![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introducing Geriatric Medicine

Nicola Cooper & Graham Mulley

OVERVIEW

- Developed countries have an ageing population

- Sick old people often present differently to younger people and can be clinically complex

- Atypical presentations such as reduced mobility are not ‘social’ problems – they are medical problems in disguise

- Comprehensive geriatric assessment and rehabilitation are of central importance to geriatric medicine and have a strong evidence base

- Simple interventions can often make a big difference to the quality of life of an older person

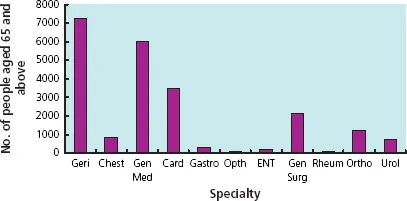

Geriatric medicine is important because most doctors deal with older patients. In the UK, people over the age of 65 make up around 16% of the population, but this group accounts for 43% of the entire National Health Service (NHS) budget and 71% of social care packages. Two-thirds of general hospital beds are used by older people and they present to most medical specialties (Figure 1.1).

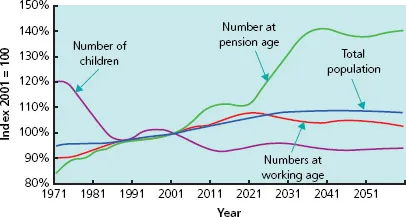

The proportion of older people is growing steadily (Figure 1.2), with even greater increases in the over 85 age group. According to official figures, the numbers of people aged 85 and over are projected to grow from 1.1 million in 2000 to 4 million in 2051.

Geriatric medicine is mainly concerned with people over the age of 75, although most ‘geriatric’ patients are much older. Many of these have several complex, interacting medical and psychosocial problems which affect their function and independence.

Age-related differences

There are important differences in the physiology and presentation of older people that every clinician needs to know about. These in turn affect assessment, investigations and management (Box 1.1).

Special features of illness in older people include the following.

Multiple pathology

Older people commonly present with more than one problem, usually with a number of causes. A young person with fever, anaemia, a heart murmur and microscopic haematuria may have endocarditis, but in an older person this presentation is more likely to be due to a urinary tract infection, aspirin-induced gastritis and aortic sclerosis. Never stop at a single unifying diagnosis – always consider several.

Figure 1.1 The numbers of people aged 65 and above admitted to a general hospital each year, by specialty. (Figures from the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust.) Geri, geriatric medicine; Chest, chest medicine; Gen Med, general medicine; Card, cardiology; Gastro, gastroenterology; Opth, ophthalmology; ENT, ear, nose and throat; Gen Surg, general surgery; Rheum, rheumatology; Ortho, orthopaedics; Urol, urology.

Figure 1.2 Changes in the proportion of people aged 65 and above among the overall population. Information from The UK National Census (2001).

Atypical presentation

Older people commonly present with ‘general deterioration’ or functional decline. Acute disease is often masked but precipitates functional impairment in other areas. Therefore atypical presentations such as falls, confusion or reduced mobility are not social problems – they are medical problems in disguise (Box 1.2). Often the history has to be sought from relatives and carers, over the telephone if necessary.

Box 1.1 Atypical presentation

An 85-year-old lady was recovering from surgery on an orthopaedic ward when she became withdrawn and stopped eating and drinking. Before this she had been well and mobilising. Her temperature, pulse, blood pressure and ‘routine bloods’ were normal. Her carers thought she was acting as if she wanted to die. However, it was later noted that her respiratory rate was high and a subsequent chest X-ray showed pneumonia. The patient was treated with antibiotics and recovered.

Box 1.2 Joint statement from the Royal College of Physicians and British Geriatrics Society on Intermediate Care, 2001

‘At the core of geriatric medicine as a specialty is the recognition that older people with serious medical problems do not present in a textbook fashion, but with falls, confusion, immobility, incontinence, yet are perceived as a failure to cope or in need of social care. This misconception that an older person’s health needs are social leads to a prosthetic approach, replacing those tasks they cannot do themselves rather than making a medical diagnosis. Thus the opportunity for treatment and rehabilitation is lost, a major criticism of some current services for older people. Old age medicine is complex and a failure to attempt to assess people’s problems as medical are unacceptable...Deficiencies in medical care can lead to failure to make a diagnosis; improper and inadequate treatment; poor clinical outcomes; inappropriate or wasteful use of scarce resources; communication errors and possible neglect.’

Reduced homeostatic reserve

Ageing is associated with a decline in organ function with a reduced ability to compensate. The ability to increase heart rate and cardiac output in critical illness is reduced; renal failure due to medications or illness is more likely; salt and water homeostasis is impaired so electrolyte imbalances are common in sick older people; thermoregulation may also be impaired. In addition, quiescent diseases are often exacerbated by acute illness; for example heart failure may occur with pneumonia and old neurological signs may become more pronounced with sepsis.

Impaired immunity

Older people do not necessarily have a raised white cell count or a fever with infection. Hypothermia may occur instead. A rigid abdomen is uncommon in older people with peritonitis – they are more likely to get a generally tender but soft abdomen. Measuring the serum C-reactive protein can be useful when screening for infection in an older person who is non-specifically unwell.

Some clinical findings are not necessarily pathological

Neck stiffness, a positive urine dipstick in women, mild crackles at the bases of the lungs, a slightly reduced PaO2 and reduced skin turgor may be normal findings in older people and do not always indicate disease.

The importance of functional assessment and rehabilitation

Older people may take longer to recover from illness (e.g. pneumonia) compared with younger people. However, their ability to perform activities of daily living and thus gain independence can improve dramatically if they are given time and rehabilitation.

Ethics

Geriatric medicine involves balancing the right to high-quality care without age discrimination with the wisdom to avoid aggressive and ultimately futile interventions. End-of-life decisions, risks vs benefits, capacity and consent, and dealing with vulnerable adults are all part of geriatric medicine.

In acute illness, the above factors combined can make clinical assessment very difficult and early intervention more important. For example, in severe sepsis, older patients may have cool peripheries and appear ‘shut down’, with a normal white cell count and no fever. Drowsiness is common, and does not necessarily indicate a primary brain problem. The patient may not be able to give a history, and their usual level of function and previously expressed wishes may not be known. Thus, gathering as much information as possible, as soon as possible, is vital.

Comprehensive geriatric assessment

In the 1930s, the very first geriatricians realised that the thousands of patients living in hospitals and workhouses were not suffering from ‘old age’ but from diseases that could be treated: immobility, falls, incontinence and confusion – called the ‘geriatric giants’ because they are the common presentations of different illnesses in older people (Box 1.3).

Today, geriatric medicine is the second biggest hospital specialty in the UK and a popular career choice. It involves dealing with acute illness, chronic disease and rehabilitation, working in multidisciplinary teams in the community and in hospitals, medical education and research.

Comprehensive geriatric assessment is the assessment of a patient made by a team which includes a geriatrician, followed by interventions and goal setting agreed with the patient and carers. This can take place in the community, in assessment areas linked to the emergency department, or in hospital. It covers the following areas:

- medical diagnoses

- review of medicines and concordance with drug therapy

- social circumstances

- assessment of cognitive function and mood

- functional abilit...