![]() PART 1

PART 1

Oesophagus![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Normal Oesophagus: Anatomy, Specimen Dissection and Histology Relevant to Pathological Practice

Kaiyo Takubo1 and Neil A. Shepherd2

1Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology and Tokyo Medical and Dental University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

2Gloucestershire Cellular Pathology Laboratory, Cheltenham, UK

Anatomy

The adult oesophagus is a muscular tube some 250 mm long, which extends from the pharynx, at the cricoid cartilage opposite the sixth cervical vertebra, to the oesophago-gastric junction, about 25 mm to the left of the midline, opposite the tenth or eleventh thoracic vertebra. The oesophagus has longitudinal mucosal folds and, when empty, a very narrow lumen. For endoscopists, the distance from the incisor teeth to the upper end of the oesophagus is about 150 mm and to the oesophago-gastric junction about 400 mm, depending, clearly, on the height of the person. The oesophagus pierces the left crus of the diaphragm and has an intra-abdominal portion about 15 mm in length. Its principal relations, important to the pathologist in assessing the local spread of cancer, are with the trachea, left main bronchus, aortic arch, descending aorta and left atrium.

The arterial supply of the oesophagus is by the inferior thyroid, bronchial, left phrenic and left gastric arteries and by small branches directly from the aorta. Its veins form a well-developed submucosal plexus draining into the thyroid, azygos, hemiazygos and left gastric veins. It, thus, provides an important link between the systemic and portal venous systems. Lymphatic channels from the pharynx and upper third of the oesophagus drain to the deep cervical lymph nodes, either directly or through the paratracheal nodes, and also to the infrahyoid lymph nodes; from the lower two-thirds they drain to the posterior mediastinal (para-oesophageal) lymph nodes and thence to the thoracic duct. From the infra-diaphragmatic portion of the oesophagus, drainage is to the left gastric lymph nodes and to a ring of lymph nodes around the cardia. Some lymph vessels may drain directly into the thoracic duct. In its upper part the oesophagus is innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve and, throughout its length, it is supplied by fibres from the vagus nerve and local sympathetic ganglia.

The lower end of the oesophagus is anchored posteriorly to the pre-aortic fascia and is surrounded by the phreno-oesophageal ligament, which blends into the muscularis propria of the oesophagus. This arrangement allows some degree of movement and rebound. Dissection studies indicate that no discrete anatomical sphincter is present but there are differences of opinion as to whether, and if so how, the muscle at the oesophago-gastric junction is modified. One careful anatomical study [1] has ruled out the presence of any thickening of the muscularis mucosae or of the circular muscle coat but has described the separation of obliquely arranged inner circular muscle fibres into fascicles, which continue into the stomach to form the circular muscle layer. However, another equally thorough investigation [2] describes a definite thickening of the inner circular muscle coat. Both studies have concluded that the arrangements that they describe might, and probably do, act as a functional sphincter.

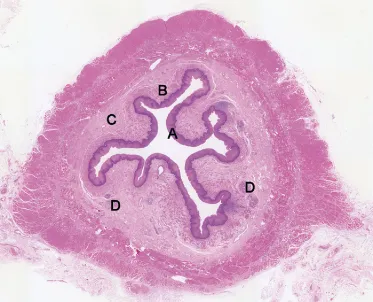

The oesophageal wall in cross-section can be divided macroscopically into stratified squamous epithelium, lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, and the submucosa, muscularis propria and adventitia (Figure 1.1). Gross inspection of cut sections of tumours in the oesophagus generally reveals the depth of tumour invasion and this assessment of depth, through the various layers of the wall, is of critical importance for staging and prognostication.

Histology

Mucosa

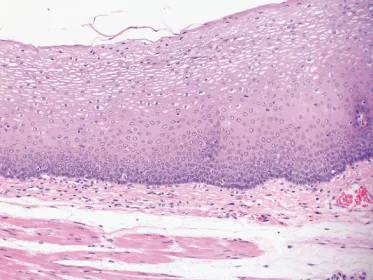

The squamous-lined mucosa is about 500–800 µm thick and is composed of non-keratinising stratified squamous epithelium with a subjacent lamina propria resting on the underlying muscularis mucosae.

Epithelium

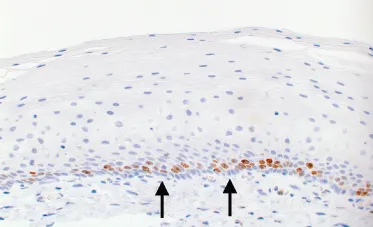

Resection specimens usually have a thinner squamous epithelium compared with biopsy specimens because the superficial layers are likely to be lost during surgical handling. The squamous epithelium (Figure 1.2) has a basal zone consisting of several layers of cuboidal or rectangular basophilic cells, with dark nuclei, in which glycogen is absent. It occupies about 10–15% of the thickness of the normal epithelium, although it may be thicker in the last 20 mm or so of the squamous-lined oesophagus. Occasional mitoses are evident in the basal and parabasal cell layers. Above the basal zone, the epithelial cells are larger and become progressively flattened but, even on the surface, they retain their nuclei. Keratohyaline granules are not usually present in the surface cells of the normal epithelium. However, glycogen is abundant. Ki-67 (monoclonal antibody MIB-1) immunostaining usually shows a negative reaction in the basal layer, on the basement membrane, and a positive reaction in the parabasal layers. Epithelial stem cells may be present in the basal layer. The presence of Ki-67-positive cells in more than three cell layers is an abnormal feature, consistent with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (Figure 1.3).

Single intra-epithelial lymphocytes (‘squiggle’ cells) lying between the squamous cells are common, particularly in the lower half of the mucosa, and in this situation their convoluted nuclei may be confused with the nuclei of neutrophils. They are a normal feature. Characterisation using monoclonal antibodies has shown them to be T lymphocytes [3]. Langerhans’ cells are antigen-presenting cells that are demonstrable, by electron microscopy and metal impregnation techniques, as sparsely distributed ovoid forms with radiating dendritic processes, occurring in all layers of the oesophageal epithelium [4]. They are positively stained with antibodies against S-100 protein and react with monoclonal antibodies against HLA-DR (major histocompatibility complex [MHC] class II) and OKT6 (CD1). They also contain calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), which may serve as an immunomodulator. The number of Langerhans’ cells and the intensity of their immunoreactivity for CGRP are increased in reflux oesophagitis [5]. They contain Langerhans’ granules (Birbeck’s granules), seen on electron microscopic examination.

Both melanocytes and non-melanocyte argyrophil cells are randomly distributed in the basal layer of the epithelium, the former usually as small groups and the latter singly [6,7]. These cell types are presumably the origin of primary malignant melanomas and small cell undifferentiated (oat cell) carcinomas, respectively, that occur at this site. Merkel’s cells are also present in the epithelium.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) studies of the squamous epithelium have broadened our understanding of the micro-anatomy [8–13]. Basal cells are cuboidal or columnar with large, centrally placed nuclei and relatively simple cytoplasm containing few organelles. They are attached to the basement membrane by frequent hemi-desmosomes. Prickle cells show numerous keratin filaments, relatively abundant glycogen, a prominent Golgi apparatus and more numerous desmosomes. The squamous cells of the superficial or functional zone become increasingly flattened towards the lumen, contain some phospholipid material and have a coating of acid mucosubstance which is likely to have a protective function. Scanning electron microscopy shows a complex pattern of micro-ridges lining the lumen. Membrane-coated granules, 0.1–0.3 µm in diameter, are present in the intermediate and superficial zones of the oesophageal epithelium. As well as being the source of mucosubstances, they also contain acid hydrolases which, when secreted into the intercellular space, may be responsible for the reduction of desmosomes exhibited by squamous cells as they approach the luminal surface.

Free-ending nerves are located in the intercellular spaces of the squamous epithelium and reach the subepithelial nerve plexus. These nerves probably mediate oesophageal pain. Cell proliferation studies have demonstrated a slower cell cycle time in basal cells overlying papillae, in comparison with the interpapillary basal cells [14]. The turnover time of the oesophageal epithelium is about 4–7 days in rats and mice. The corresponding period in humans is said t...