eBook - ePub

Eating the Big Fish

How Challenger Brands Can Compete Against Brand Leaders

Adam Morgan

This is a test

Buch teilen

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Eating the Big Fish

How Challenger Brands Can Compete Against Brand Leaders

Adam Morgan

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

EATING THE BIG FISH: How Challenger Brands Can Compete Against Brand Leaders, Second Edition, Revised and Expanded

The second edition of the international bestseller, now revised and updated for 2009, just in time for the business challenges ahead.

It contains over 25 new interviews and case histories, two completely new chapters, introduces a new typology of 12 different kinds of Challengers, has extensive updates of the main chapters, a range of new exercises, supplies weblinks to view interviews online and offers supplementary downloadable information.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Eating the Big Fish als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Eating the Big Fish von Adam Morgan im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Business & Advertising. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

PART 1

THE SIZE AND NATURE OF THE BIG FISH

1

THE LAW OF INCREASING RETURNS

At one level, we know all about the benefits for a Market Leader of critical mass—the advantages at consumer, company, and competitive levels the Brand Leader enjoys over every other player in the game due to their size advantage. And these are of course enviable advantages: Who would not want the distribution power of Anheuser-Busch over the trade, or the ubiquitous consumer visibility of Coca-Cola, or the research and development resources of Procter & Gamble?

But this is not the key point we are going to recognize here. Nor is the preference given to the social acceptability of the brand leader by the uncertain consumer (whatever Wilt Chamberlain thinks); nor indeed the formidable trust and reassurance it enjoys; nor yet the power of its monstrous marketing budget relative to ours. These are odds we know and understand. These all merely lead us as Challengers to talk generally about “trying harder” and “differentiating in our advertising,” and “focus.” Everything we are already trying at the moment.

What we are going to look at first is how, even knowing all this, we are still underestimating the difficulty of the situation facing us: The true dynamic is actually worse than this. For it is not just that Brand Leaders are bigger and enjoy proportionately greater benefits: The evidence we are going to consider suggests that the superiority of their advantage increases almost exponentially the larger they get.

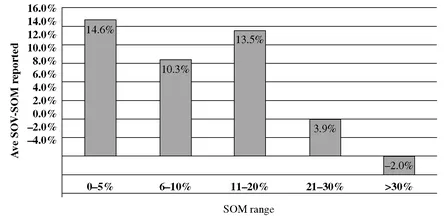

FIGURE 1.1 Small brands need greater excess SOV to grow.

Source: Les Binet and Peter Field, “Marketing in the Era of Accountability,” part of the IPA Datamine series.

THE LAW OF INCREASING RETURNS

The simplest illustration is that of the relationship between share of voice and share of market. We all know, from theory and experience, that there is a strong correlation between the two: that your share of market will usually correspond strongly with your share of voice, and if you want to increase your share of market you will have to increase your share of voice. John Philip Jones’s work has shown clearly that smaller brands need to spend proportionately more than larger brands simply to maintain equilibrium. Recent analysis confirms this to be true of growth as well: If one analyzes brands that have sought to grow, smaller brands have to disproportionately increase their share of spend ahead of share of market in order to grow, while larger brands, conversely, have to make relatively smaller increases in share of voice to derive those same market share increases.

This is illustrated in Figure 1.1. This graph examines the data of almost 900 growing brands where the growth was proven econometrically to come from the way they used communications. The horizontal axis on this graph groups the brands by their share of the market: the left-hand column, for instance, represents brands with 5 percent share of their market or lower, while the one on the far right represents brands with more than 30 percent market share. The vertical axis represents the percentage they have had to spend in share of voice ahead of their share of market to achieve that growth—the taller the bar, the more they have had to spend ahead of their share of market to achieve their growth. And what we see is that once you reach a certain size as a brand—20 percent—you start to have to spend proportionately much less to increase your share of market.

We can go on to see that this “law of increasing returns” plays out in a very similar way in four other key dimensions that are relevant to us. The easiest way to illustrate these differences is to map out the brand-consumer relationship into three stages (albeit rather crude ones) and look at the relative performances of the Brand Leader at each stage relative to a second- or lower-ranked brand in the same category. We then come on to look at the impact on profitability.

STAGE ONE: CONSUMER AWARENESS

First, awareness. Who does our target think about first?

Top-of-mind awareness, sometimes called salience, is the proportion of consumers for whom a certain brand comes to mind first when they are thinking about your category. An acknowledged key driver of purchase in lower-interest or impulse markets, like burgers and snacks, top-of-mind awareness is also an underestimated factor in shopping higher-interest categories. General spontaneous awareness, on the other hand (the proportion of people who are aware of your brand at all without prompting), is obviously important at some level to a brand’s success—people rarely buy an unfamiliar brand—but tends to reflect brand size and share of market: It often corresponds roughly to market share.

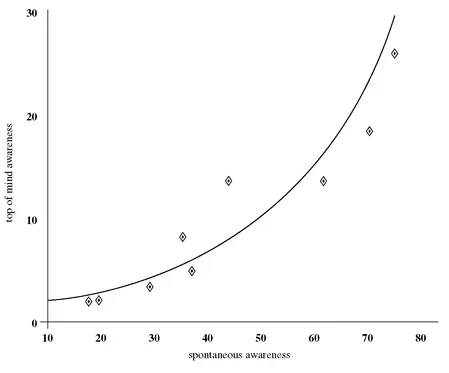

The assumption marketeers generally make is that the relationship between the two is a linear one—one’s total spontaneous awareness and top-of-mind awareness will rise in roughly equal proportions. Figure 1.2, however, taken from analysis of the relationship between the two among packaged goods brands in France by the advertising agency Lintas (now Lowe) in 1990, shows otherwise.1

What is striking here is that top-of-mind awareness increases quasi-exponentially in relation to total spontaneous awareness. That is to say, if I as Brand Leader am twice as big as the Number Two or Three, and spontaneous awareness is linked to market dominance, my top-of-mind awareness is on average close to four times as great. By the same token, if I as Brand Leader starting from a higher base increase either of these, my return will be almost exponentially greater, gain for gain, than that of a Challenger making the same gains lower down the scale.

FIGURE 1.2 Top-of-mind awareness versus total spontaneous awareness.

Source: U. van de Sandt/Lintas (now Lowe)

Not only, it seems, do Brand Leaders have more muscle and resources to start with, but it earns them almost twice as much top-of-mind awareness in return. Udo van de Sandt, the French strategic planner whose work this was, found the same relationship existed between “spontaneous brand awareness” and “usual/preferred brand.” We may have to differentiate more sharply than we thought.

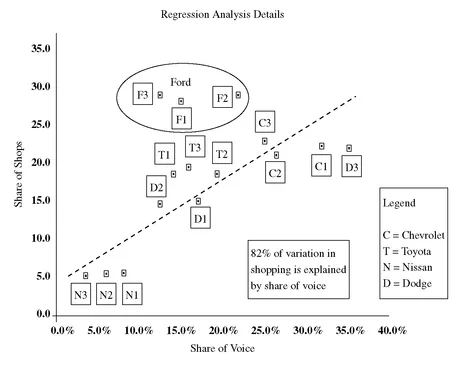

FIGURE 1.3 Hypershopping in the truck market.

Source: Cindy Scott/Allison Fisher

STAGE TWO: SHOPPING

What happens when the consumer leaves the house?

What happens is that this law of increasing returns is translated directly into shopping behavior. Imagine our consumer is shopping for a truck, for instance. Well, from a marketing point of view, you would expect that the more you advertised your new truck, the more footfall in-store you could generate compared to the competition. And this is true, up to a point. If one takes the U.S. compact pickup market, for instance, and plots the relationship between advertising spend and shopping across three consecutive years for each brand (Figure 1.3), there will be a close fit along a straight line for every brand—except the Ford Ranger. It alone did not obey the normal laws of proportionate returns.2

Why? Because the Ranger was the compact pickup segment leader and as such enjoyed a dramatically higher share of shopping, even when supported by a comparatively low share of voice. And we see all around us Market Leaders playing this card, knowing the strength of it for an important group of consumers, from Clarins talking in its advertising about its being “The European Leader in Luxury Skin Care” to a Singaporean bus side informing us that “Seoul Gardens is the world’s largest chain of Table Barbeque Restaurants.” If you are looking for a recommendation for somewhere to eat this evening, you can’t argue with that, it seems.

It looks as though, then, as an ambitious Number Two we will need to offer a greater source of differentiation, not just in our image, but in a way that genuinely impacts the entire shopping process. We cannot compete effectively with the brand leader under the existing rules.

STAGE THREE: PURCHASE AND LOYALTY

A picture is emerging. It translates even into purchase and loyalty, albeit in a less dramatic fashion.

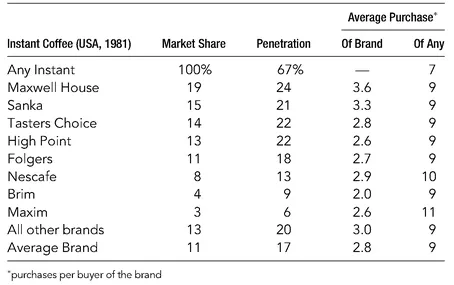

Double jeopardy is a brand phenomenon that has been studied and modeled by researchers in marketing for over 45 years across a variety of markets in cultures as diverse as the United States and Japan. It refers to the combined effects of two benefits that high-share brands profit from relative to low-share brands. The first of these benefits is the obvious one: High-share brands enjoy higher penetration (i.e., simply have more buyers) than low-share brands. The second, more interesting observation is that the buyers of high-share brands buy them more often than the buyers of low-share brands purchase those low-share brands (e.g., see Figure 1.4).

The cumulative effect of these two factors taken together leads to relative scale of increase in the number of purchases tending toward the exponential effect observed in the work on salience shown in Figure 1.2. (Some researchers, indeed, have claimed to observe variances for very high share brands greater even than this.)

FIGURE 1.4 Annual penetrations and average purchase frequencies (leading brands of U.S. instant coffee in their market-share order).

Source: MRCA/Professor A.S.C. Ehrenberg/R & DI3

THE CONSEQUENCE: PROFITABILITY

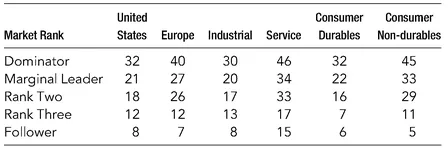

What, of course, all this leads up to is Brand Leaders making more damn money than we do. Figure 1.5 is taken from the Profit Impact of Market Strategy (PIMS) database; it shows the return on investment for a Brand Leader (split into two different kinds—dominators and marginal leaders) compared to second- and third-ranked brands.

FIGURE 1.5 Return on Investment % (average over four years).

Source: PIMS database of performance of 3,679 businesses, 2007, www.pimsconsulting.com

Look at the overall figure for the United States (the left-hand column): While a second-rank brand makes half as much profit again as a third-rank brand, a brand leader that dominates the category makes almost triple that. Or take durables: A second-rank brand makes twice as much as a Number Three, but a dominator doubles that again. I bring this up not just as a stockholder issue, but as a further compounding of the difference in resources between us. Those with an aversion to data tables may find the profitability of a market dominator illustrated a little more vividly by the remuneration of Roberto Goizueta, the late CEO of Coca-Cola, who became the first CEO to earn $1 billion in salary and bonuses alone. That has yet to happen at PepsiCo or Dr. Pepper.

If profit allows a company to make choices, to invest resources in finding sources of future competitive advantage, then this disparity serves to widen the discrepancy between the chips the Brand Leader has at its disposal and the pile we have to play with. As we have seen, each of a Brand Leader’s chips seems to win for it twice as much as ours.

Which is one of the reasons why so many Brand Leaders in fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) markets, for instance, are exactly the same brands that were Market Leaders 60 years ago.

So what?

The point of all this is not to suggest that it is difficult for second-rank brands to catch the Number One; as we will come to see, that is rarely their objective anyway. Nor is the point that at a crude level we as second-rank brands are outgunned more comprehensively than we thought (though we are). And we have not even come to talk about the kind of aggressive business practices pursued by Market Leaders to diminish the impetus, will, and opportunity for their lesser competitors.

What the law of increasing returns means is that we have to swim considerably more vigorously than the Brand Leader just to remain in the same place. Up to now, this has largely translated itself into conversations about relevance and focus: decisions about communication strategy and customer targeting.

But what if staying where we are in the future will not be enough? What if profitable survival in our category requires the achievement of rapid growth, in a probably static market, in the face of three new kinds of competition? Knowing that to follow the model of the Brand Leader is to help it increase its market advantage?

It would mean that we would need to abandon conservatism and incrementalism and start thinking like a Challenger just to survive healthily. It would mean we would have to behave and think about the way we marketed ourselves in a completely different kind of way. Find a different way of thinking about our goals and strategic objectives. Require, in fact, a different kind of decision-making process altogether.

A financial analyst was quoted approvingly in Financial World for commenting, “There is a certain trust associated with the McDonald’s brand name.” Continued the magazine, “Of course, [the analyst] has paid McDonald’s the ultimate compliment a service brand could hope to receive.”4

A service brand? Any service brand? A Brand Leader, maybe, but certainly not a Number Two or Three looking for growth. Of course trust is important—perhaps more important than ever before. But the currencies of quality, reassurance and trust, though they may well have been adequate until relatively recently for dominant Establishment brands, are woefully inadequate as the only basis for the kind of relationship we are going to need with our consumer. Facing...