eBook - ePub

A Splendid Exchange

How Trade Shaped the World

William L Bernstein

This is a test

Buch teilen

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

A Splendid Exchange

How Trade Shaped the World

William L Bernstein

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

A Splendid Exchange tells the epic story of global commerce, from its prehistoric origins to the myriad crises confronting it today. It travels from the sugar rush that brought the British to Jamaica in the seventeenth century to our current debates over globalization, from the silk route between China and Rome in the second century to the rise and fall of the Portuguese monopoly in spices in the sixteenth. Throughout, William Bernstein examines how our age-old dependency on trade has contributed to our planet's agricultural bounty, stimulated intellectual and industrial progress and made us both prosperous and vulnerable.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist A Splendid Exchange als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu A Splendid Exchange von William L Bernstein im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Historia & Historia del mundo. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

HistoriaThema

Historia del mundoCONTENTS

List of Maps

Introduction

1 Sumer

2 The Straits of Trade

3 Camels, Perfumes, and Prophets

4 The Baghdad-Canton Express

5 The Taste of Trade and the Captives of Trade

6 The Disease of Trade

7 Da Gama’s Urge

8 A World Encompassed

9 The Coming of Corporations

10 Transplants

11 The Triumph and Tragedy of Free Trade

12 What Henry Bessemer Wrought

13 Collapse

14 The Battle of Seattle

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Illustration Credits

Index

MAPS

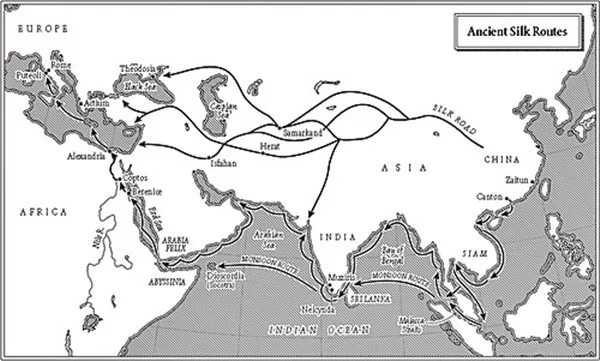

Ancient Silk Routes

World Trade System, Third Millennium BC

Ancient Canals at Suez

Winter Monsoon Winds and Summer Monsoon Winds

Athenian Grain Routes

Incense Lands and Routes

The World of Medieval Trade

The Spice Islands

Eastern Mediterranean Spice/Slave Trade, Circa AD 1250

The Black Death, Act I: AD 540–800

The Black Death, Act II: 1330–1350

The Tordesillas Line in the West

Da Gama’s First Voyage, 1497–1499

The Global Wind Machine

Banda (Nutmeg) Islands

Strait of Hormuz

Dutch Empire in Asia at its Height in the Seventeenth Century

Coffee-Growing Area and Ports of Late-Medieval Yemen

The Sugar Islands

Pearl River Estuary

The Erie Canal and Saint Lawrence Systems in 1846

World Oil Flows, Millions of Barrels per Day

INTRODUCTION

The circumstances could not have been more ordinary: a September morning in a hotel lobby in central Berlin. While the desk clerk and I politely exchanged greetings in each other’s fractured English and German, I casually plucked an apple from the bowl on the counter and slipped it into my backpack. When hunger overtook me a few hours later, I decided on a quick snack in the Tiergarten. The sights and sounds of this great urban park nearly made me miss the tiny label that proclaimed my complimentary lunch a “Product of New Zealand.”

Televisions from Taiwan, lettuce from Mexico, shirts from China, and tools from India are so ubiquitous that it is easy to forget how recent such miracles of commerce are. What better symbolizes the epic of global trade than my apple from the other side of the world, consumed at the exact moment that its ripe European cousins were being picked from their trees?

Millennia ago, only the most prized merchandise—silk, gold and silver, spices, jewels, porcelains, and medicines—traveled between continents. The mere fact that a commodity came from a distant land imbued it with mystery, romance, and status. If the time were the third century after Christ and the place were Rome, the luxury import par excellence would have been Chinese silk. History celebrates the greatest of Roman emperors for their vast conquests, civic architecture, engineering, and legal institutions, but Elagabalus, who ruled from AD 218 to 222, is remembered, to the extent that he is remembered at all, for his outrageous behavior and his fondness for young boys and silk. During his reign he managed to shock the jaded populace of the ancient world’s capital with a parade of scandalous acts, ranging from harmless pranks to the capricious murder of children. Nothing, however, commanded Rome’s attention (and fired its envy) as much as his wardrobe and the lengths he went to flaunt it, such as removing all his body hair and powdering his face with red and white makeup. Although his favorite fabric was occasionally mixed with linen—the so-called sericum—Elagabalus was the first Western leader to wear clothes made entirely of silk.1

From its birthplace in East Asia to its last port of call in ancient Rome, only the ruling classes could afford the excretion of the tiny invertebrate Bombyx mori—the silkworm. The modern reader, spoiled by inexpensive, smooth, comfortable synthetic fabrics, should imagine clothing made predominantly from three materials: cheap, but hot, heavy animal skins; scratchy wool; or wrinkled, white linen. (Cotton, though available from India and Egypt, was more difficult to produce, and thus likely more expensive, than even silk.) In a world with such a limited sartorial palette, the gentle, almost weightless caress of silk on bare skin would have seduced all who felt it. It is not difficult to imagine the first silk merchants, at each port and caravanserai along the way, pulling a colorful swatch of it from a pouch and turning to the lady of the house with a sly, “Madam, you must feel this to believe it.”

The poet Juvenal, writing around AD 110, complained of luxury-loving women “who find the thinnest of thin robes too hot for them; whose delicate flesh is chafed by the finest of silk tissue.”2 The gods themselves could not resist: Isis was said to have draped herself in “fine silk yielding diverse colors, sometime yellow, sometime rose, sometime flamy, and sometime (which troubled my spirit sore) dark and obscure.”3

Although the Romans knew Chinese silk, they knew not China. They believed that silk grew directly on the mulberry tree, not realizing that the leaves were merely the worm’s home and its food.

How did goods get from China to Rome? Very slowly and very perilously, one laborious stage at a time.4 Chinese traders from southern ports loaded their ships with silk for the long coastwise journey down Indochina and around the Malay Peninsula and Bay of Bengal to the ports of Sri Lanka. There, they would be met by Indian merchants who would then transport the fabric to the Tamil ports on the southwest coast of the subcontinent—Muziris, Nelcynda, and Comara. Here, large numbers of Greek and Arab intermediaries handled the onward leg to the island of Dioscordia (modern Socotra), a bubbling masala of Arab, Greek, Indian, Persian, and Ethiopian entrepreneurs. From Dioscordia, the cargo floated on Greek vessels through the entrance of the Red Sea at the Bab el Mandeb (Arabic for “Gate of Sorrows”) to the sea’s main port of Berenice in Egypt; then across the desert by camel to the Nile; and next by ship downstream to Alexandria, where Greek Roman and Italian Roman ships moved it across the Mediterranean to the huge Roman termini of Puteoli (modern Pozzuoli) and Ostia. As a general rule, the Chinese seldom ventured west of Sri Lanka, the Indians north of the Red Sea mouth, and the Italians south of Alexandria. It was left to the Greeks, who ranged freely from India to Italy, to carry the greatest share of the traffic.

Ancient Silk Routes

With each long and dangerous stage of the journey, silk would change hands at dramatically higher prices. It was costly enough in China; in Rome, it was yet a hundred times costlier—worth its weight in gold, so expensive that even a few ounces might consume a year of an average man’s wages.5 Only the wealthiest, such as Emperor Elagabalus, could afford an entire toga made from it.

The other way to Rome, the famous Silk Road, first opened up by Han emissaries in the second century of the Christian era, bumped slowly overland through central Asia. This route was far more complex, and its precise track varied widely with shifting political and military conditions, from well south of the Khyber Pass to as far north as the southern border of Siberia. Just as the sea route was dominated by Greek, Ethiopian, and Indian traders, so would be the overland “ports,” the great cities of Samarkand (in present-day Uzbekistan), Isfahan (in Iran), and Herat (in Afghanistan), richly served by Jewish, Armenian, and Syrian middlemen. Who, then, could blame the Romans for thinking that silk was manufactured in two different nations—a northern one, Seres, reached by the dry route; and a southern one, Sinae, reached by water?

The sea route was cheaper, safer, and faster than overland transport, and in the premodern world had the added advantage of bypassing unstable areas. Silk originally reached Europe via the land route, but the stability of the early Roman Empire increasingly made the Indian Ocean the preferred conduit between East and West for most commodities, silk included. Although Roman commerce with the East tapered off during the second century, the maritime route would remain open until Islam severed it in the seventh century.

The seasonal metronome of the monsoon winds drove the silk trade. The monsoons also dictated that at least eighteen months separated the embarkation of the fabric from south China and its arrival at Ostia or Puteoli. Mortal peril awaited the merchant at every point, especially in the hazardous stretches of the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal. The loss of lives, bottoms, and cargoes was so routine that such tragedies were usually recorded, if at all, with the short notation: “Lost with all hands.”

Today, the most ordinary cargoes span such distances with only a modest increase in price. That the efficient intercontinental transport of even bulk goods today seems so unremarkable is in itself remarkable.

Our high-value items fly around the globe at nearly the speed of sound, conveyed by crews manning air-conditioned cockpits and greeted at journey’s end with taxis and four-star hotels. Even those tending bulk cargoes serve on vessels stocked with videos and bulging pantries that provide a degree of safety and comfort unimaginable to the premodern sailor. Today’s aircraft and freighter crews are highly skilled professionals, but few would recognize them as “traders.” Neither would most of us apply that term to the multinational corporate sellers and buyers of the world’s cornucopia of commerce.

Not so long ago, the trader was simple to identify. He bought and sold goods in small amounts for his own account, and he accompanied them every step of the way. On board ship, he usually slept on his cargo. Although most of these traders left us with no written records, a vivid window into premodern long-distance commerce can be found in the Geniza papers, a collection of medieval records stumbled on in a storage room adjacent to Cairo’s ancient main synagogue. Jewish law required that no document containing the name of God be destroyed, including routine family and business correspondence. Since this rule applied to most medieval written material, great quantities of records were st...