![]()

ANSWERS TO WRITTEN QUESTIONS

ADDRESSED TO MISS NIGHTINGALE BY THE COMMISSIONERS APPOINTED TO INQUIRE INTO THE

Regulations affecting the Sanitary Condition of the Army.

Reprinted (with some alterations) from the Report of the Royal Commission.

I.—SANITARY STATE OF THE ARMY AND HOSPITALS.

HAVE you, for several years, devoted attention to the organization of civil and military hospitals?

Yes, for thirteen years.

What British and foreign hospitals have you visited?

I have visited all the hospitals in London, Dublin, and Edinburgh, many county hospitals, some of the naval and military hospitals in England; all the hospitals in Paris, and studied with the ‘sœurs de charité;’ the Institution of protestant deaconesses at Kaiserswerth, on the Rhine, where I was twice in training as a nurse; the hospitals at Berlin, and many others in Germany, at Lyons, Rome, Alexandria, Constantinople, Brussels; also the war hospitals of the French and Sardinians.

When were you sent out to the British war hospitals at Constantinople?

We arrived at Constantinople on November 4, 1854, the eve of the Battle of Inker mann.

What hospitals did you find occupied there by the British?

Two large buildings on the Asiatic side, near Scutari, viz., a Turkish barrack and a Turkish military general hospital, both of which had been given over by the Turkish government for the use of the British troops.

How many patients did they contain at that date?

The Barrack contained 1500, the General hospital 800 patients, total 2300.

By how many nurses and ladies were you accompanied ?

By 20 nurses, 8 Anglican ‘sisters,’ 10 nuns, and 1 other lady.

Where did you take up your residence?

We were quartered the same evening in the Barrack hospital, and two months afterwards, a reinforcement of 47 nurses and ladies having been received from England, we had additional quarters assigned us in the general hospital, and later at Koulali.

How long did you reside in those hospitals?

Till the evacuation of Turkey by the British, July 28, 1856.

Did you visit the hospitals in the Crimea?

Three times. I visited the regimental hospitals; I remained in the Crimean general hospitals about six months.

For what purpose did you visit the Crimea?

Each time to place or to reinforce nurses in the Crimean general hospitals. The first time, for the General and Castle hospitals at Balaclava; the second, for the Castle and Monastery hospitals; the third, for the two land transport general hospitals, for which nurses had been ‘required’ by the principal medical officer of the army in the east.

Was that purpose effected?

Yes; although difficulties sometimes interrupted the work.

To ascertain the efficiency of the sanitary or medical organization of the army, it should be tested by its results in peace and in war?

Certainly, in both.

What tests under those two conditions exist, and are available for our instruction, particularly in reference to the state of war?

The barrack, and the military hospital exist at home and in the colonies as tests of our sanitary condition in peace; and the histories of the Peninsular war, of Walcheren, and of the late Crimean expedition, exist as tests of our sanitary condition in the state of war.

Is it necessary that you should refer at all to the hospitals of Scutari, or to the Crimea, as inquiries on these subjects have already been instituted?

We have much more information on the sanitary history of the Crimean campaign than we have on any other. It is a complete example—history does not afford its equal—of an army, after a great disaster arising from neglects, having been brought into the highest state of health and efficiency. It is the whole experiment on a colossal scale. In all other examples, the last step has been wanting to complete the solution of the problem.

We had, in the first seven months of the Crimean campaign, a mortality among the troops at the rate of 60 per cent, per annum from disease alone,—a rate of mortality which exceeds that of the great plague in the population of London, and a higher ratio than the mortality in cholera to the attacks; that is to say, that there died out of the army in the Crimea an annual rate greater than ordinarily die in time of pestilence out of sick.

We had, during the last six months of the war, a mortality among our sick not much more than that among our healthy Guards at home, and a mortality among our troops in the last five months two-thirds only of what it is among our troops at home.

The mortality among troops of the line at home, when corrected as it ought to be according to the proportion of different ages in the service, has been, on an average of 10 years, 187 per 1000 per annum; and among the Guards, 20.4 per 1000 per annum. Comparing this with the Crimean mortality for the last six months of our occupation, we find that the deaths to admissions were 24 per 1000 per annum; and, during live months, viz., January—May, 1856, the mortality among the troops in the Crimea did not exceed 11.5 per 1000 per annum.

Is not this the most complete experiment in army hygiene?

We cannot try this experiment over again for the benefit of inquirers at home, like a chemical experiment. It must be brought forward as a historical example.

Will you now state as nearly as you can how many sich and wounded soldiers were received in the hospitals which you have named at Scutari?

From June, 1854, to June, 1856, about 31,000 are said, according to the Adjutant-General’s Returns, made up at the time, 41,000, according to the Director-General’s Returns, made up subsequently, to have been admitted at the two hospitals at Scutari above mentioned, to which a third and a smaller one was added, the palace of the Sultan at Haida Pacha, near Scutari, also two ships for convalescents in the Golden Horn at Constantinople, a very small hospital for the artillery stationed at Pera, and a ward over a cavalry stable at Scutari. A certain number of cases also went to the hospitals of Smyrna, Koulali, Abydos, and Renkioi.*

What was the prevailing character of the diseases?

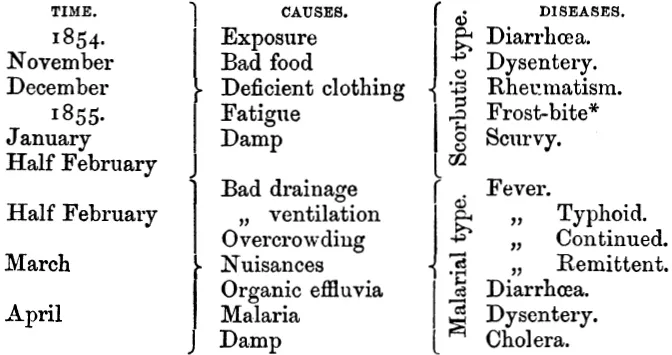

The types of disease, with their causes, may be arranged as follow:—

Did it appear to you that many diseases were induced, and others were aggravated in those hospitals?

Typhus attacked both sick and well in hospital. During the month of November, 1854, alone, we had 80 recorded cases of hospital gangrene. Out of 44 secondary amputations of the lower extremities, 36 have died. Cholera broke out frequently both among sick and well. Also, there were frequent relapses of fever and diarrhœa, and the wounded suffered much from both, and, having come in for wounds, they frequently died from fever or diarrhœa.

How many British soldiers died in those hospitals during the period of your residence?

About 4600.

Can you state the number of deaths, month by month, in those hospitals; and the maximum of deaths on any one day?

The following is the head roll of burials for Scutari alone, not including civilians:—

| November, 1854 | 368 |

| December | 667 |

| January, 1855 | 1473 |

| February | 1151 |

| March | 418 |

| April | 169 |

| May | 76 |

| June | 49 |

| July | 63 |

| August | 60 |

| September | 47 |

| October | 46 |

| †November | 25 |

| December | 7 |

| January, 1856 | 4 |

| February | 4 |

| March | 3 |

| April | 2 |

| May | 1 |

| June | 0 |

| July | 1 |

| | 4634 |

The greatest number of burials on any one day was on January 25, viz., 71. On January 26, it ...