![]()

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

LIST OF MAPS

INTRODUCTION

1 HOW IT ALL BEGAN

2 THE SHEEP WORRIER OF EUROPE IS ON THE LOOSE

3 THE COMMANDERS

4 THE OFFICERS

5 THE SOLDIERS

6 BATTLE JOINED

7 THE CRISIS APPROACHES

8 THE BATTLE FOR EUROPE

9 THE DECISION

10 THE END

EPILOGUE

NOTES

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

![]()

ILLUSTRATIONS

SECTION ONE

Portrait of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington by Thomas Heaphy, 1813 (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

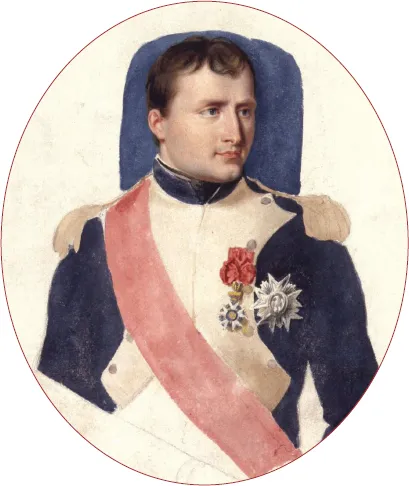

Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte by Thomas Heaphy, c.1813 (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

Portrait of Field Marshal Prince Gebhard von Blücher by Henry Alken, 1815 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

Ligny (© Imogen Corrigan)

Gemioncourt Farm (© Imogen Corrigan)

Tod des Herzog Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig by Diterich Monten, 1815 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

Papelotte Farm (© Imogen Corrigan)

La Haie Sainte (© Imogen Corrigan)

The Battle of Waterloo, published by Richard Holmes Laurie, 1819 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

The Marquis of Anglesey wounded, leading the 7th Light Hussars by Charles Turner Warren, 1819 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

French cavalry charging British Highlanders at Waterloo by William Heath, 1836 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

Battle of Waterloo by W. T. Fry, after Denis Dighton, 1815 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

The Tree of Hougoumont (© Imogen Corrigan)

The French Right Flank (© Imogen Corrigan)

Schlacht bei Waterloo am 18 Juni 1815 by Dunkler, c.1816 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

SECTION TWO

Le Caillou (© Imogen Corrigan)

Wellington’s Headquarters (© Imogen Corrigan)

Battle of Waterloo, June 18th, 1815. The Life Guards charging the Imperial Guards by Franz Josef Manskirch, 1815 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

The Farm of Mont-Saint-Jean (© Imogen Corrigan)

The Battle of Waterloo by Aleksander Sauerveid, 1819 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

La Vielle Garde à Waterloo. 8 Juin 1815 by Hippolyte Bellangé, 1869 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

Ende der glorreichen Schlacht von la Belle Alliance den 18 Juny 1815 by Fredrich Campe, 1821 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

Meeting of the Duke of Wellington and Prince Blücher at La Belle Alliance after the Battle of Waterloo by Charles Turner Warren, 1818 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

Buonapartes feige Flucht nach der Schlacht von la Belle Alliance by Fredrich Campe, 1821 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

Pursuit of the Prussians by moonlight by Charles Turner Warren, 1818 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive)

The field of Waterloo, as it appeared the morning after the memorable battle of the 18th June 1815 by John Heaviside Clark, 1817 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

Château de Hougoumont. Field of Waterloo, 1815 by Denis Dighton (Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2014)

The execution of the sentence on Marshal Ney, in the garden of the Luxemburgh at Paris, December 8th 1815 by Innocent-Louis Goubaud, 1816 (Courtesy of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Archive, Brown University Library)

![]()

MAPS

| Europe in 1815 |

| The German States, June 1815 |

| France in 1815 |

| Area of Operations: The Waterloo Campaign, 15–18 June 1815 |

| The Field of Quatre Bras, 16 June 1815 |

| The Field of Ligny, 16 June 1815 |

| The Field of Waterloo, 1300 hrs, 18 June 1815 |

| Area of Operations: Blücher and Grouchy, 18–19 June 1815 |

| The Advance to Paris, 18 June–3 July 1815 |

![]()

The Duke of Wellington by Thomas Heaphy (1775–1835). Invited to accompany the army in the Peninsula from 1813, Heaphy painted most of the senior officers and many of the soldiers. Officers were charged according to the size of the painting – full length, three-quarters length, head and shoulders, head – and Heaphy did very well out of his commissions. His portraits are considered to be the most lifelike of contemporary artists, and this one was painted in 1813.

Napoleon Bonaparte. Also by Thomas Heaphy, although this time without a sitting by the subject and presumably unpaid. Painted in 1813, by Waterloo Napoleon had put on weight and looked much older.

Field Marshal Prince Gebhard von Blücher. Commander of the Prussian Army during the Waterloo campaign and seventy-three in 1815, his relationship with Wellington was crucial to the success of the battle. While he rarely appeared in full dress uniform and medals, that is how he was visualised by ally and enemy alike. (Henry Alken, 1815)

Ligny. Looking north towards the church at Ligny from La Tombe, the prehistoric burial mound used first by General Zeithen as he brought in the Prussian rearguard, and then by Napoleon who moved from Fleurus. The main Prussian position is beyond the church along the ridge on the skyline.

Gemioncourt Farm. Gemioncourt from the south. Built around the early 1600s, it was the headquarters of Bijlandt’s Brigade at Quatre Bras until it was captured early on. A brief attempt to recapture it failed and it remained in French hands until the end of the battle.

The Death of the Duke of Brunswick. Unusually for professional soldiers of the time, the Duke hated all things French in general and Napoleon in particular. He was hit trying to rally his cavalry at Quatre Bras, carried off the field and died shortly afterwards. (Diterich Monten, 1815)

Papelotte Farm. On the extreme left of Wellington’s position at Waterloo, it was held throughout the day by Saxe-Weimar’s Dutch-Belgians. Heavily damaged during the battle, it was largely rebuilt after it.

La Haie Sainte. A farmhouse forward of the Allied centre with a roadblock of upturned carts, it was held by a battalion of the King’s German Legion against repeated attacks until about 1800 hours, when, out of ammunition, they were forced to withdraw.

The Battle of Waterloo. One of the few contemporary paintings of which the artist might just possibly have seen the ground, rather than drawing from his imagination. La Haie Sainte is on the left and La Belle Alliance on the right, although the scene of Highlanders in the valley seeing off French cavalry is entirely allegorical, and may be due to the artist confusing the Waterloo and Quatre Bras battles. (Published by Richard Holmes Laurie, 1819)

The Marquess of Anglesey leading the 7th Hussars. Henry Paget, not the Marquess of Anglesey until after Waterloo, where he was Earl of Uxbridge, was in overall command of the allied cavalry but led his own regiment with great skill in the retreat from Quatre Bras to Waterloo, where in the closing stages of the latter battle he lost a leg. (Charles Turner Warren, 1819)

French cavalry charging Highlanders at Waterloo. Steady troops in square had little to fear from cavalry, and it is unlikely that the horsemen ever got as close to the square as is depicted here. The failure of the French command and control systems to support the cavalry with artillery and infantry cost them dear. (William Heath, 1836)

The Battle of Waterloo. The almost insatiable desire of press and public to be informed of the great battle led to all sorts of dubious artistic endeavour hastily employed to show what war was like, or what the artist thought it was like.

(W. T. Fry, supposedly after Denis Dighton, 1815)

The Tree of Hougoumont. One of the very few surviving trees of the wood to the south of Hougoumont Farm. The bullet holes made by the Guards’ muskets can be seen clearly.

The French Right Flank. The area to the right of the French position at Waterloo was a maze of sunken roads. Infantry could have crossed them, cavalry could have got in but not out and guns could only be manhandled across with very great difficulty. This made any attempt by Napoleon to envelop Wellington’s left flank very unlikely.

The Battle of Waterloo. Prussian infantry on the right of the picture and French infantry on the left, probably somewhere in the vicinity of Plancenoit in the late afternoon. Artistic license shows the opposing forces far closer than they would actually have been. (Dunkler, 1816)

Le Caillou. The building in which Napoleon and his staff spent the night before Waterloo, and where he gave his final orders for the battle on the morning of 18 June. It is now a museum.

Wellington’s Headquarters. At the time of the battle, Waterloo was an insignificant hamlet on a dirt road some two miles north of the battlefield. The inn where Wellington spent the night after the battle, and where he penned the Waterloo Despatch, is now a museum in the main street of a sizeable town, which, due to ribbon development, is fast becoming a suburb of Brussels.

The Battle of Waterloo – the Life Guards charging the French Imperial Guard. There are lies, damned lies, and artists’ impressions. Both regiments of the Life Guards, seriously under-strength, were at Waterloo and they charged D’Erlon’s infantry and the French gun line as part of the Household Brigade, suffering considerable casualties as a result. It is unlikely that they ever charged the Imperial Guard, although they were charged by French lancers, which is probably what this picture actually represents, the title having been corrupted over the years. (Franz Josef Manskirch, 1815)

The Farm of Mont-Saint-Jean. Located a few hundred yards behind Wellington’s line it was the Allies’ main field hospital and also a stores depot. Piling large stocks of spare ammunition next to operating tables would probably be regarded as unwise today.

The Battle of Waterloo. Sometime near the close of the battle, Wellington is seen in the centre foreground with La Haie Sainte on the left. It would be some time before photographic evidence could show artists that horses do not canter or gallop as shown here, with both forelegs extended. It was fashionable at the time to show horses with small Arab-type heads and arched necks, which in reality few military chargers had. (Aleksander Sauerveid, 1819)

The Old Guard at Waterloo. The elite of the elite of the French army, the Guard were usually held back to pluck victory from defeat or to add a crushing blow to a battle already won. At Waterloo they were played as Napoleon’s final card, and failed, but fought a gallant rear-guard action to allow the Emperor to escape the field, thus creating a legend of French military valour that endures to this day. (Hippolyte Bellangé, 1869)

The End of the Glorious Battle of La Belle Alliance. Waterloo was La Belle Alliance to the Prussians. Here Prussian cavalry (identified by the initials ‘FW’ for Frederick William on the pistol holster of the mounted officer in the foreground) is seen chasing French infantry, including some bearskin-cap-weari...