![]()

1 NOTAN IN EVERYDAY LIFE

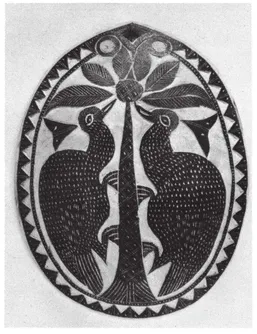

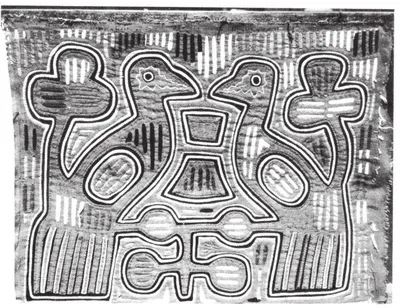

5 Carved and dyed calabash from Oyo, western Nigeria. Although the composition is symmetrical and fixed, the birds seem to be climbing because of the movement implicit in the negative shapes between their feet and the tree.

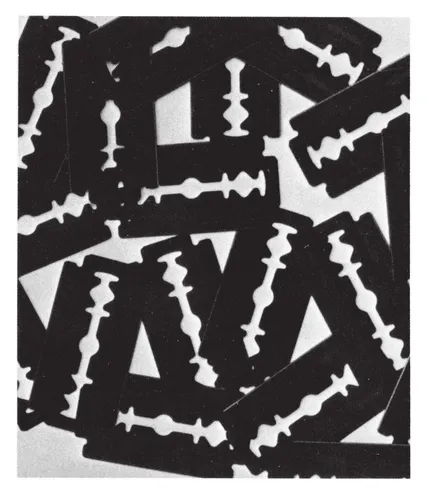

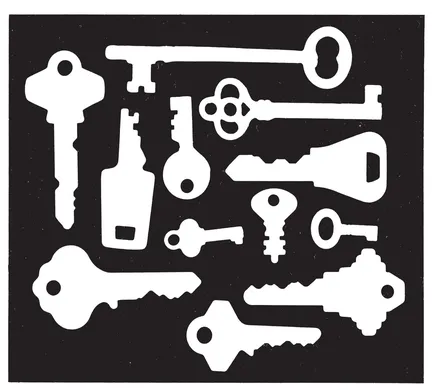

Notan appears in useful objects such as tools in both a primitive culture as well as in a modern technology. In the latter case, however, the Notan produced is more often a by-product of utility. Scissors (Fig. 79) for instance, have beautiful Notan because they must be designed with spaces to fit the fingers; keys must have holes for chains (Fig. 15), and razor blades must fit into the razor (Fig. 8). The negative space exists in these cases because of the requirements of utility, but is not necessarily an intrinsic element of the design.

Many of the examples of Notan illustrated in this book are taken from folk art. Indeed, the instinctive use of Notan in folk or “primitive” art is an almost invariable characteristic. The intuitive or folk artist, unlike the formally trained designer in modern society, does not have to be taught to remember the negative or to see it in balance with the positive. He has not been taught to seek to dominate nature or to conquer it; on the contrary, he feels himself a part of nature, and his work reflects that sense of balance.

The primitive and the modern artist also differ in their approach to decoration. In modern technology decoration is often only added as though it were an afterthought to attract the buyer’s eye. It can often be an unessential feature and in no way united with the form. The Pueblo Indian craftsman, however, who decided to decorate the simple dish with a bird (Fig. 13) was very much concerned with the integration of form and decoration. Working within the confines of the shape of the plate, he succeeded in designing a bird that would become an inseparable part of the whole or a design in which the spaces around the bird would assume a form with an exchange of positive and negative. In good design like this, the only right solution is one which finds such a union of decoration and form. And when this is discovered, the negative space will no longer be “empty,” but, instead, there will be Notan.

The primitive artist also differs from the sophisticated artist in his use of symbolic decoration. In the United States symbolic decoration has practically disappeared except in religious objects and in Pennsylvania Dutch hex signs. Yet the first impulse of the primitive artist is to use symbols. Because symbolism dictates further restrictions in both the decoration and the form of the object, the resulting design often involves a very good exchange of negative-positive.

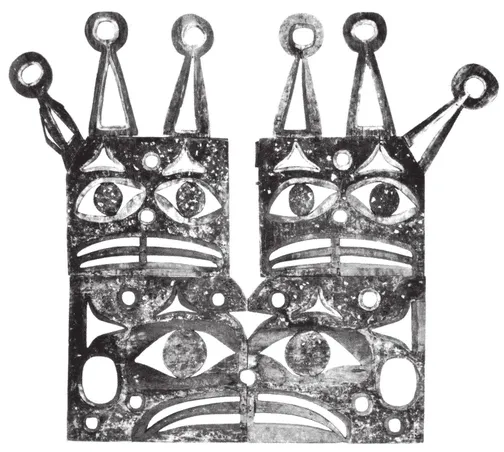

6 Kwakiutl Mechanical Screen. This screen was used in a ceremony in which a female war dancer returned from the woods possessed by the mythical and changeable sisiutl spirit. The screen’s design represents the human face, which is always in the middle of the sisiutl with its two serpent heads at either end. The screen, made to rise from a pit in the house in which the ceremony was held, was struck by the dancer with her sword, causing the two halves to split apart and seemingly disappear. Collected by Samuel A. Barrett in 1916. Wood, traces of mica, black, white, and red paint. Height 61 inches, including projecting horns. Lent by the Milwaukee Public Museum. (18060) Photograph courtesy of Dr. Albert B. Elsasser, co-author with Dr. Michael J. Harner of Art of the Northwest Coast.

An excellent example of this achievement may be seen in the Kwakiutl mechanical screen (Fig. 6). The “distortions” and the Notan here resulted from the creation of a design within the restrictions of the materials and the ritual use of the screen. It had to be made of wood sturdy enough to stand, and it had to incorporate a slot together with hinges so that it would open and fall when struck by the sword. Yet the triumph of the screen is that the “distortions” or modifications not only brought about the stark dramatic contrasts of the Notan, but also the accomplishment of the artist’s main purpose: the creation of a work of great dramatic and ritualistic power.

7 Stove “cooling” shelf. These shelves extended to the right of the cooking surface. Many manufacturers took advantage of the space to show the initials of the company (center) and the name of the stove model. Made around 1890. The Notan here was the result of necessity.

8 Though the openings of these razor blades are utilitarian, when seen as Notan they become decorative units working with the white negative spaces to form an interesting pattern.

9 Circus number. This large (36 by 24 inch) lithographed number was printed around 1890. In those days circus posters were put up well in advance without dates. The exact date, such as this three, was pasted on when the show reached an adjoining town. The negative spaces were carefully designed to make the number readable at a great distance.

10 A symmetrical paper cutout from Poland with fine interplay between the negative spaces. A good example of instinctive Notan.

11 Stove shelf made around 1900 showing “Art Nouveau” influence. Here the heaving scroll dominates, and the negative spaces are monotonously uniform in size and shape.

12 Applique stitchery, San Blas Indian work, Panama. A beautiful integration of birds, plant, and the spaces surrounding them.

13 Clay dish. Pueblo Indian work, Acoma, New Mexico. The symmetry of this design is relieved by the turn of the bird’s head. The distribution of the pattern is dictated by symbolic meaning.

14 Sword guard of wrought iron. Japanese, circa 1800. This nineteenth century Japanese sword guard is ornamented by negative space—for the iron is decorated only by its symmetrically arranged openings. M. H. De Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco, California.

The problems imposed by the limitations or restrictions of materials also serve to distinguish the trained modern artist from the primitive one; and again this endeavor relates to the development of Notan. The folk or primitive artist finds himself bound by a narrow range of materials and has little choice but to work within the limitations of his medium. However, since his attitude is such that he does not feel impelled to conquer nature, he is able to work with nature; indeed, he employs the restrictions of his materials to discover his design.

The African decorator of the calabash (Fig. 5) made a simple design that is definitely integrated with the oval shape of the calabash. Nothing is hidden—the rim of the wood is exposed; it is easy to see the basic material. The same may be said of the Pueblo plate; the decoration was not intended to camouflage the plate.

In America before the technical revolution, the designer’s major concern was that of overcoming the deficiencies of his materials. There was the design problem, for instance, of the “cooling” shelf on the cast-iron stoves so popular in the nineteenth century. Since the cooking was done in a cast-iron kettle on a wood or coal stove where the fire could not be reduced rapidly, it was necessary to move the kettle to a cooling shelf that permitted the circulation of air; the holes designed for this purpose led to the creation of Notan in a design made as beautiful as possible in the style of an age of fanciful decor. But the designer’s purpose was to hold together the holes of the stove shelf.

A similar problem faced the designers of the Japanese sword guards of a much earlier period. Iron was used because of its ritual significance, but in order to preserve the balance of the sword, it was necessary to subtract weight from the material. This necessity was again met by cutting holes—but the Notan resulted from the search for symbolic designs. Between the requirements of ritual and the limitations of the material, Notan was created.

The designer in a technology faces few limitations in his choice of materials or tools; he has any number of choices to make and he often makes poor ones. His is the dilemma of freedom; it sometimes produces wonderful things, but also sometimes the grotesque. And because the skills of the modern designer are not as challenged as they would be by greater restrictions, he must more consciously seek to produce Notan.

15 The holes in the keys set up a visual rhythm with the varied spaces in between the keys and the keys themselves. This rhythmic interplay is the basis of Notan.

In order to challenge and to discipline the skills of the modern design student, the problem-solving approach used in this text has set up restrictions that imitate the working situation of the primitive artist. These restrictions appear as limitations of materials (the use of only black and gray construction paper, a white format, scissors and glue) and in the design problems (i.e., “Within a given format, arrange five circular shapes having a sequence of size to produce asymmetrical balance ”).

Because the solving of these problems involves discipline and results in a sense of achievement, the student should, at the conclusion of this course of work, approach his own future design problems with an entirely new method and spirit. Although all the problems presented here are two-dimensional, the implications for three-dimensional design should become apparent. Moreover, no matter what field of art the student enters, or is presently engaged in, he will, at the completion of this course of work, approach his problems first and last for Notan.

The artist working in photography, painting, or printmaking will no longer continue to see the background as mere support for his subject, but will realize that the background can be as dramatic as the subject. He will be forced to a new awareness of what before was considered to have no particular meaning or vitality. His idea of the relationships in his work will also be changed, and the result will be a new unity.

If he is a sculptor, he will become as interested in the shapes of open spaces as in those of solid areas; he will also seek their interaction in a unified statement. Many sculptors have utilized this knowledge in their work, the most prominent example being Henry Moore. (See Figs. 34 and 38.)

The weaver who studies Notan will begin to understand that he has been struggling with positive and negative relationships in his work all along. A closely woven tapestry can depict a two-dimensional design—abstract or figurative—which can be developed with a painter’s understanding of Notan. Much traditional pattern weaving is based on the control of positive and negative reversals, stunnin...