![]()

Chapter 1

A Highly Personal Endeavor

What Do You Want to Own?

Man the living creature, the creating individual, is always more important than any established style or system.

—Bruce Lee

The stock market is a curious place because everyone participating in it is loosely interested in the same thing—making money. Still, there is no uniform path to achieving this rather uniform goal. You may be only a few mouse clicks away from purchasing the popular book The Warren Buffett Way,1 but only one man has ever truly followed the path of Warren Buffett. In investing, it is hard enough to succeed as an original; as a copycat, it is virtually impossible. Each of us must carve out a personal way to investment success, even if you are a professional investor.

That said, great investors like Ben Graham, Seth Klarman, and Warren Buffett have much to teach us, and we have much to gain by learning from them. One of the masters’ key teachings is as important as it is simple: A share of stock represents a share in the ownership of a business. A stock exchange simply provides a convenient means of exchanging your ownership for cash. Without an exchange, your ownership of a business would not change. The ability to sell your stake would be negatively affected, but you would still be able to do it, just as you can sell your car or house if you decide to do so.

Unfortunately, when we actually start investing, we are inevitably bombarded with distractions that make it easy to forget the essence of stock ownership. These titillations include the fast-moving ticker tape on CNBC, the seemingly omniscient talking heads, the polished corporate press releases, stock price charts that are consolidating or breaking out, analyst estimates being beaten, and stock prices hitting new highs. It feels a little like living in the world of Curious George, the lovable monkey for whom it is “easy to forget” the well-intentioned advice of his friend. My son loves Curious George stories, because as surely as George gets into trouble, he finds a way out of trouble. The latter doesn’t always hold true for investors in the stock market.

Give Your Money to Warren Buffett, or Invest It Yourself?

I still remember the day I had saved the princely sum of $100,000. I had worked as a research analyst for San Francisco investment bank Thomas Weisel Partners for a couple of years and in 2003 had managed to put aside what I considered to be an amount that made me a free man. Freedom, I reasoned, was only possible if one did not have to work to survive; otherwise, one was forced into a form of servitude that involved trading time for food and shelter. With the money saved, I could quit my job, move to a place like Thailand, and live on interest income. While I wisely chose not to exercise my freedom option, I still had to find something to do with the money.

I dismissed an investment in mutual funds quite quickly because I was familiar with findings that the vast majority of mutual funds underperformed the market indices on an after-fee basis.2 I also became aware of the oft-neglected but crucial fact that investors tended to add capital to funds after a period of good performance and withdraw capital after a period of bad performance. This caused investors’ actual results to lag significantly behind the funds’ reported results. Fund prospectuses show time-weighted returns, but investors in those funds reap the typically lower capital-weighted returns. A classic example of this phenomenon is the Munder NetNet Fund, an Internet fund that lost investors billions of dollars from 1997 through 2002. Despite the losses, the fund reported a positive compounded annual return of 2.15 percent for the period. The reason? The fund managed little money when it was doing well in the late 1990s. Then, just as billions in new capital poured in, the fund embarked on a debilitating three-year losing streak.3 Although I had felt immune to the temptation to buy after a strong run in the market and to sell after a sharp decline, I thought this temptation would be easier to resist if I knew exactly what I owned and why I owned it. Owning shares in a mutual fund meant trusting the fund manager to pick the right investments. Trust tends to erode after a period of losses.

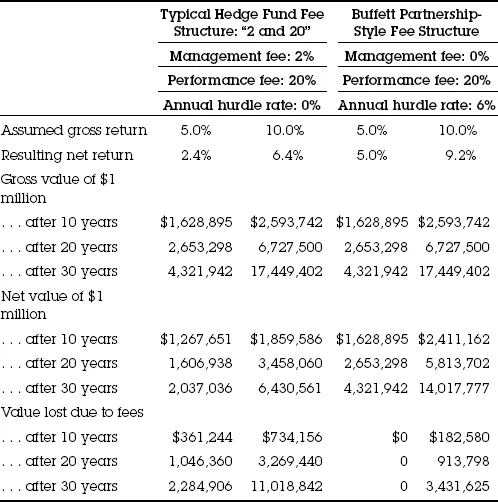

Mutual funds and lower-cost index funds should not be entirely dismissed, however, as they offer an acceptable alternative for those wishing to delegate investment decision making to someone else. Value mutual funds such as Bruce Berkowitz’s Fairholme Fund or Mason Hawkins’s Longleaf Funds are legitimate choices for many individual investors. High-net-worth investors and institutions enjoy the additional option of investing in hedge funds, but few of those funds deserve their typically steep management and performance fees. Warren Buffett critiqued the hedge fund fee structure in his 2006 letter to shareholders: “It’s a lopsided system whereby 2 percent of your principal is paid each year to the manager even if he accomplishes nothing—or, for that matter, loses you a bundle—and, additionally, 20 percent of your profit is paid to him if he succeeds, even if his success is due simply to a rising tide. For example, a manager who achieves a gross return of 10 percent in a year will keep 3.6 percentage points—two points off the top plus 20 percent of the residual eight points—leaving only 6.4 percentage points for his investors.”4

A small minority of value-oriented hedge fund managers have chosen to side with Buffett on the fee issue, offering investors a structure similar to that of the limited partnerships Buffett managed in the 1960s. Buffett charged no management fee and a performance fee only on returns in excess of an annual hurdle rate. The pioneers in this small but growing movement include Guy Spier of Zurich, Switzerland-based Aquamarine Capital Management and Mohnish Pabrai of Irvine, California-based Pabrai Investment Funds. These types of funds bestow a decisive advantage, ceteris paribus, on long-term investors. Table 1.1 shows the advantages of an investor-friendly fee structure.

TABLE 1.1 Effect of Fees on the Future Wealth of a Hedge Fund Investor

I also considered investing my savings in one of a handful of public companies that operate as low-cost yet high-quality investment vehicles. Berkshire Hathaway pays Warren Buffett an annual salary of $100,000 for arguably the finest capital allocation skills in the world. Buffett receives no bonus, no stock options, and no restricted stock, let alone hedge-fund-style performance fees.5 It certainly seems like investors considering an investment in a highly prized hedge fund should first convince themselves that their prospective fund manager can beat Buffett. Doing this on a pre-fee basis is hard enough; on an after-fee basis, the odds diminish considerably. Of course, buying a share of Berkshire is not quite associated with the same level of privilege and exclusivity as being accepted into a secretive hedge fund.

Berkshire is not the only public holding company with shareholder-friendly and astute management. Alternatives include Brookfield Asset Management, Fairfax Financial, Leucadia National, Loews Companies, Markel Corporation, and White Mountains Insurance. While these companies meet Buffett-style compensation criteria, some public investment vehicles have married hedge-fund-style compensation with a value investment approach. Examples include Greenlight Capital Re and Biglari Holdings. These hedge funds in disguise may ultimately deliver satisfactory performance to their common shareholders, but they are unlikely to exceed the long-term after-fee returns of a company like Markel, which marries superior investment management with low implied fees.

In light of the exceptional long-term investment results and low fees of companies like Berkshire and Markel, it may be irrational for any long-term investor to manage his or her own portfolio of stocks. Professional fund managers have a slight conflict of interest in this regard. Their livelihood depends rather directly on convincing their clients that the past performance of Berkshire or Markel is no indication of future results. Luckily for them, securities regulators play along with this notion, thereby doing their part in encouraging a constant flow of new entrants into the lucrative fund management business.

Rest assured, we won’t judge too harshly those who choose to manage their own equity investments. After all, that is precisely what I did with my savings in 2003 and have done ever since. You could say that underlying my decision has been remarkable folly, but here are a few justifications for the do-it-yourself approach: First, investment holding companies like Berkshire and Markel are generally not available for purchase at net asset value, implying that some recognition of skill is already reflected in their market price. While over time the returns to shareholders will converge with internally generated returns on capital, the gap is accentuated in the case of shorter holding periods or large initial premiums paid over net asset value. Even for a company like Berkshire, there is a market price at which an investment becomes no longer attractive.

In addition, one of the trappings of investment success is growth of assets under management. Few fund managers limit their assets, and this is even rarer among public vehicles. Buffett started investing less than $1 million six decades ago. Today he oversees a company with more than $200 billion in market value. If Buffett wanted to invest $2 billion, a mere 1 percent of Berkshire’s quoted value, into one company, he could not choose a company with a market value of $200 million. He would likely need to find a company quoted at $20 billion, unless he negotiated an acquisition of the entire business. Buffett is one of few large capital allocators who readily admit that size hurts performance. Many others evolve their view, perhaps not surprisingly, as their assets under management grow. Arguments include greater access to management, an ability to structure private deals, and the spreading of costs over a large asset base. Trust Buffett that these advantages pale in comparison with the disadvantage of a diminished set of available investments. If you manage $1 million or even $100 million, investing in companies that are too small for the superinvestors offers an opportunity for outperformance. Buffett agrees: “If I was running $1 million today, or $10 million for that matter, I’d be fully invested. Anyone who says that size does not hurt investment performance is selling. The highest rates of return I’ve ever achieved were in the 1950s. I killed the Dow. You ought to see the numbers. But I was investing peanuts then. It’s a huge structural advantage not to have a lot of money. I think I could make you 50% a year on $1 million. No, I know I could. I guarantee that.”6 The corollary: When small investors commit capital to mega-caps such as Exxon Mobil or Apple, they willingly surrender a key structural advantage: the ability to invest in small companies.

Echoing Buffett’s sentiments on the unique advantages of a small investable asset base, Eric Khrom, managing partner of Khrom Capital Management, describes the business rationale he articulated to his partners early on: “The fact that we are starting off so small will allow me to fish in very small pond where the big fishermen can’t go. So although I’m a one man shop, you don’t have to picture me competing with shops that are much larger than me, because they can’t look at the things I look at anyway. We will be looking at the much smaller micro caps, where there are a lot of inefficiencies. . . .”7

The last argument for choosing our own equity investments leads to the concept of capital allocation. Contrary to the increasingly popular view that the stock market is little more than a glorified casino, the market is supposed to foster the allocation of capital to productive uses in a capitalist economy. Businesses that add value to their customers while earning acceptable returns on invested capital should be able to raise capital for expansion, and businesses that earn insufficient returns on capital should fail to attract funding. A properly functioning market thereby assists the process of wealth creation, accelerating the growth in savings, investment, and GDP. If the role of the market is to allocate capital to productive uses, it becomes clear that a few dozen top investors cannot do the job by themselves. There are simply too many businesses to ...