![]()

1

Introduction: Antibody Structure and Function

Arvind Rajpal, Pavel Strop, Yik Andy Yeung, Javier Chaparro-Riggers, and Jaume Pons

1.1 Introduction to Antibodies

Antibodies, a central part of humoral immunity, have increasingly become a dominant class of biotherapeutics in clinical development and are approved for use in patients. As with any successful endeavor, the history of monoclonal antibody therapeutics benefited from the pioneering work of many, such as Paul Ehrlich who in the late nineteenth century demonstrated that serum components had the ability to protect the host by “passive vaccination” [1], the seminal invention of monoclonal antibody generation using hybridoma technology by Kohler and Milstein [2], and the advent of recombinant technologies that sought to reduce the murine content in therapeutic antibodies [3].

During the process of generation of humoral immunity, the B-cell receptor (BCR) is formed by recombination between variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) exons, which define the antigen recognition element. This is combined with an immunoglobulin (Ig) constant domain element (μ for IgM, δ for IgD, γ for IgG (gamma immunoglobulin), α for IgA, and

for IgE) that defines the isotype of the molecule. Sequences for these V, D, J, and constant domain genes for disparate organisms can be found through the International ImMunoGeneTics Information System® [4]. The different Ig subtypes are presented at different points during B-cell maturation. For instance, all naïve B cells express IgM and IgD, with IgM being the first secreted molecule. As the B cells mature and undergo class switching, a majority of them secrete either IgG or IgA, which are the most abundant class of Ig in plasma.

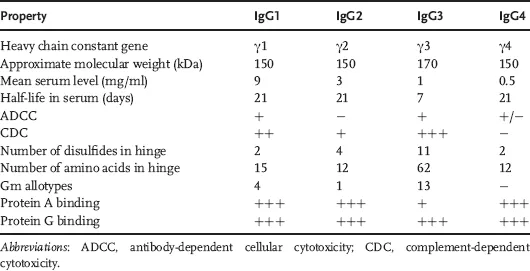

Characteristics like high neutralizing and recruitment of effector mechanisms, high affinity, and long resident half-life in plasma make the IgG isotype an ideal candidate for generation of therapeutic antibodies. Within the IgG isotype, there are four subtypes (IgG1–IgG4) with differing properties (Table 1.1). Most of the currently marketed IgGs are of the subtype IgG1 (Table 1.2).

Table 1.1 Subtype properties.

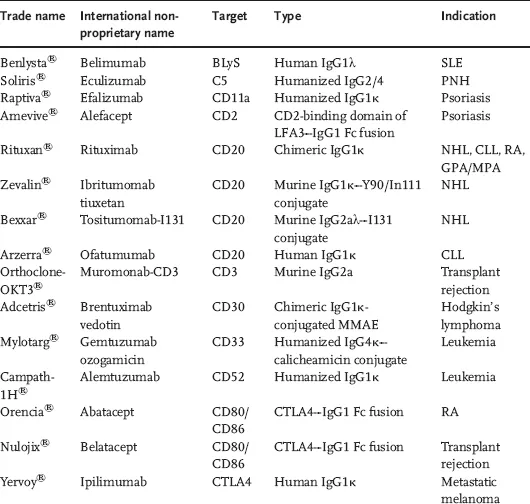

Table 1.2 Marketed antibodies and antibody derivatives by target.

The ability of antibodies to recognize their antigens with exquisite specificity and high affinity makes them an attractive class of molecules to bind extracellular targets and generate a desired pharmacological effect. Antibodies also benefit from their ability to harness an active salvage pathway, mediated by the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn), thereby enhancing their pharmacokinetic (PK) life span and mitigating the need for frequent dosing. The antibodies and antibody derivatives approved in the United States and the European Union (Table 1.2) span a wide range of therapeutic areas, including oncology, autoimmunity, ophthalmology, and transplant rejection. They also harness disparate modes of action like blockade of ligand binding and subsequent signaling, and receptor and signal activation, which target effector functions (antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC)), and delivery of cytotoxic payload.

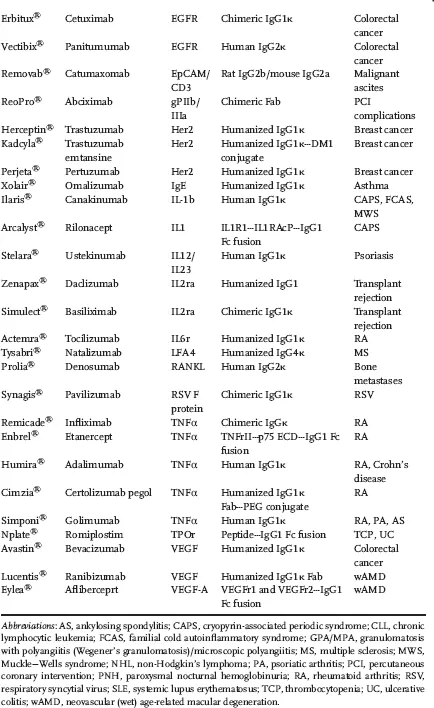

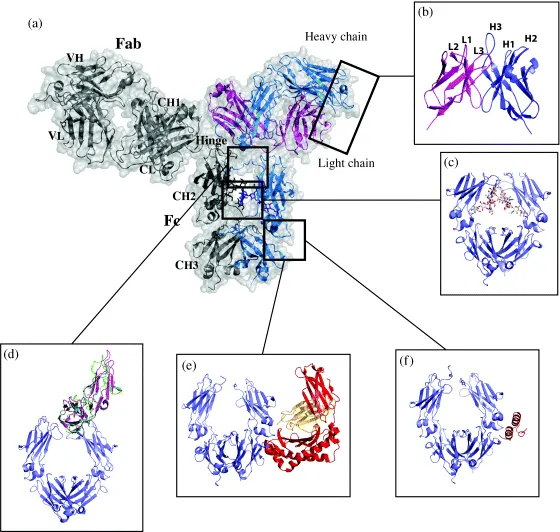

Antibodies are generated by the assembly of two heavy chains and two light chains to produce two antigen-binding sites and a single constant domain region (Figure 1.1, panel a). The constant domain sequence in the heavy chain designates the subtype (Table 1.1). The light chains can belong to two families (λ and κ), with most of the currently marketed antibodies belonging to the κ family.

The antigen-binding regions can be derived by proteolytic cleavage of the antibody to generate antigen-binding fragments (Fab) and the constant fragment (Fc, also known as the fragment of crystallization). The Fab comprises the variable regions (variable heavy (VH) [11] and variable light (VL)) and constant regions (CH1 and Cκ/Cλ). Within these variable regions reside loops called complementarity determining regions (CDRs) responsible for direct interaction with the antigen (Figure 1.1, panel b). Because of the significant variability in the number of amino acids in these CDRs, there are multiple numbering schemes for the variable domains [12,13] but only one widely used numbering scheme for the constant domain (including portions of the CH1, hinge, and the Fc) called the EU numbering system [14].

There are two general methods to generate antibodies in the laboratory. The first utilizes the traditional methodology employing immunization followed by recovery of functional clones either by hybridoma technology or, more recently, by recombinant cloning of variable domains from previously isolated B cells displaying and expressing the desired antigen-binding characteristics. There are several variations of these approaches. The first approach includes the immunization of transgenic animals expressing subsets of the human Ig repertoire (see review by Lonberg [15]) and isolation of rare B-cell clones from humans exposed to specific antigens of interest [16]. The second approach requires selecting from a large in vitro displayed repertoire either amplified from natural sources (i.e., human peripheral blood lymphocytes in Ref. [17]) or designed synthetically to reflect natural and/or desired properties in the binding sites of antibodies [18,19]. This approach requires the use of a genotype–phenotype linkage strategy, such as phage or yeast display, which allows for the recovery of genes for antibodies displaying appropriate binding characteristics for the antigen.

1.2 General Domain and Structure of IgG

Topologically, the IgG is composed of two heavy chains (50 kDa each) and two light chains (25 kDa each) with total molecular weight of approximately 150 kDa. Each heavy chain is composed of four domains: the variable domain (VH), CH1, CH2, and CH3. The light chain is composed of variable domain (VL) and constant domain (CL). All domains in the IgG are members of the Ig-like domain family and share a common Greek-key beta-sandwich structure with conserved intradomain disulfide bonds. The CLs contain seven strands with three in one sheet, and four in the other, while the VLs contain two more strands, resulting in two sheets of four and five strands.

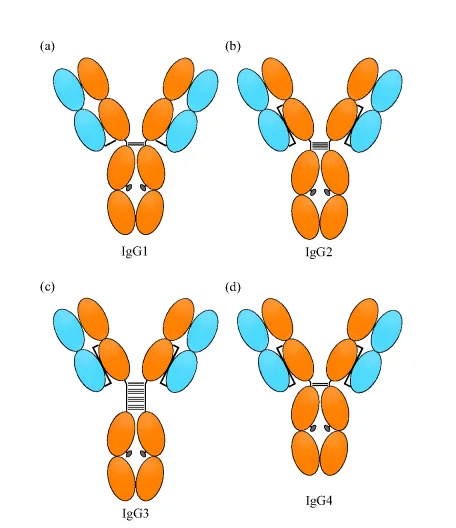

The light chain pairs up with the heavy chain VH and CH1 domains to form the Fab fragment, while the heavy chain CH2 and CH3 domains dimerize with additional heavy chain CH2 and CH3 domains to form the Fc region (Figure 1.1, panel c). The Fc domain is connected to the Fab domain via a flexible hinge region that contains several disulfide bridges that covalently link the two heavy chains together. The light chain and heavy chains are also connected by one disulfide bridge, but the connectivity differs among the IgG subclasses (Figure 1.2). The overall structure of IgG resembles a Y-shape, with the Fc region forming the base while the two Fab domains are available for binding to the antigen [6]. Studies have shown that in solution the Fab domains can adopt a variety of conformations with regard to the Fc region.

1.2.1 Structural Aspects Important for Fc Fusion(s)

1.2.1.1 Fc Protein–Protein Interactions

While the Fab region of an antibody is responsible for binding and specificity to a given target, the Fc region has many important functions outside its role as a structural scaffold. The Fc region is responsible for the long half-life of antibodies as well as for their effector functions including ADCC, CDC, and phagocytosis [20].

The long half-life of human IgGs relative to other serum proteins is a consequence of the pH-dependent interaction with the FcRn [21–23]. In the endosome, FcRn binds to the Fc region and recycles the antibody back to the plasma membrane, where the increase in pH releases the antibody back to the serum, thus rescuing it from degradation. The details of FcRn binding and its effects on antibody pharmacokinetics, including results from modulating FcRn interaction by protein engineering, are discussed in Section 1.3.3. One FcRn binds between the CH2 and CH3 domains of an Fc dimer half (Figure 1.1, panel e) [21]; therefore, up to two FcRns can bind to a single Fc.

Fc region is also responsible for binding to bacterial Protein A [10] and Protein G [24], which are commonly used for purification of Fc-containing proteins. Although Protein A binds to Fc mainly through hydrophobic interactions and Protein G through charged and polar interactions, Proteins A and G bind to a similar site on Fc domain and compete with each other (Figure 1.1, panel f). Interestingly, the binding occurs between the CH2 and CH3 domains of the Fc and largely overlaps with the FcRn binding site.

ADCC function is mediated by the interaction of the Fc region with Fcγ receptors (FcγRs). Biochemical data and structures of Fc in complex with FcγRIII and FcγRII reveal that the FcγRs bind to the combination of the Fc CH2 domain and the lower hinge region (Figure 1.1, panel d) [7,8,25]. Members of the Fcγ family have been found to bind to the same region of Fc [20,26,27] and form a 1 : 1 asy...