![]()

1. DRESSED FOR THE OCCASION. CLOTHES AND CONTEXT IN THE ROMAN ARMY

Michael Alexander Speidel

Modern images and reconstructions of the Roman soldier’s appearance nearly always show a fully- armed, often grim-looking combatant, wearing helmet and armour and sporting several weapons. Such images have heavily influenced the way in which we think of Roman soldiers and the Roman army. There is, of course, some logic to these representations, as they immediately reveal the person’s military profession. It is therefore not surprising to find them in use already by the Roman soldiers themselves.

Images of fully armed soldiers of all ranks can be found in large numbers on gravestones throughout the first three centuries AD (Fig. 1.1). They supplement the information given by the inscription and add splendour to the tombstone and the memory of the deceased soldier. The context, however, is that of a monument, designed to impress the onlooker. As the design of gravestones was based on choices made by individual soldiers these monuments can therefore serve as a guide for the importance Roman soldiers attributed to the composition of their last appearance as well as for the meaning conveyed by such images.

Figure 1.1. Fully armed legionary. 1st c. AD (Wiesbaden).

Several obvious reasons may have led soldiers to choose representations of themselves in full battle gear for their gravestones: Such images would show the deceased to have been a professional soldier with the Roman army, which means that during his lifetime he had been an agent of the emperor, representing Roman imperial power, and therefore a person to respect (if not to fear). Such images would also serve to impress the onlooker by the wealth and success the soldier had achieved during his time on earth: a splendid appearance in shining armour, perhaps further embellished by military decorations betraying his bravery on the battlefield.1 Those who had received promotions could show the insignia of higher ranks, revealing their proven capability to be a leader, trusted by their superiors and respected by their comrades, devoted to duty and ready to fight for the Roman empire.

Surprisingly perhaps, the actual act of killing the enemy was, on the whole, rather unpopular on soldiers’ gravestones, as it occurs on only one particular type of image, which shows an armed Roman horseman riding down a barbarian and aiming his spear at the fallen enemy while looking straight ahead (Fig 1.3).2 This image was chosen primarily (yet not exclusively) by Roman cavalrymen on the northern frontiers. It has recently been recognized, however, that in several cases the enemy, a (half-) naked Germanic warrior, is not necessarily fallen, but has willingly dived beneath the horse to stab it from below.3 That, of course, makes the fight more equal. Perhaps the original meaning of the scene was to show the Roman horseman and his mount jumping over the Germanic horse- stabber rather than riding him down. If correct, jumping, throwing a spear at the enemy underhoof and concentrating on the foe ahead all at the same time is an image which would serve to prove the impressive skills and the courage of the deceased. However, this image also came in less cruel versions, either without the barbarian, or with military decorations or (since the late second century) a wild boar in his stead (thereby turning the picture into a hunting scene). Hence, the emphasis of the message was not so much focussed on the soldier’s professionalism at killing but much rather highlighted his heroic and victorious bravery as well as his extraordinary skills as a horseman.4 That was what he wanted to be remembered for.

The same message as with full portraits of the armour-clad soldiers could also be transmitted in a less martial setting by displaying only selected items of military equipment or military decorations (Fig. 1.4).5 Again, this type of image was not restricted to any particular rank within the Roman army or any particular frontier. It is revealing that even images of the emperor could make use of the same set of symbols when they were to emphasize the ruler’s role as commander-in-chief of the Roman army.6 Images of the emperor in military dress or in armour were designed to promote the understanding, that the vigilant ruler successfully used his military power to secure peace and prosperity for the Roman Empire. Of course, such images were not carried by gravestones but by different media, such as statues, reliefs or coins. Their messages, however, were much the same: Armour and weapons were used as symbolic representations in public displays of a successful, responsible, and heroic military service for Rome and empire-wide peace by all members of the Roman army, including equestrian and senatorial officers and generals as well as emperors.7

Figure 1.2. Soldier and his wife in civilian clothes. 3rd c. AD (Augsburg).

A second style of images on gravestones, which were also produced throughout the first three centuries AD, shows soldiers without armour, wearing only a belted tunic and a cloak (Fig. 1.2). Weapons and other military attributes could also be added. The character of these images is obviously less martial in its general appearance and was certainly intended to preserve a memory of the soldier in a context which was not battle or war. It was with great disgust that Tacitus described Roman soldiers without helmet and body armour in the cities of Syria as sleek money-making traders.8Tacitus and other Roman aristocrats may have scorned the peaceful appearance of the army in the provinces,9 many soldiers, however, consciously chose such images for their gravestones. It is therefore certainly revealing, that the images of soldiers wearing only belted tunics and cloaks became ever more popular and finally, by the third century, clearly outnumbered the representations in full armour.10 This must surely be taken as a sign of the soldiers’ increasing will to be remembered not so much as battle-hardened warriors but rather as fellow citizens, or even, when shown with wife and children,11 as fathers and family-men.

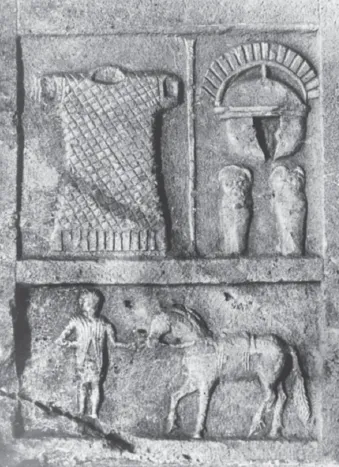

Figure 1.3. Auxiliary horseman and horse-stabber. 1st c. AD (Glouchester).

Figure 1.4. Legionary centurions military equipment, servant and horse. 1st. c. AD (Carnuntum)

If soldiers more and more preferred not to be seen, on their gravestones, as heavily armoured, battle-ready fighters, they would still regularly choose to show the insignia of their profession and their power, and thereby remind us of their former importance in society. On principle, these insignia included belt and cape. By contrast, the soldiers’ servants are never shown with swords, although they are known to have joined the soldiers in training and battle.12 Soldiers with higher ranks would also not shy away from showing their badges of office. Such details added information and therefore played an important role in the composition of the images of soldiers. Hence, under-officers and officers, dressed in tunics and cloaks, could be shown holding a set of writing tablets or a scroll in one hand, and either lanceae,13 standards,14 a fustisp,15 a hastile,16 or a vitis17 etc. in the other. The tablets were surely meant to portray the soldiers’ writing-skills and therefore appear to indicate that at some stage in their career they had held positions involving administrative tasks.18 Lanceae and standards, however, were carried in battle and during manoeuvers, the fustis was a nightstick which was used as a police weapon, the long hastile was the typical staff of an optio, with which he was to keep discipline and order amongst the soldiers in the battle lines, whereas the vitis, a vine cane, was the badge of office of centurions and evocati and their sign of authority with which they could beat and punish insubordinate soldiers.19 In some instances such combinations of writing-material and different types of staffs could serve to illustrate the soldier’s rank (signifer, beneficiarius, optio, etc.) by showing typical items of their office. Obviously, however, both instruments were never used at the same time. Such cases must therefore serve as a warning, not to interpret these images as snapshots of a former reality. They were not composed as guide...