![]()

Part 1

Anatolian Landscapes, History, Gender, and Trauma

![]()

1 Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

The Enfolding–Unfolding Aesthetics of Confronting the Past in Turkey

Özgün Eylül İşcen

Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once Upon a Time in Anatolia [Bir Zamanlar Anadolu’da]1 is a film about a murder investigation that takes place in an Anatolian town of Turkey.2 The small-town bureaucrats – the regional prosecutor, the police commissioner and his deputy, the town’s doctor, drivers, and soldiers – and the suspects, who are said to have confessed, look for a buried corpse. They drive around the countryside all night long to find the buried body in one of the fields outside the town. One of the suspects, Kenan (Fırat Tanış), has killed the victim in a fight after Kenan has confessed that he is having an affair with the victim’s wife and is the actual father of his child (which unfolds as a possible truth later in the film). Kenan cannot remember the exact place where they have buried the corpse, as he claims that he was drunk that night, and the other suspect is Kenan’s mentally challenged brother. Nobody knows whether Kenan cannot or will not identify the place, which is supposed to be located near a fountain not far from a round tree standing a little further from the road.

As the night spent in the dark steppes and rock cliffs of Anatolia with rain, wind, and a full moon prolongs, the viewer witnesses the unfolding of these men’s inner worlds, personal dilemmas, and secrets, as well as hierarchical and competitive relations. As Senem Aytaç underlines, the actual truth quest of the film is not concerned with illuminating the murder, but unfolding the power struggles and social hierarchies that deeply characterize Turkish provincial life (28–31). Moreover, the tropes of trauma, scapegoating, and shame keep coming to the surface around both the murder case and the personal stories of these men. As the night continues, secrets and weaknesses of these different ranked provincial men come to light, despite all their masculine efforts to hide or pretend otherwise, whether in the form of a self-victimization or humiliation of each other. Even though truths and images keep returning to a state of latency, they still nourish the Anatolian setting lying over thick layers of history and make it potentially radioactive, with the prospect of a future unfolding.

From the very first frame, Once Upon a Time in Anatolia sets its interest in tackling the enigmatic relationship between truth and visibility that complicates the question of what can be known. The opening scene, even before the credits, raises this very problem of visibility. The camera tracks toward a dirty window, through which the viewer gradually sees three men eating and drinking, but cannot hear them more than a murmur. After the credits interrupt the flow with a black screen, a new scene starts with a wide-angle shot of empty hills in the twilight, where car headlights emerge at distance, like a series of little fireballs, and drive slowly over the curved roads closer to the camera. Only when the police commissioner comes out from the car with the handcuffed man and brings him next to the fountain, the viewer gets the idea of the film’s plot of searching for a buried body. The film neither offers an image of murder nor clarifies details about the murderer. Our very first view, which might enlighten the question of murder, is obscured. As the journey from one fountain to another continues along with the murder inquiry throughout the night, the truths of the murder and personal stories become even more convoluted.

Throughout the film, the position of the victim, guilty, and witness keeps changing, and thus, the film does not offer any strong identification with the characters or any secure ethical stance for the viewer. The film does not unmask the secrets by exposing the falsity of the stories. Rather, the film brings the viewer closer to the complexity of memory and reality by showing how those secrets underscore the wounds and denials of these characters and, therefore, reveal more about the characters and the very conditions of their denials. Unlike a secret, which is unveiled in the process of being communicated, “enigma draws its strength from the questioning tension that it arouses” (Perniola 10). The secret is based on a simplistic conception of reality and on the subjective will to hide its evidence. Enigma, however, comes into play when the secret slips from the control of its owner, since reality assumes a shape that is more complex, many-sided, and contradictory than was previously imagined. According to Mario Perniola, enigma is not an obstacle on the quest for truth, but an essential aspect of it, especially in a society in which nobody any longer knows what is really happening, and in which a state of organized uncertainty reigns (11).

This chapter argues that the tropes of trauma, scapegoating, and shame that organize the film’s enigmatic narrative and visual style contribute to the viewer’s sense of ambiguity and uneasiness by mirroring the problem of collective memory in Turkey. As Mithat Sancar puts it, the problem of collective memory in Turkey refers to the country’s inability or unwillingness to confront and come to terms with the accumulated violence, oppression, and injustice it has been carrying from its past (24). The period starting with the final years of the Ottoman Empire, and continuing with the foundation of the Turkish Republic3 involved traumatic events during which ethnic and religious minorities were massacred, deported, and encouraged to migrate in the name of establishing a unified national identity (Özyürek 11). In its short period of life, Turkey suffered three military coups, followed by various configurations of violence and repression: 27 May 1960, 12 March 1971, and 12 September 1980.4 These events generated long-lasting trauma and instability in Turkey with no time for mourning, and very limited channels for coming into terms with the past. As Mithat Sancar argues:

In Once upon a Time in Anatolia, Ceylan does not only rely on narrative tropes of trauma, but also makes the viewer feel the intensity of repression and denial through formal, stylistic qualities, such as lighting, close-ups of faces, and long takes of the Anatolian landscape. Particularly, I argue that the Anatolian landscape becomes an active participant in the constitution of the filmic style and its emotional world through its material and historical conditions. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia shows that the past may be buried, but is always ready to spill over and intervene into the present moment. With the touch of Ceylan, the violently repressed histories of Turkey, enfolded in the land and people of Anatolia, continue to unfold in enigmatic ways. The film is not interested in offering a resolution, and thus it makes the viewer feel uneasy while suggesting an upcoming confrontation with the dark sheets of the past.

This chapter aims at rethinking the narrative and formal qualities of Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, in relation to the problem of collective memory in Turkey. Both the main theme of murder and the characters’ personal stories speak to the struggle of confronting one’s past and seeking the truth. The characters’ ceaseless effort for finding the buried corpse becomes a metaphor for such a struggle. At the same time, the formal qualities of the images trigger the question of what can be seen and known, whether of the past or reality itself. In this regard, I draw upon the theory of enfolding–unfolding aesthetics as proposed by Laura U. Marks, and Gilles Deleuze’s conception of Time-Image at the intersection of the sheets of past and the peaks of present. This inquiry offers a reflection on the stylistic strategies and political implications of enfolding–unfolding aesthetics, especially regarding the problem of collective memory in countries that struggle with confronting their violent past – where secrets turn into enigmas.

The Anatolian Setting: A Landscape of Turkey in Crisis

Watching Once Upon a Time in Anatolia is overwhelming as living in that geography can easily become so. All the efforts that the characters put in order to avoid confronting their trauma, guilt or shame, from idle talking to constant grumbling, become visible to the viewer as a reflection on their similar efforts. While describing his experience of watching the film at a theater, Şükrü Argın underscores the moments, in which the audience laughs together at a scene; for instance, when the characters keep teasing one another, getting into a fight over a mundane issue, or collecting fruits from the trees/fields in the middle of a murder investigation (19). By laughing at/with the characters, despite all the roughness of what is witnessed, the viewer is forced to realize how those idle talks and jokes act like a protective shield between the characters and the current event, corpse, and autopsy. Ceylan seems to be interested in making the viewer feel uneasy at the turn of each laugh and reminding that this story is also their own (22).

The laugh that the audience keeps sharing throughout the film, however, is not more innocent than the blood spread at the face of the doctor, Cemal (Muhammet Uzuner), in the autopsy scene toward the end of the film (Argın 19). During the autopsy scene, the autopsy technician who performs the autopsy finds pieces of earth in the lungs of the victim and, thus, realizes that the victim has been buried while he was still alive. Since burying one alive is a more violent act, it would warrant a longer prison sentence, and the doctor chooses not to mention it in the official report. The doctor’s motivation is not given in the film. His encountering the wife and the young son of the victim at the hospital before the autopsy, who might be also the son of the murderer, could play a role in the doctor’s decision. After he covers up the truth about the cause of death, a piece of blood splashes onto his face. The splash stays on his cheek, while he is watching the wife and son of the victim walking away from the hospital over his window. Actually, after the splash, the technician tells the doctor to stay away from the autopsy table to “avoid getting dirty.” Until this scene, the doctor seems to be the character that the viewer can identify with or rely on. He is the man of rationality and objectivity, the man of the city who is a foreigner to the rough rules of the provincial life. Therefore, this scene marks his partaking in the rules of the game and leaves the viewer unguided about whom to believe or side with. It is not a coincidence that the doctor is the only character who looks into the camera in the film, following the reverse shot of him looking at the mirror in a scene prior to the one of the autopsy.

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia tells the stories of buried murders, unheard complaints, and postponed autopsies of Turkey. With idle talking or silences, the characters maneuver around those stories. This film is one of the most talkative films by Ceylan, even though most of the talking happens to fill the gaps of truth, or in the form of complaining about one another behind their backs. The characters fail not only to have a genuine conversation, but also to look at one another in the eye (Argın 23–24). As Murat Paker puts it, a confrontation with a past or current event requires two people, who claim opposite things regarding the event, come face to face with one another (“Sonsöz” 380). The motivation behind looking at each other’s eyes is to understand who is telling the truth and who is lying and to create a space for empathy and conscience. In Turkish, one says, “gözlerime/yüzüme bak [look at my eyes/face],” to determine if the suspected other is lying or not. Paker’s point recalls Ceylan’s interest in the facial and bodily gestures that the truth gathers around, while it is hidden, exposed, or unsettled with.

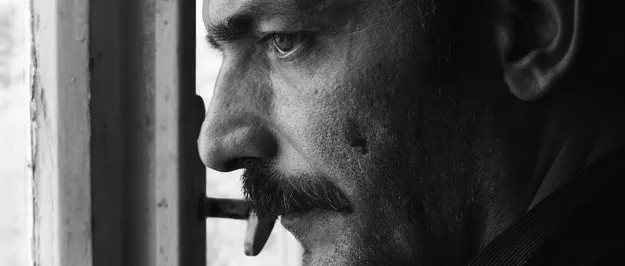

Figure 1.1 Still from Once Upon a Time in Anatolia.

Ceylan does not invest in dialogues for their capacity for revealing the truth, but insists on the close-ups of faces and eyes, like the wavering light over the wounds of the prosecutor’s face. The conversation between the prosecutor Nusret (Taner Birsel) and the doctor seems genuine at first; however, the film eventually gives the impression that the prosecutor tells the story of his wife’s suicide, as if it were about his friend’s wife’s mysterious death. In the prosecutor’s version of the story, the wife knew the exact date she would die while she was pregnant, and dropped dead after giving birth on that day for no apparent reason. As a man of medicine, the doctor is the only one who can reveal the truth about the death of the wife, a truth that the prosecutor does not want to admit to himself. The prosecutor even actively escapes the truth, by the fact that he avoided having an autopsy performed on his wife, which would clarify it all.

Only before the autopsy scene, the prosecutor reveals that the woman caught her husband with another woman. She forgave him and they did not mention it again. Even though the doctor warns him about other possible meanings of that silence, the prosecutor claims that the man has done nothing wrong and been forgiven....