![]()

Part 1: Growth and Development

1

An introduction to human craniofacial growth and development

‘Growth’ is a general term implying simply that something changes in magnitude. It does not, however, presume to account for how it happens. For the clinician, such a loose meaning is often used quite properly. However, to try to understand ‘how’ it works, and what actually happens, the more descriptive and explanatory term ‘development’ is added. This connotes a maturational process involving progressive differentiation at the cellular and tissue levels, thereby focusing on the actual biological mechanism that accounts for growth.

‘Growth and development’ is an essential topic in many clinical disciplines and specialties, and the reason is important. Morphogenesis is a biological process having an underlying control system at the cellular and tissue levels. The clinician intervenes in the course of this control process at some appropriate stage and substitutes (augments, overpowers or replaces) some activities of the control mechanism with calculated clinical regulation. It is important to understand that the actual biological process of development itself is the same. That is, the histogenic functioning of the cells and tissues still carry out their individual roles, but the control signals that selectively activate the composite of them are now clinically manipulated. It is the rate, timing, direction and magnitude of cellular divisions, and tissue differentiation that become altered when the clinician’s signals modify or complement the body’s own intrinsic growth signals. The subsequent course of development thus proceeds according to a programmed treatment plan by ‘working with growth’ (an old clinical tenet). Of course, if one does not understand the workings of the underlying biology, any real grasp of the actual basis for treatment design and results, and why, is an illusion. Importantly, craniofacial biology is independent of treatment intervention strategy. Therefore, although some clinicians may argue about the relative merits of different intervention strategies (e.g. extraction versus arch expansion), the biological rules of the game are the same.

Morphogenesis works constantly towards a state of composite, architectonic balance among all of the separate growing parts. This means that the various parts developmentally merge into a functional whole, with each part complementing the others as they all grow and function together.

During development, balance is continuously transient and can never actually be achieved because growth itself constantly creates ongoing, normal regional imbalances. This requires other parts to constantly adapt (develop) as they all work toward composite equilibrium. It is such an imbalance itself that fires the signals which activate the interplay of histogenic responses. Balance, when achieved for a time, turns off the signals and regional growth activity ceases. The process recycles throughout childhood, into and through adulthood (with changing magnitude) and finally on to old age, sustaining a changing morphological equilibrium in response to ever-changing intrinsic and external conditions. For example, as a muscle continues to develop in mass and function, it will outpace the bone into which it inserts, both in size and in mechanical capacity. However, this imbalance signals the osteogenic, chondrogenic, neurogenic and fibrogenic tissues to immediately respond, and the whole bone with its connective tissues, vascular supply and innervation develops (undergoes modelling) to work continuously towards homeostasis.

By an understanding of how this process of progressive morphogenic and histogenic differentiation operates, the clinical specialist thus selectively augments the body’s own intrinsic activating signals using controlled procedures to jump-start the modelling process in a way that achieves an intended treatment result. For example, in patients with maxillary transverse deficiency, rapid palatal expansion can be used to separate the right and left halves of the maxilla (displacement). This in turn initiates a period of increased remodelling activity in the midpalatal suture and dentoalveolus.

The genetic and functional determinants of a bone’s development (i.e. the origin of the growth-regulating signals) reside in the composite of soft tissues that turn on or turn off, or speed up or slow down, the histogenic actions of the osteogenic connective tissues (periosteum, endosteum, sutures, periodontal ligament). Growth is not ‘programmed’ within the bone itself or its enclosing membranes. The ‘blueprint’ for the design, construction and growth of a bone thus lies in the muscles, tongue, lips, cheeks, integument, mucosae, connective tissues, nerves, blood vessels, airway, pharynx, the brain as an organ mass, tonsils, adenoids and so forth, all of which provide information signals that pace the histogenic tissues responsible for a bone’s development.

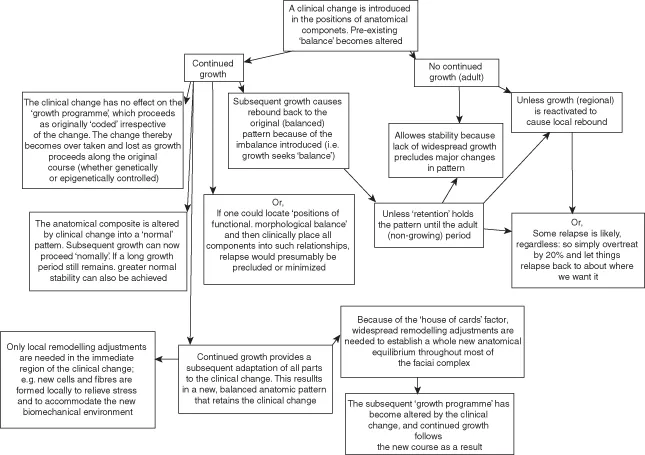

A major problem with therapeutic modification of the growing face can be relapse (rebound subsequent to treatment). The potential for relapse exists when the functional, developmental or biomechanical aspects of growth among key parts are clinically altered to a physiologically imbalanced state. The possibility of instability exists because clinicians strive to bring about a state of aesthetic balance that at times produces physiological imbalance. Rebound is especially strong when the underlying conditions in the ‘genic’ tissues that led to the pretreatment dysplasia still exist and thus trigger the growth process to rebound in response to the clinically induced changes in morphology. The ‘genic’ tissues are attempting to restore physiological balance, thereby returning in a developmental direction towards the pretreatment state or some combination between. Physiological compensation is, in effect, a built-in protective mechanism that allows the final occlusion of the teeth to vary only a mere few millimetres, despite enormous variation in the human face (see Figure 1.1).

The evolutionary design of the human head is such that certain regional clinical situations naturally exist. For example, variations in headform design establish natural tendencies toward different kinds of malocclusions. The growth process, in response, develops some regional imbalances, the aggregate of which serves to make corrective adjustments. A Class I molar relationship with an aesthetically pleasing face is the common result in which the underlying factors that would otherwise have led to a more severe Class II or III malocclusion still exist but have been ‘compensated for’ by the growth process itself. The net effect is an overall, composite balance.

As pointed out above, clinical treatment can disturb a state of structural and functional equilibrium, and a natural rebound can follow. For example, a premature fusion of some cranial sutures can result in growth-retarded development of the nasomaxillary complex because the anterior endocranial fossae (a template for midfacial development) are foreshortened, as in the Crouzon or Apert syndrome. The altered nasomaxillary complex itself nonetheless has grown in a balanced state proportionate to its basicranial template, even though abnormal in comparison with a population norm for aesthetics and function. Craniofacial surgery disturbs the former balance and some degree of natural rebound can be expected. The growth process attempts to restore the original state of equilibrium, since some extent of the original underlying conditions (e.g. the basicranium) can still exist that was not, or could not be, altered clinically. These are examples in which the biology of the growth process is essentially normal, either with treatment or without, but is producing abnormal results because of altered input control signals.

THE BIG PICTURE

No craniofacial component is developmentally self-contained and self-regulated. Growth of a component is not an isolated event unrelated to other parts. Growth is the composite change of all components. For example, it might be perceived that the developing palate is essentially responsible for its own intrinsic growth and anatomical positioning, and that an infant’s palate is the same palate in the adult simply grown larger. The palate in later childhood, however, is not composed of the same tissue (with more simply added), and it does not occupy the same actual position. Many factors influence (impact) the growing palate from without, such as developmental rotations, displacements in conjunction with growth at sutures far removed, and multiple remodelling movements that relocate it to progressively new positions and adjust its size, shape and alignment continuously throughout the growth period.

Similarly, for the mandible, the multiple factors of middle cranial fossa expansion, anterior cranial fossa rotations, tooth eruption, pharyngeal growth, bilateral asymmetries, enlarging tongue, lips and cheeks, changing muscle actions, headform variations, an enlarging nasal airway, changing infant and childhood swallowing patterns, adenoids, head position associated with sleeping habits, body stance and an infinite spread of morphological and functional variations all have input in creating constantly changing states of structural balance.

As emphasised above, development is an architectonic process leading to an aggregate state of structural and functional equilibrium, with or without an imposed malocclusion or other morphologic dysplasia. Very little, if anything, can be exempted from the ‘big picture’ of factors affecting the operation of the growth control process and no region can be isolated. Meaningful insight into all of this underlies the basis for clinical diagnosis and treatment planning. Ideally, the target for clinical intervention should be the control process regulating the growth and development of the component out of balance. However, gaps in our understanding of these processes limit the clinician’s ability to treat malocclusions in this manner. Since cause is unknown, clinicians target the effect of the imbalance. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the process and pattern of facial growth serves as the foundation for craniofacial therapies.

A CORNERSTONE OF THE GROWTH PROCESS

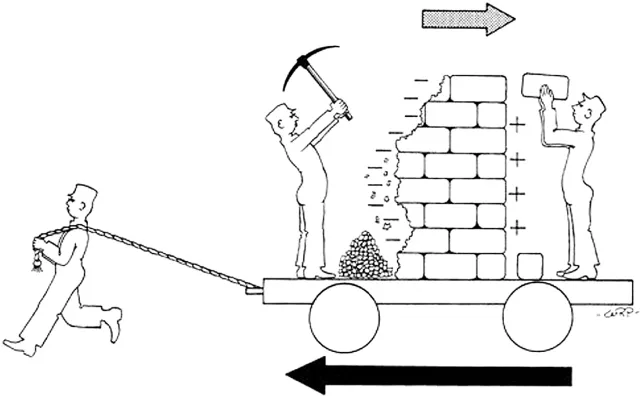

A grasp of how facial growth operates begins with distinguishing between the two basic kinds of growth movement: remodelling and displacement (Figure 1.2). Each category of movement involves virtually all developing hard and soft tissues.

For the bony craniofacial complex, the process of growth remodelling is paced by the composite of soft tissues relating to each of the bones. The functions of remodelling are to: (1) progressively create the changing size of each whole bone; (2) sequentially relocate each of the component regions of the whole bone to allow for overall enlargement; (3) progressively shape the bone to accommodate its various functions; (4) provide progressive fine-tune fitting of all the separate bones to each other and to their contiguous, growing, functioning ...