clients, (2) forcing clients to accept practices they do not want, (3) offering help that is not needed, or (4) using procedures that aggravate rather than alleviate client concerns (that is, procedures that result in iatrogenic effects; e.g., Sharpe & Faden, 1998). Such errors may occur in all phases of clinical practice: assessment, intervention, and evaluation. Errors may occur during assessment by overlooking important data, using invalid measures, or attending to irrelevant data; during intervention by using ineffective methods; and during evaluation by using inaccurate indicators of progress. Reliance on irrelevant or inaccurate sources of data during assessment may result in incorrect and irrelevant accounts of client concerns and recommendation of ineffective or harmful methods. Important factors may not be noticed. For example, a clinician may overlook the role of physiological factors in depression. Depression is a common side effect of birth control pills and is also related to hormonal changes among middle-aged women. Failure to consider physical causes may result in inappropriate decisions. Failure to seek information about the evidentiary status of methods may result in use of an ineffective method. We may fail to recognize important cues or attend to irrelevant content. Errors may result from reliance on questionable criteria such as anecdotal experience to evaluate the accuracy of claims, as discussed in Chapter 4.

Given the role of decision making in clinical practice and the variety of factors that influence the quality of decisions, it is surprising that more attention is not devoted to this content in professional training. Meehl’s book C...