![]()

Chapter 1

A True Sustainability Criterion and Its Implications

1.1 Introduction

Within the context of today’s technology development, the terms “sustainable” and “sustainability” refer to a concept that has become something of a buzzword on which different social, economic and political interests can (and do) hang some self-serving definitions. What these self-interested definitions have in common is their employment of terms to imply the acceptability of a process for some particular duration of time. True sustainability, on the other hand, cannot be a matter of such partial and subjective “definition”, including the endless debates and interpretations that come with such subjectivity. Highlighting the importance of using the concept of sustainability in every model of technology development. This chapter attempts to clarify what is involved in elaborating a scientific criterion for determining sustainability. Far from being an idle preoccupation which at first blush, might look like “wishful thinking,” the fundamental insight informing this particular exploration is that the economic arrangements needed for securing the benefits of such sustainability for all, can only be realized if the underlying science and its engineering in various technological forms are themselves sustainable.

As argued in Sustainable Energy Pricing (the earlier companion volume to the present book), the only true model of sustainability to be found lies in Nature, the natural environment. Both in its root-source and in the pathway taken by its development, a truly sustainable process conforms to connected, and/or underlying, natural phenomena. Scientifically, what could this mean? In this book, it means that true long-term considerations of humans should include the entire ecosystem. Some label this inclusion “humanization of the environment” and have deemed its inclusion to be a precondition of true sustainability (Zatzman and Islam, 2007). Of course: the inclusion of the entire ecosystem becomes meaningful only when the natural pathway for every component of the technology is followed. Only such a design may assure that the process will produce both short-term (tangible) and long-term (intangible) benefits.

However, tangibles relate to short-term (and very limited) space—more like ∂s (“the rate of change of displacement”) rather than plain old “pure and simple”s (displacement itself, as some fixed quantity). Intangible elements relate to either long-term elements or other elements of the current time-frame. Therefore, an exclusive or dominating focus on the tangible will obscure longer-term consequences from our collective awareness. Without including and properly analyzing intangible properties, of course, these consequences cannot be uncovered. According to Chhetri and Islam (2008), by taking the long-term approach, the outcome is reversed from the one that emerges from the shorter-term approach. As discussed infra in Chapter 2, by examining the efficiency (η) of different energy sources as delivered by various technologies, this distinction may be demonstrated almost graphically. By focusing on just heating value, for example, a ranking appears that diverges into what is observed today as the “global warming” phenomenon. On the other hand, if a long-term approach were taken, the current energy crunch would have been entirely avoided as none of the previously perpetrated technologies would have been considered “efficient” and replaced with truly, i.e., globally, efficient technologies. Such is the inherent importance of intangibles — and of how tangibles should link to them. Exploring many previously unremarked links between microscopic and macroscopic properties, this approach opens up a new understanding of the relationship between intangible-to-tangible scales.

It has long been accepted that Nature is self-sufficient and complete. This renders Nature the true teacher of how to develop sustainable technologies. From the standpoint of human intention, this self-sufficiency and completeness becomes a standard for declaring Nature perfect. “Perfect” here, however, does not mean that Nature is in one fixed unchanging state. On the contrary, it is the capacity of Nature to evolve and sustain itself which makes it such an excellent teacher. This perfection makes it possible and necessary for Humanity to learn from Nature — not to fix Nature, but to improve Humanity’s own condition and prospects within Nature, in all periods and for any timescale. This holds a subtle yet crucial significance for such emulation of Nature. The most notable consequence is that technological or other types of development undertaken within the natural environment but lacking consciousness of Nature’s “perfection,” must necessarily end up violating something fundamental within Nature, even if only for some limited time. Understanding the effect of intangibles and the relations of intangibles to tangibles thus becomes extremely important for reaching appropriate decisions affecting the welfare both of human societies and the natural environment. A number of aspects of natural phenomena are explored in this chapter with the aim of further bringing out the relationships between intangibles and tangibles and the connection of that relationship to true sustainability. This provides an especially strong basis for the sustainability model argued for in this book. The mass-and-energy-balance equation, for example, is discussed here with the aim of further illuminating the influence of the intangible and the role of intention.

1.2 Importance of a Sustainability Criterion

Few in our post-Renaissance world would disagree over whether we have made progress as a human race. Empowered with the New Science led by Galileo and later championed by Newton, modern engineering is credited with having universally revolutionized human lifestyle. Yet, centuries after those revolutionary contributions of the New Science pioneers, modern-day leading scientists such as Nobel Chemistry Laureate, Robert Curl find such technology development more akin to “technological disaster” rather than a source of marvels. Today’s engineering is driven by economic models that have been criticized trenchantly as inherently unsustainable by Nobel Laureates Joseph Stiglitz, Paul Krugman and Mohamed Yunus. This would seem to position much of the contemporary engineering art itself as environmentally unsustainable and socially unacceptable.

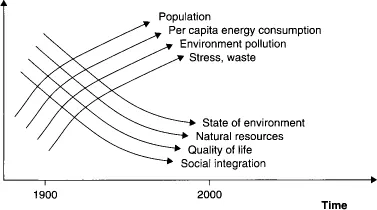

Figure 1.1 shows the nature of the problem currently facing human habitat as a result. Value indices that would imply improvement of human social status have declined. At the same time, per capita energy consumption has increased. This figure thus clearly signals a problem of direction in technology development. If increasing per capita energy consumption is synonymous with economic growth, — in line with modern-day notions of gross domestic product (GDP) — then further economic growth could only mean an even worse decline in the quality of the environment. What appears on its surface to be a very difficult but essentially technological problem, therefore, is also a fundamental problem of the outlook that has come to prevail in modern society’s evolution since the European Renaissance into the current-day Information Age.

Table 1.1 summarizes various man-made activities that have been synonymous with social progress and simultaneously responsible for much of the current global crisis. The current model is based on conforming to regulations and reacting to events. This response has remained purely reactive, ultimately rendering it ideologically and politically reactionary. Nowhere is any fundamentally proactive stance embraced or maintained with regard to environmental regulations among any of the developed countries. Conformity to regulations and rules that may themselves be utterly lacking any sustainable foundation can only increase long-term instability. This implies that conformity to law assures nothing in itself about sustainability — especially if those laws are based on something anti-nature.

Table 1.1 Energy consumed by various human activities.

| Activity | Btu | Calorie |

| Amatch | 1 | 252 |

| An apple | 400 | 100,800 |

| Making a cup of coffee | 500 | 126,000 |

| Stick of dynamite | 2,000 | 504,000 |

| Loaf of bread | 5,100 | 1,285,200 |

| Pound of wood | 6,000 | 1,512,000 |

| Running a TV for 100 hours | 28,000 | 7,056,000 |

| Gallon of gasoline | 125,000 | 31,500,000 |

| 20 days cooking on gas stove | 1,000,000 | 252,000,000 |

| Food for one person for a year | 3,500,000 | 882,000,000 |

| Apollo 17’s trip to the moon | 5,600,000,000 | 1,411,200,000,000 |

| Hiroshima atomic bomb | 80,000,000,000 | 20,160,000,000,000 |

| 1,000 transatlantic jet flights | 250,000,000,000 | 63,000,000,000,000 |

| United States in 1999 | 97,000,000,000,000,000 | 24,444,000,000,000,000,000 |

Environmental regulations and technology standards today widely enjoy unquestioning acceptance, to the extent that fundamental misconceptions embedded in them (and discussed below) are frequently left unquestioned. The fact that many of these regulations and standards follow no natural laws is frequently concealed behind complete nonsense, sometimes put forward as cracker-barrel common sense, such as “dilution is the solution to pollution.” No scientific-minded person could disagree that regulation that violates natural law has no chance of establishing a sustainable environment. With today’s regulations, for example, crude oil is considered to be toxic and therefore undesirable in a water stream. Of course, from the standpoint of human consumption, crude oil is more or less indigestible and hence undesirable… but toxic it is not. Meanwhile, according to the current regulatory regime developed in the U.S. by the EPA and followed in many other countries, the most toxic additives — frequently byproducts of refining crude oil — are not considered toxic.1

The slogan, “Dilution is the solution to pollution” has become a popular slogan in the environmental industry. All environmental regulations are based on this principle. The tangible aspect — viz., concentration — is considered, but the intangible aspect, such as the nature of the chemical, or its source, is not. Hence, ‘safe’ practices initiated on this basis are bound to become quite unsafe in the long run. Environmental impacts, however, are not a matter of minimizing waste or increasing remedial activities, but of humanizing the environment. This requires the elimination of toxic waste altogether. Even non-toxic waste should be recycled 100 percent. This involves not adding any anti-natural chemical to begin with, then making sure each produced material is recycled, with value-addition taking place wherever possible. A zero-waste process thus has 100 percent global efficiency attached to it. If a process emulates nature, such high efficiency is inevitable.

This process is the equivalent of “greening” petroleum technologies (Islam, 2011). With this mode, no one will attempt to clean water with toxic glycols, remove CO2 with toxic amides, or use toxic plastic paints as a “greening” process. No one will inject synthetic and expensive chemicals to increase “‘enhanced oil recovery’” (EOR). Instead, one would settle for waste materials or naturally available materials that are abundantly available and pose no threat to the eco-system.

The role of a scientific sustainability criterion is similar to that of the bifurcation point shown in Figure 1.2. This figure shows the importance of the first criterion. The solid circles represent natural (true) first premises, whereas the hollow circles represent aphenomenal (false) first premises. The thicker solid lines represent steps that would increase overall benefits to the whole system. At every phenomenal node, there will be spurious suggestions that would emerge from some aphenomenal roots (e.g. bad faith, bottom-line driven, myopic models), represented by dashed thick lines. However, if the first premise is sustainable, no node will appear ahead of the spurious suggestions. Every logical step will lead to sustainable options. The thinner solid lines represent choices that emerge from aphenomenal or false sust...