![]()

Chapter 1

Advocating for a Bold Brand of Teacher Leadership

Teacher leaders must be producers of solutions rather than just implementers of someone else's. —Lori Nazareno

Almost a decade ago, Jennifer York-Barr and Karen Duke put together a comprehensive review of teacher leadership, a new field of inquiry at the time of this review's publication. It is a must-read, even for those who are not inclined to read academic journals. They describe a great deal about the dimensions and characteristics of teacher leadership, but point out that although the literature is “relatively rich” in regard to classroom experts' potential to lead, it is light on the “evidence of such effects.”1 Nevertheless, York-Barr and Duke thoughtfully outline how teacher leadership has evolved over time, pointing to three distinct waves.

In Wave 1, teachers served in formal roles as grade-level chairs, department heads, or union representatives and took on managerial roles designed to “further the efficiency of school operations.”2 This means that teachers did the work that administrators did not want to perform.

In Wave 2, teachers took on instructional roles, helping to implement the mandated curriculum, leading staff development workshops, and mentoring new recruits or showing them the ropes as “buddies.” These teacher leader roles have become a bit more commonplace today, especially with the formalization of induction programs for new recruits. But as other researchers have made clear, few school districts implement these programs with much fidelity. For example, although more new recruits have access to induction programs, few programs have the qualities (that is, mentoring by trained veterans, a reduced teaching load, and so on) known to improve the retention of teachers in the classroom.3

And in Wave 3, teachers began to lead what are now called professional learning communities (PLCs) in an effort to support collaboration and continuous learning among themselves. But as Andy Hargreaves has noted, “many professional learning communities can be horrifically stilted caricatures of what they are really supposed to be.”4 Most administrators do not know how to embrace the “P” of PLC. They do not understand or know how to cultivate professionalism inside their school, and teachers often do not, as a collective, know what high-functioning PLCs look like.

York-Barr and Duke do point out that “professional norms of isolation, individualism, and egalitarianism” often undermine teacher leadership.5 But they do not address the fact that for most of teaching's past, administrators and other powerful political and policy leaders of our nation's public school system have wanted all of those who teach to play the same roles. For example, a National Board Certified Teacher (NBCT) from the Center for Teaching Quality (CTQ) Collaboratory, whose recent essay describing a school of the future garnered a national award, shared with us that her principal directly told her not to pursue anything outside of her classroom. The reason is simple, but also troubling: if all teachers do primarily the same thing, they are easier to manage.6

A New Wave of Teacher Leadership

Examples like those just given are why we are advocating for a Wave 4 of teacher leadership—in which those who teach have time and space to lead, and are rewarded for leading, well beyond their district, state, and nation. As Lori Nazareno (whom you will get to know in Chapter Six)—an NBCT who incubated a teacher-led school in Denver, pushing both her district and her union to think differently about reform—reminded us, “In Wave 4, teacher leaders must be producers of solutions rather than just implementers of someone else's.” We must make this happen—and here are a couple of compelling reasons.

First, powerful evidence speaks volumes about how teacher leadership can make a significant difference for students. Almost twenty-five years ago Susan Rosenholtz's landmark study concluded that “learning-enriched schools” were characterized by “collective commitments to student learning in collaborative settings . . . where it is assumed improvement of teaching is a collective rather than individual enterprise, and that analysis, evaluation, and experimentation in concert with colleagues are conditions under which teachers improve.”7 Other researchers have found that students achieve more in mathematics and reading in schools with higher levels of teacher collaboration.8 And economists, using sophisticated statistical methods and large databases, have recently concluded that students score higher on achievement tests when their teachers have had opportunities to work with colleagues over a longer period of time and to share their expertise with one another.9 Teachers themselves put an exclamation point on these empirical findings: in a 2009 MetLife survey of American teachers, over 90 percent of teachers reported that their colleagues contribute to their own individual effectiveness.10

The current crisis in education should bring us to reexamine the essential core of teaching and learning for all students.

Second, the challenges facing our public schools cannot be met with all teachers serving in the same narrow roles designed for a bygone era. Consider the complexity of teaching to our nation's Common Core State Standards and the personalized learning systems required to prepare a diverse mix of fifty-five million (and growing) students for career and college in a global economy. Then think about today's one in five students who do not speak English as their primary language; by 2030 the number will double to 40 percent. Almost 25 percent of our nation's public school students, because of their families' devastating economic situations, are at risk of not meeting the higher academic standards imposed by the new economy. One in ten of our nation's children live in what sociologists call deep poverty.* And deep poverty creates early life stresses in children—a fact proven by neuroscientists who have shown how anxiety and tensions can “disrupt the healthy growth of the prefrontal cortex,” inhibiting the cognitive development that is critical to academic learning.11 Effectively addressing these out-of-school issues requires more teacher solutions—a special brand of pedagogical and policy ideas generated by classroom practitioners who regularly serve students and families.

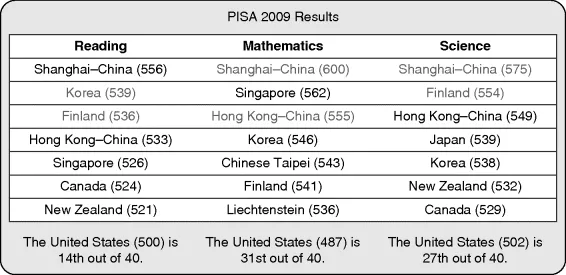

And finally, such top-performing nations as Finland (see Chapter Nine) and Singapore have built their success on reducing standardized testing and increasing curriculum flexibility. Both of these nations promote, explicitly through national policy, more teacher professionalism and greater connectivity between those who teach and those who make policy. In Finland and Singapore, which invest heavily in teacher education, there is no such thing as a shortcut into teaching. Unlike in the United States, these nations do not focus mainly on recruiting more talent into teaching for a few years and statistically identifying those who generate student test score gains. Instead, they invest deeply in preservice preparation and demonstrate serious respect for teachers by promoting the importance of teaching for a career. Finland and Singapore also, through the way teachers organize themselves into PLCs, capitalize on teachers' capacity to lead.

And their results are real.

But there is more.

Futurists claim that U.S. schools will face more, not fewer, economic disparities among the students they serve, and must organize themselves differently—including more expansive leadership, new forms of assessment, and “diverse learning agent roles.”12 Individual school principals, even with a small band of assistants, do not have the know-how or the capacity to do all that must be done as schools morph into 24/7 “hubs” for integrated academic, social, and health services. The kinds of roles teacher leaders must play include building and scoring new assessment tools tied to internationally benchmarked standards, integrating digital media into a more relevant curriculum for constantly wired students, and partnering with community organizations. And although technology can allow students to engage in personalized learning experiences like never before, it will take well-prepared, expert teachers to offer them deep educational opportunities. A special brand of teacher leader—one who has skills in spanning organizational boundaries—will be required to meet the demands posed by twenty-first-century schooling.

Moving Past Outdated Structures and Inadequate Solutions

Dramatically improving public education for all will take both collective action and the discretionary judgment of many expert teachers, not just a few. Teaching and learning, now and in the future, are as complicated as the work of a federal judge who is issuing a decree on immigration law in contentious communities in Arizona and South Carolina; or the efforts of doctors who are interpreting an array of blood tests, MRI results, and family medical histories to determine how to treat a brain tumor. To best serve children and their families, we need far different approaches to organizing our schools—and we must enlist the help of our 7.2 million educators in both the K–12 and higher education sectors. And we should call on teacherpreneurs in particular.

However, today's conceptions of America's teacher leaders remain too narrow—often upholding the existing, and quite archaic, school structures. Educators rightly have called for teacher leaders to serve as resource providers (helping novices set up their classroom); instructional specialists (studying research-based classroom strategies and sharing findings with colleagues); curriculum experts (helping colleagues use common pacing charts and develop shared assessments); classroom supporters (demonstrating a lesson, coteaching, or observing and giving feedback); and school leaders (serving on committees or acting as grade-level or department chairs).13 These are important roles, don't get us wrong, but they barely get us out of Wave 2 teacher leadership. Teachers are sometimes given a chance to lead, but they are expected to do so only inside the confines of their school or district. Granted, our public education system still needs to develop future Wave 2 teacher leaders. But students and their families and communities need teacher leaders who initiate change, much like today's reformers who are calling for education entrepreneurs to improve teaching and learning. Unlike the teacherpreneurs featured in this book, however, education entrepreneurs are not necessarily required to have deep, successful classroom experience or knowledge of students and their families.

Granted, teacher leadership has become more popular of late. Several years ago, a group of educators pieced together a string of domains and standards for teacher leaders—the Teacher Leader Model Standards—designed to delineate the knowledge, skills, and competencies that teachers need to assume leadership roles in their school, district, and profession. And some universities have taken steps forward by using these standards to create innovative programs—as is the case wit...