![]()

Guidance: What It Is

BY BRINGING NEGATIVE ATTENTION to children when they “misbehave,” conventional discipline carries the heavy baggage of punishment. We intuitively know the importance of not punishing young children. If we think about it, the children we work with are only months old. A two-year-old has less than thirty-six months of on-the-ground experience. A three-year-old only has thirty-six to forty-seven. A big, honking just-five-year-old has only sixty months, one-eighteenth of the projected life span of many young children today.

Young children are just beginning the complex emotional-social learning process that continues throughout their lives. How complex? Many of us know folks in their seventies who have a hard time expressing strong emotions in nonhurting ways. Young children are just beginning this vital lifelong learning that even senior adults have not always mastered! Being only months old, young children are going to make mistakes in their behavior, sometimes spectacularly, as all beginners do.

Learning from Mistakes

Guidance is teaching for healthy emotional and social development. On a day-to-day basis as conflicts occur, leaders who use guidance teach children to learn from their mistakes rather than punish them for the mistakes they make. Teachers help children learn to solve their problems rather than punish children for having problems they cannot solve. In the guidance approach, leaders first assist children to gain their emotional health in order to be socially responsive and then support their social skills that are needed to build relationships and solve problems cooperatively. For this reason, in a change from my earliest works, I make a practice of referring to “emotional-social” development and not the other way ’round.

Even though it rejects punishment, guidance is authoritative (“possessing recognized or evident authority; clearly accurate or knowledegable” [Merriam-Webster 2020]). No one is to be harmed in the early childhood learning community—child or adult. But in the guidance approach, the professional is firm and friendly—not firm and harsh. There are consequences for when a young child causes a serious conflict. But the consequences are for the adult as well as the child. The adult needs to work on the relationship with the child and use communication practices that calm and teach, not punish. The consequence for the child is to learn another way.

Using conventional discipline, a teacher puts fifty-four-month-old Marcus on a time-out chair for taking a trike from Darian, a younger child. (Darian objected loudly and was forced off.) In the time-out, Marcus is not thinking, “I am going to be a better child because the teacher has temporarily expelled me from the group. Next time I will not take things from others. I will patiently wait my turn—and am not thinking at all about getting back at Darian!” Really, Marcus feels embarrassed, even humiliated, upset, and angry—far from the emotional set needed to figure out what happened and what would be a better response in the future. (Thought: Isn’t the adult here contributing to a bully-victim dynamic?)

Whatever the noble linguistic roots of the term discipline, to discipline a child has come to mean “to punish.” Again, punishment makes it harder for children to learn the very emotional-social capacities we want them to learn, such as waiting for a turn on the trike or using the trike together.

In contrast a leader who uses guidance intervenes without causing embarrassment; helps one or both children calm down; talks with the two about what happened; guides them toward another way to handle a similar conflict in the future; and facilitates (not forces) reconciliation. In the process, the leader conveys to the children that they are both worthy members of the group, they can learn a new way, and they can get along (avoiding a bully-victim dynamic).

The leader makes the time for this mediation because by modeling as well as teaching friendliness during conflict, the whole group is learning. Firm, friendly, and intelligent teaching is what I mean by moving past discipline to guidance—proactively teaching children that they are worthy individuals, belong in the group, and can learn to manage their strong emotions.

Reframing the Conventional Wisdom about Discipline

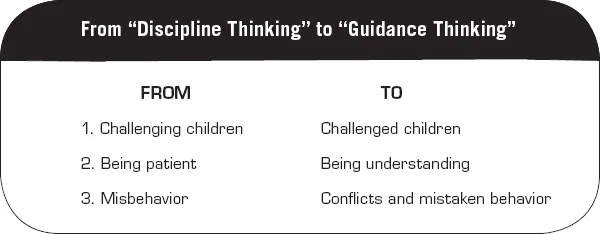

In moving to guidance, the EC leader does well to look at three concepts associated with conventional discipline. The following table illustrates the reframing of discipline thinking to guidance thinking. Discussion of each idea shift follows.

1. From “Challenging” Children to “Challenged” Children

A beautiful benefit of brain research that has been conducted over the last thirty years is that it is helping us understand the behavior of young children like never before. Years ago if a child caused frequent and extreme conflicts, the conventional wisdom was that this was a “bad kid,” or at least a “challenging child with a bad home life.” Those who believed in the positive potential of all children didn’t have a lot more than general long-term studies to back their guidance efforts. Now, with the findings of neuroscience, there is more.

The matter comes down not to the character of the child—and whether the child is labeled “challenging”—but to the amount of stress the child is living with. At the time of birth, the brain’s defense system, mediated by the amygdala, is already functioning. Generating emotional reactions to incoming perceptions, the amygdala is a key part of the limbic system, located within the temporal lobes in the lower area of the brain. If the amygdala senses a threat, it orders up stress-related hormones that slosh around in the brain (hypo-scientific term here), causing the individual to show survival behaviors for self-protection.

Human survival behaviors are well known—fighting (aggression), freezing, or fleeing. In this connection, babies who cry out of discomfort are showing the survival behavior of aggression. No matter what the circumstances, the persons present, or the time, babies are going to let the world know when they feel the stress of discomfort. And so it should be for their survival. In the context of the EC learning community, however, survival behaviors are often counterproductive. They are mistaken efforts at self-survival that other members of the community find challenging.

By around age three in the frontal lobes of the cortex in the upper brain, the child’s conscious thinking and response systems have begun to develop. “Executive function” is the term for the mechanism that mediates intentional thinking and doing. Executive function integrates the processes of recall, idea formation, task persistence, and problem-solving.

In the young child, developing language and social awareness play a crucial role in the processes mediated by executive function. This understanding provides a useful explanation for why preschoolers bite less frequently than toddlers. Three-year-olds are gaining language skills and social awareness that toddlers have not yet developed. For me, two notes about executive function are essential (the first is political; skip to second note if you’d like):

1. Executive function begins to develop at around age three, but it does not reach full and mature operation until individuals are in their twenties. Think of the differences in the behaviors of teenagers and twentysomethings to nail down this understanding. In my view, this is why teens should not be able to purchase guns until they are twenty-one—the current legal age for alcohol and tobacco.

2. In young children’s brains, the amygdala system is more fully formed than the executive function system. If unmanageable stress enters a child’s life, amygdala functions override beginning executive functions. Being totally dependent on others for security, young children are particularly vulnerable to strong amygdala reactions and survival behaviors. Toxic (unmanageable) stress can result from a single adverse event or a series of events in a young child’s life that the child perceives as threatening. Insecure relationships with primary family members are a widespread cause of this plaguing stress in young children, though not the only cause (see Gartrell, 2017).

Brain research has put a new focus on the role of stress in people’s lives. The term toxic stress has come to explain stress that is beyond the individual’s ability to manage. For me, however, this term can set off an either/or shortcut reaction in others. Either you have toxic stress or you don’t. Unmanageable stress seems more nuanced, and I often use this term instead of toxic stress. Unmanageable stress refers to a level of stress that impedes healthy problem-solving and creative behavior.

Unmanageable stress begins where “healthy stress” ends. Healthy stress in young children, what I like to call “intrigue,” is when amygdala and executive functions are integrated in activity around problem-solving and the resolution of cognitive dissonance (things that don’t appear to fit together). For example, a child who relishes putting together a new puzzle is showing healthy stress. A child who doesn’t solve the new puzzle but stacks the pieces in the middle of the board and says, “This is a castle in a lake,” is also showing healthy stress—unless this child is told, “You are not doing it right.” A child who can’t do the puzzle and sweeps the pieces on the floor is experiencing unmanageable stress—likely not just in that moment.

Unmanageable stress felt at different levels results in survival behaviors shown to different degrees. Outside of the early childhood community, survival behaviors might help children in traumatic situations. Within the community, leaders who use guidance recognize that children who display especially the survival behavior of aggression are not “bad” children. They are showing mistaken survival behaviors and are really asking for help. Children show challenging survival behavior in encouraging EC communities because it is a safe place in their lives. They know they won’t be punished for acting out with survival behaviors, even if the behaviors are mistaken.

Understanding the link between unmanageable stress and serious conflicts is important. As children become older, if they are not helped to manage toxic stress, the amygdala system becomes overdeveloped at the expense of underdevelopment of executive function. Think long-term learning difficulties here and chronic oversensitivity to everyday events that seem threatening. Leaders work hard with young children to build relationships that make stress manageable while brains and personalities are still “plastic” (pliant and rapidly forming). Professionals leverage their efforts at guidance leadership by working together with family members and fellow staff. They understand that challenging behaviors happen because children are challenged.

2. Patience or Understanding?

Nancy Weber first brought this idea to light in 1987. Her “food for thought” article in Young Children continues to be a topic of interest on the internet.

Weber’s idea is that the importance of patience is overplayed in EC education, and the importance of understanding is underplayed. People often say to EC professionals that they “must be so patient,” when they might not see themselves as patient at all. In making her case, Weber cites a definition of “patience,” very close to that of a Microsoft search of “patience definition” today: “the capacity to withstand frustration, trouble, or suffering without getting angry or upset.”

With Weber’s permission, “Patience or Understanding” served as the first chapter of my 2004 book, The Power of Guidance. Out of respect for Weber’s contribution, I paraphrase this idea shift in her terms—she said it so well.

Weber’s contention is that in Western culture, “patience” is often accompanied by an unintended passive-aggressive state of mind. She means that EC professionals, being human, at some point run out of patience and act out. A leader might “lose it” when any of the following occurs:

• A child acts out one too many times.

• Children “once again” show restlessness during large group.

• A parent misses a second conference and doesn’t seem to care.

• A staff member repeats an inappropriate practice previously discussed with a supervisor.

The big switch is this: instead of relying on patience with the danger of its running out, EC leaders strive to understand. Patience might or might not then be a response, but holding back after reflection is a mindful choice and not a stoic reaction. The basic point of her article is that we are unlikely to run out of understanding. To illustrate, consider that an openness to understanding helps professionals be proactive so they investigate and perhaps learn one of the following:

• The child who acts out is arriving at Head Start on a middle school bus and every morning is getting teased.

• Teacher expectations at large-group time are just not developmentally appropriate for these children at this time.

• The parent is on her own, has three young children, and works long hours as a waitress. The family often crashes at Gramma’s.

• The staff person is dealing with a family member at home who has a drug problem.

Even when the professional’s learning is not this conclusive, the effort to understand tends to change the dynamics of conflict situations. The leader is more likely to remain engaged with people and events and not as likely to feel alienated from the situation—and lose patience.

3. Not Misbehavior, but Conflicts and Mistaken Behavior

If the trappings of conventional discipline rattle around in our heads, we tend to think of the conflicts that young children cause as misbehavior. The problem is that “misbehavior” carries the same moralistic cultural baggage as “discipline.” If we interpret a conflict that a child causes as misbehavior, it is simply too easy to regard the matter in moralistic terms. Misbehavior is bad behavior, and what kind of kids show bad behavior? Kids who are bad, rowdy, wild, bullies, or from bad families (i.e., challenging). It is an easy slide to view child...