![]()

MODULE II

Governance Structures in Private Equity

![]()

CHAPTER 6

The Private Equity Governance Model

Harry Cendrowski

Adam A. Wadecki

INTRODUCTION

Private equity (PE) firms possess unique governance structures that permit them to be active investors in the truest sense of the term. Through large equity stakes, management interests in PE portfolio companies become aligned with those of all shareholders, and a sense of ambition is instilled in the executives managing these firms.

This chapter explores the PE governance model and the significant differences between it and the governance structures of public corporations. Implications for “public company” PE firms are also discussed.

A NEW MODEL FOR CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

In 1989, noted Harvard Business School Professor Michael C. Jensen wrote, “The publicly held corporation, the main engine of economic progress in the United States for a century, has outlived its usefulness in many sectors of the economy and is being eclipsed.” Jensen appropriately titled his article in the Harvard Business Review, “Eclipse of the Public Corporation.” Central to Jensen’s article was the notion that PE firms, “organizations that are corporate in form but have no public shareholders,” were emerging in place of public corporations.1

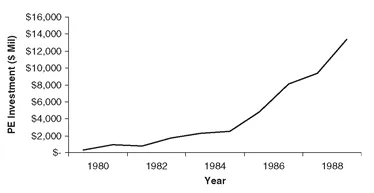

EXHIBIT 6.1 Historical Inflation-Adjusted Private Equity Investment Levels

Source: Thomson’s VentureXpert database.

In the late 1980s, the PE market was burgeoning. With the U.S. Department of Labor’s clarifications to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) in 1979 came significant inflows to alternative asset classes. As shown in Exhibit 6.1, PE investment levels in portfolio companies grew from an inflation-adjusted $348 million in 1980 to $13.4 billion in 1989; this represents a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of over 300 percent per year.

Buyouts gained in popularity throughout the 1980s as interest rates, now available at half the rates of the early 1980s, decreased significantly and the number of distressed corporations grew. With some equity investors earning as much as 60 percent to 100 percent per year on their investments, the buyout binge was borne.2 Managers overseeing portfolios at institutional investment firms began allocating large portions of their portfolio to PE in an attempt to both diversify their investments and achieve higher rates of return than what was available in public markets.

Entire industries were restructured during this time period, including the automotive supply, rubber tire, and casting industries, among others. The tire industry during this time was characterized by the CEO of Uniroyal Goodrich as a “dog-eat-dog business.”3 Those companies that survived these difficult times moved swiftly to counteract the fierce headwinds caused by intense competition; others that failed to perceive these fundamental changes in their external environment experienced significant hardships.

With the growth in PE investments came increased scrutiny from the public—especially for buyout funds—and a general distaste for the tactics employed by leveraged buyout (LBO) shops. A 1989 article in the

Wall Street Journal expressed investors’ growing antipathy for the structure of such transactions:

Leveraged buyouts are routinely criticized for being the product of financial engineers with sharp pencils but little appreciation for running and improving enterprises. There’s little doubt that a number of transactions have been completed at exceptionally high purchase prices by investor groups just hoping to divest divisions at even higher prices. Worse still, some LBOs are so highly leveraged that investment funds for crucially important product, market, and manufacturing improvements are simply unavailable; the burden of debt service takes priority.4

During the buyout craze of the 1980s, many saw buyout shops as a new kind of “evil empire,” mercilessly slashing costs at portfolio firms in order to increase exit multiples, and hence, a business’s valuation. It was during the late 1980s that some of the buyout’s largest magnates, like T. Boone Pickens and Carl Icahn, earned their reputation for purchasing distressed firms, laying off employees, cutting research and development (R&D) budgets, and subsequently selling off parts of the company to the highest bidder. Other public-company figures like “Chainsaw Al” Dunlap only helped to fuel both Wall Street’s and American consumers’ distaste for such operational methods.

Working as a CEO at Lily Tulip Corporation, Dunlap “fired most of the senior managers, sold the corporate jet, closed the headquarters and two factories, dumped half the headquarters staff, and laid off a bunch of other workers. The stock price rose from $1.77 to $18.55 in his two-and-a-half-year tenure.” Subsequently, while at Scott Paper, Dunlap “fired 11,000 employees (including half the managers and 20 percent of the company’s hourly workers), eliminated the corporation’s $3-million philanthropy budget, slashed R&D spending, and closed factories. Scott’s market value stood at about $3 billion when Dunlap arrived in mid-1994. In late 1995, he sold Scott to Kimberly-Clark for $9.4 billion, pocketing $100 million for himself ...”5 However, despite a general disinclination toward such methods, defenders of the buyout boom aptly pointed out that many firms purchased by buyout funds may have gone out of business if it were not for their sometimes cutthroat practices.

Until the past decade, PE funds generally focused on targeting either growing firms or declining businesses participating in mature industries: The former was the focus of venture capitalists, while the latter was the focus of buyout funds. In recent years, however, buyout funds have moved away from purchasing strictly asset-intensive businesses (e.g., manufacturing), seeking out companies in once high-growth sectors (e.g., computer hardware, such as the LBO of Seagate Corporation).

To clarify, a leveraged buyout is a transaction in which a private investment group acquires a company by employing a large amount of debt. Companies that have been acquired through an LBO typically have a debt-to-equity ratio of roughly 2-to-1, although this ratio was as high as 9-to-1 for some transactions in the late 1980s.

When acquiring a target firm, LBO funds generally look for targets with strong free cash flow and low volatility of these cash flows; when the business produces a significant amount of cash, debt payments can easily be made. Low levels of capital expenditures, a lower debt-to-equity ratio (i.e., conservative capital structure), and market leadership or former market leadership are all traits that LBO funds look for when screening potential companies.

By contrast, a venture capital (VC) deal is a transaction in which a private investment group provides capital to a growing firm primarily through the use of equity. Because many venture-backed firms lack “hard assets,” banks are often unwilling to lend debt at reasonable interest rates. Moreover, the asset volatility and uncertainty associated with venture-backed portfolio companies does not lend itself well to debt service, where cash stability is a requirement for making periodic interest payments.

Management buyouts, LBOs, hostile takeovers, and corporate breakups—the magnitude of which had never before been seen—have now became commonplace. And many of these deals have successfully transformed the companies they sought to change. Why, then, were so many of these deals successful at transforming declining organizations when previous management faltered? According to Jensen, management in public corporations is controlled by three forces: the product markets, internal control systems, and the capital markets.6 Of these forces, Jensen argued that only the capital markets have truly imposed discipline on managers, although the product markets have become a strong force for change since Jensen first wrote his article.

For years, the U.S. markets were immune to foreign competition: oligopolistic competition among firms permitted the realization of large economies of scale, and product markets had not yet matured to the point of permitting the global exchange on a massive scale. As these markets developed, many companies failed to react to overseas competition, primarily because these firms believed that the competition was ephemeral and the products were subpar. Consumers, however, soon found that foreign producers offered products of comparable (and sometimes better) quality for a cheaper price. Old-line domestic producers simply couldn’t compete against new, nimble entrants to the U.S. marketplace.

In this manner, many domestic firms failed to recognize and properly evaluate the strength of their new competitors—and their products—and did not react to changes in their external environment. It is thus clear that the internal control systems at such corporations were woefully inadequate at instituting a corporate culture committed to properly perceiving changes in its environment and reacting to them in a prompt manner.

An Analogy to Physics

In physics, force is the product of mass and acceleration; an increase in either quantity leads to a commensurate increase in the force. Equation 1 presents Sir Isaac Newton’s Second Law of Motion, which asserts that force (F) equals mass (m) multiplied by acceleration (a).

(1)

The critical examination of corporations can likewise be applied to this fundamental quantity so well studied by novice scientists. Let us first examine the concept of mass as applied to an organization.

Organizational mass can be defined by numerous factors: the amount of time a firm has been in business; the size of the company’s revenues, earnings, interest payments, and the like; the number of people it employs; its market share; and its market leadership position, among other things. It is important to note that, unlike weight for individuals, organizational mass need not carry negative connotations. Much like the blue whale in the ocean, organizational mass can be a symbol of pride for the company and its employees—but it can also be a detriment.

Company managers continually work hard to expand the firm’s revenues and grow market share and earnings in an attempt to increase shareholder value. While the achievement of such growth is tantamount to the success of the firm itself, it also creates organizational mass as these accomplishments are realized.

Returning, then, to

equation 1, we rearrange to obtain

equation 2:

(2)

Here, note that acceleration is equivalent to force over mass. For organizations, this simple relationship carries large implications: In order to “accelerate” the company toward the achievement of a new goal, larger forces must be applied as organizational mass is increased. In other words, the more “mass” a company carries, the harder its management team must push in order to change the status quo. The greater the acceleration a management team can induce, the faster the company will move toward its goal.

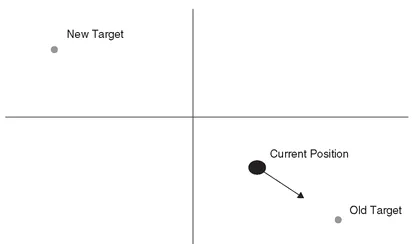

Extending the analogy a bit further, let us assume that we have the scenario presented in Exhibit 6.2.

In this scenario, a firm is currently moving toward a previously established target. However, management has determined —perhaps due to product markets, capital markets, or a firm’s internal control system—that the firm must move to a new target as soon as possible. Achieving this goal requires the firm to reverse entirely its current moving course and accelerate toward the new target.

EXHIBIT 6.2 Relationship between New and Old Corporate Targets

For nimble firms of relatively small orga...