![]()

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

A Note on Currency

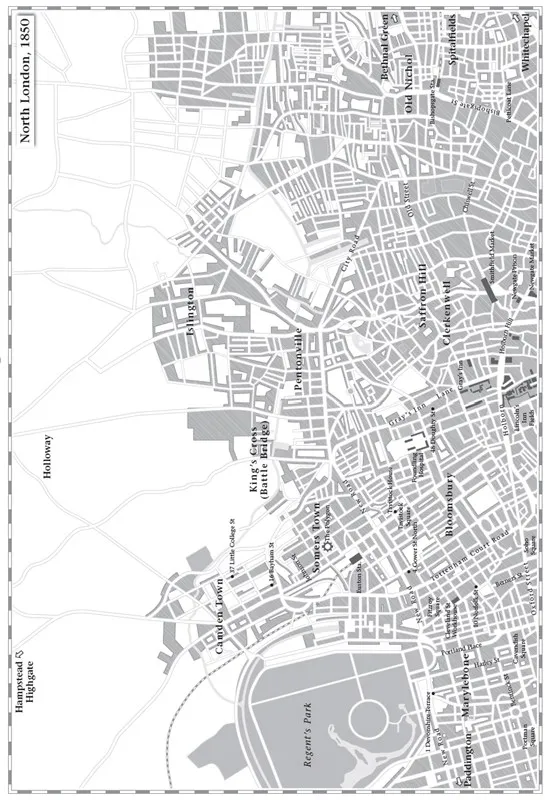

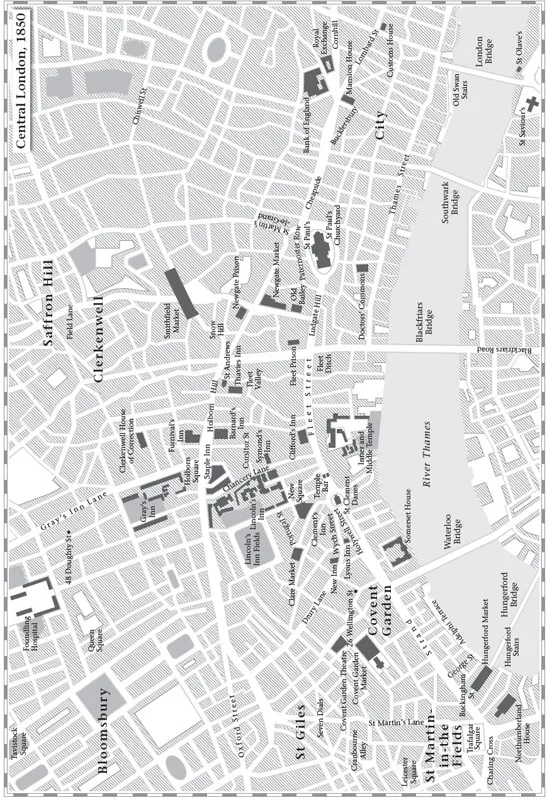

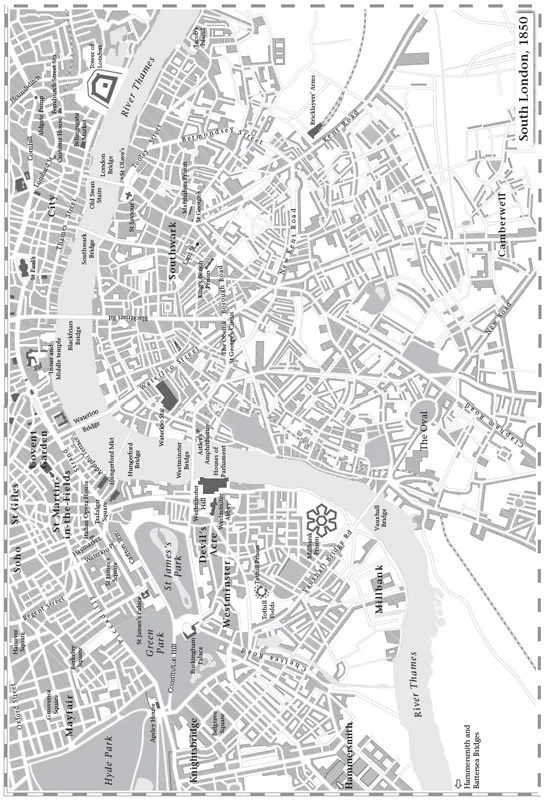

Maps

List of Illustrations

Introduction

PART ONE: THE CITY WAKES

1810: The Berners Street Hoax

1. Early to Rise

2. On the Road

3. Travelling (Mostly) Hopefully

4. In and Out of London

PART TWO: STAYING ALIVE

1861: The Tooley Street Fire

5. The World’s Market

6. Selling the Streets

7. Slumming

8. The Waters of Death

PART THREE: ENJOYING LIFE

1867: The Regent’s Park Skating Disaster

9. Street Performance

10. Leisure for All

11. Feeding the Streets

12. Street Theatre

PART FOUR: SLEEPING AND AWAKE

1852: The Funeral of the Duke of Wellington

13. Night Entertainment

14. Street Violence

15. The Red-Lit Streets to Death

Appendix: Dickens’ Publications by Period

Notes

Bibliography

Index

![]()

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is the product of a lifetime of London-loving and Dickens-loving, and I must first and foremost thank those great London and Dickens scholars who have enriched my reading: Peter Ackroyd, Philip Collins, John Drew, Madeline House, Susan Shatto, Michael Slater, Graham Storey and Kathleen Tillotson.

As always, I am indebted to the members of the Victoria 19th-century British Culture and Society mailbase for their tolerance of my seemingly random queries, and for their vast stores of knowledge. And to Patrick Leary, list-master extraordinaire, go not merely my thanks for creating such a congenial environment, but also for pointing me towards the Regent’s Park skating disaster.

I am grateful to my agent Bill Hamilton for his skill, and for his patience and tolerance.

I thank, too, all those at Atlantic Books, past and present: Alan Craig, Karen Duffy, Lauren Finger, Richard Milbank, Sarah Norman, Bunmi Oke, Sarah Pocklington, Orlando Whitfield and Corinna Zifko. My thanks too to Jeff Edwards, Douglas Matthews, Lindsay Nash, Leo Nickolls and Tamsin Shelton. The wonderful pictures were found by Josine Meijer, while Celia Levett, with her sensitive and rigorous copy-editing, improved every sentence of the text.

Finally, I owe my career to Ravi Mirchandani, now my publisher but, before I became a writer, my friend. ‘Stop talking about it,’ he told me then. ‘Write it.’ So I have. This book is for him.

![]()

A NOTE ON CURRENCY

Pounds, shillings and pence were the divisions of the currency. One shilling is made up of twelve pence; one pound of twenty shillings, i.e. 240 pence. Pounds are represented by the £ symbol, shillings as ‘s’, and pence as ‘d’ (from the Latin, denarius). ‘One pound, one shilling and one penny’ is written as £1 1s 1d. ‘One shilling and sixpence’, referred to in speech as ‘one and six’, is written as 1s 6d, or ‘1/6’.

A guinea was a coin to the value of £1 1 0. (The actual coin was not circulated after 1813, although the term remained and tended to be reserved for luxury goods.) A sovereign was a twenty-shilling coin, a half-sovereign a tenshilling coin. A crown was five shillings, half a crown 2/6, and the remaining coins were a florin (two shillings), sixpence, a groat (four pence), a threepenny bit (pronounced ‘thrup’ny’), twopence (pronounced tuppence), a penny, a halfpenny (pronounced hayp’ny), a farthing (a quarter of a penny) and a half a farthing (an eighth of a penny).

Relative values have altered so substantially that attempts to convert nineteenth-century prices into contemporary ones are usually futile. However, the website http://www.ex.ac.uk/~RDavies/arian/current/howmuch.html is a gateway to this complicated subject.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Street traders, sketches by George Scharf, 1841 (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Two drawings of wooden street paving by George Scharf, 1838 and 1840 respectively (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Anonymous photo of the Kennington turnpike gate, c.1865 (London Metropolitan Archives)

Figures with water carts at a pump in Bloomsbury Square. Drawing by George Scharf, 1828 (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Construction of the Holborn Viaduct. Anonymous engraving, 1867 (© Illustrated London News/ Mary Evans Picture Library)

Departure of the Army Works Corp from London for the Crimea. Anonymous engraving, 1855 (© Illustrated London News/ Mary Evans Picture Library)

The Omnibus brutes…which are they? By George Cruikshank, 1835 (© Look and Learn/ Peter Jackson Collection)

Anonymous photo of hansom cabs in Whitehall Place, Westminster, 1870–1900 (© English Heritage. NMR)

Royal Mail Coaches leaving The Swan with Two Necks Inn, Lad Lane. Engraving by F. Rosenberg after James Pollard, 1831 (Guildhall Library, City of London/ Bridgeman Art Library)

Station Commotion. Engraving by W. Shearer after a drawing by William McConnell, 1860 (Getty Images)

Parliamentary Train: Interior of the Third Class Carriage. Undated lithograph by William McConnell from ‘Twice Around the Clock’ (© Look and Learn/ Peter Jackson Collection/ Bridgeman Art Library)

Plan of Buildings destroyed at Chamberlain’s Wharf, Cotton’s Wharf and Hay’s Wharf. Lithograph by James Thomas Loveday, 1861 (© Guildhall Library, City of London/ Bridgeman Art Library)

The funeral procession of James Braidwood. Anonymous engraving, 1861 (© London Fire Brigade)

The construction of Hungerford Market. Drawing by George Scharf, 1832 (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Anonymous photo of a London match seller in Greenwich, 1884 (Francis Frith Collection/ Mary Evans Picture Library)

The Fleet Prison, watercolour by George Shepherd, 1814 (Greater London Council Print Collection)

Interior of a lodging house. Anonymous engraving, 1853 (© Illustrated London News/ Mary Evans Picture Library)

View from Jacob’s Island of old houses in London Street, Dockhead. Anonymous engraving, 1810 (Wellcome Library, London)

The water supply in Frying Pan Alley, Clerkenwell. Anonymous engraving, 1864 (Private Collection/ Bridgeman Art Library)

The Chelsea Embankment looking East. Photo by James Hedderly, c. 1873 (Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Libraries)

Street musicians. Sketches by George Scharf, 1833 (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Joseph Johnson with his Nelson hat. Engraving by John Thomas Smith, 1815. (From: John Thomas Smith, ‘Vagabondiana’, Chatto & Windus, London 1874)

Northumberland House. Anonymous, undated engraving (© Museum of London)

Hot-potato seller. Sketch by George Scharf, 1820–1830 (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Dinner Time, Sunday One O’Clock. Sketches by George Scharf, 1841 (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

The City Chop House. Print by Thomas Rowlandson, 1810–1815 (© Museum of London)

Crowds watching the house of Robert Peel. Anonymous engraving, 1850 (© Illustrated London News/ Mary Evans Picture Library)

Episode During a Brief Visit to London. Anonymous engraving, 1885 (Private Collection/ Bridgeman Art Library)

Anonymous photo of the nineteenth century Willesden Fire Brigade (© London Fire Brigade)

Scene in a London street on a Sunday morning. Anonymous engraving, 1850 (© Museum of London)

The Coal Hole, undated watercolour by Thomas Rowlandson (Blackburn Museums and Art Galleries/ Bridgeman Art Library)

Peace illuminations in Pall Mall at the end of the Crimean War. Anonymous engraving, 1856 (© Illustrated London News/ Mary Evans Picture Library)

Scaffold outside Newgate Prison. Anonymous print, 1846 (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Capture of the Cato Street Conspirators. Engraving after a drawing by George Cruikshank, 1820 (Peter Higginbotham Collection/ Mary Evans Picture Library)

Haymarket prostitutes. Anonymous engraving, c.1860 (Mary Evans Picture Library)

Ernest Boulton and Frederick Park arrested for wearing women’s clothes. Anonymous engraving, 1870 (Mary Evans Picture Library)

Illustration to Thomas Hood’s poem ‘The Bridge of Sighs’ by Gustave Doré (From: Thomas Hood, Hood’s Poetical Works, 1888)

1. Benjamin Robert Haydon, Punch, or May Day, 1829. Oil on canvas. Tate Gallery, London (© Tate, London 2012)

2. Eugène Louis Lami, Ludgate Circus, 1850. Watercolour drawing. Victoria & Albert Museum, London (© Victoria & Albert Museum, London)

3. William Parrott, Pool of London from London Bridge, 1841. Lithograph (Guildhall Library, City of London/ Bridgeman Art Library)

4. George Scharf, Betwen 6 and Seven O’Clock morning, Sumer, undated. Drawing. British Museum (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

5. Thomas Rowlandson, A Peep at the Gas Lights in Pall Mall, undated. (Guildhall Library, City of London/ Bridgeman Art Library)

6. George Cruikshank, Foggy Weather, 1819. Hand-coloured etching. British Museum (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

7. Anonymous lithograph, The Tooley Street Fire, 1861. Museum of London (© Museum of London)

8. Frederick Christian Lewis, Covent Garden Market, c.1829. Oil on canvas. (Reproduced by kind permission of His Grace the Duke of Bedford and the Trustees of the Bedford Estates, and that copyright remains with His Grace the Duke of Bedford and the Trustees of the Bedford Estates)

9. George Shepherd, Hungerford Stairs, 1810. Watercolour. (Guildhall Library, City of London/ Bridgeman Art Library)

10. E. H. Dixon, The Great Dust-Heap, 1837. Watercolour. (Wellcome Library, London)

11. Fox Talbot, Nelson’s Column Under Construction, c.1841. Photograph. (Stapleton Collection/ Bridgeman Art Library)

12. George Scharf, Building the New Fleet Sewer, undated. Drawing. British Museum (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

13. George Scharf, Workmen on London Bridge, 1830. Drawing. The British Library. (© The British Library Board)

14. George Scharf, Old Murphy, 1830. Watercolour. The British Library. (© The British Library Board)

15. George Scharf, Chimney Sweeps Dancing on Mayday, undated. Watercolour. British Museum. (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

16. George Scharf, The Strand from Villiers Street, 1824. Watercolour. British Museum (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

17. Henry Alken, Funeral Car of the Duke of Wellington, 1853. Coloured engraving. (Victoria & Albert Museum, London/Bridgeman Art Library)

18. William Heath, Greedy Old Nickford Eating Oysters, late 1820s. Hand-coloured etching. British Museum. (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

19. Henry Alken, Bear Baiting, 1821. Coloured engraving. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

20. Rowlandson & Pugin, Charing Cross Pillory, 1809. Aquatint. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

21. George Cruikshank, Acting Magistrates Committing Themselves being Their First Appearance on this Stage as Performed at the National Theatre Covent Garden, 1809. Hand-coloured etching. British Museum. (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

![]()

INTRODUCTION

‘A Dickensian scandal for the 21st century’ blares one newspaper headline. ‘No one should have to live in such Dickensian conditions,’ says another. Today ‘Dickensian’ means squalor, it means wretched living conditions, oppression and darkness.

Yet Dickens finished his first novel with a glance at the sunny Mr Pickwick and his friends: ‘There are dark shadows on the earth, but its lights are stronger in the contrast. Some men, like bats or owls, have better eyes for the darkness than for the light. We, who have no such optical powers, are better pleased to take our last parting look at the visionary companions of many solitary hours, when the brief sunshine of the world is blazing full upon them.’ The brief sunshine of the world blazed out in full in Dickens’ work and, early in his career in particular, that was the way his contemporaries saw it. For them, ‘Dickensian’ meant comic; for others, it meant convivial good cheer.1 It was not until the twentieth century, as social conditions began to improve, that ‘Dickensian’ took on its dark tinge. In Dickens’ own time, the way that people lived was not Dickensian, merely life.

The ...