![]()

PART ONE

POWER

![]()

ONE

NO WOOD, NO KINGDOM

A cold, gray day, and heavy snow billowing. Saturday, 28 December 1598, the forty-first year of the reign of Elizabeth Tudor, Queen of England and Ireland. On the edge of London Town, in the precinct of Holywell, workmen gather in the yard before the old Theatre, snow on their beards, stamping their boots and clapping their gloved hands to keep warm. Hailing each other with ale-warmed breath: work to do, and that quickly, shillings to earn even in holiday time. Wood was scarce in London, the forests that ringed the city stripped bare. The workmen had been hired to tear down the Theatre, the first of its kind, and move the salvaged framing to master carpenter Peter Street’s Thames-side warehouse, hard by Bridewell Stairs. Steal a whole building, someone winked, right out from under the absent landlord’s nose, though who rightly owned the Theatre would need years of litigation to decide.1 The Burbage brothers, William Shakespeare’s partners in the theater business, believed they did. They’d built it, in 1576. Let the landlord keep his land. They would dismantle their playhouse and raise it elsewhere.

Giles Allen, the landlord, away at his country house in Essex, would tell the court that men with weapons bullied aside the servants he sent with a power of attorney to stop them. With all the shouting, a crowd gathered. The Burbage brothers were there that day. So was Shakespeare. Moving the playhouse was urgent if their acting company would have a stage to perform on. Allen was threatening to pull it down himself and salvage the timbers to build tenements, as apartments were called in Shakespeare’s day.

The Burbages’ workmen dismantled the wooden building and carted the framing away. Two days earlier, the company had played before the Queen at Whitehall Palace. It was scheduled to play there again on New Year’s night. The Theatre came down between the two performances.

It went up again in Spring 1599 across the Thames in bawdy Southwark, enlarged and renamed the Globe, a twenty-sided polygon three stories high and a hundred feet across, with a thatched ring of roof open to the sky above a wide yard. Peter Street probably cut the new timber for the enlargement in a forest near Windsor, west of London, lopped and topped and barked and shaped it there to avoid the cost of barging whole trees down the Thames. A Swiss tourist, Thomas Platter, attended a production of Julius Caesar in the new Globe on the afternoon of 21 September 1599, so it was up and running by then. He thought the play “quite aptly performed.”2

Elizabethan England was a country built of wood. “The greatest part of our building in the cities and good towns of England,” the Elizabethan observer William Harrison reported in 1577, “consisteth only of timber.”3 Even the country’s implements, its plows and hoes, were wooden, if iron edged. London was a wooden city, peak-roofed and half-timbered, heating itself with firewood burned on stone hearths called reredos raised in the middle of rooms, the sweet wood smoke drifting through the house and out the windows.

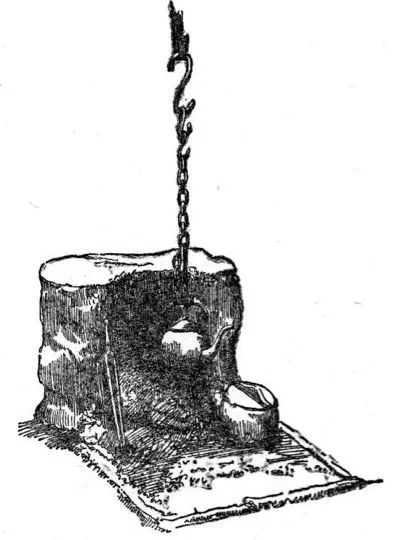

A reredos, with hook above for hanging a kettle.

But wood was growing dear, its price increasing as London’s population increased and woodcutters carted firewood into the city from farther and farther afield. Parliament provided a limited remedy in 1581: a law prohibiting the production of charcoal for iron smelting within fourteen miles of London, to reserve the nearby trees for domestic fuel. Even so, the cost of firewood delivered to the city more than doubled between 1500 and 1592, consistent with the burgeoning population, which quadrupled between 1500 and 1600, from 50,000 to 200,000.4 (England’s entire population increased across that century from 3.25 million to 4.07 million.5)

Some economists today question if England was running out of wood. The Burbages and their company moved the Theatre’s framing not only to save wood but also to save time and money putting up their new, enlarged Globe bankside. And wood, after all, is a renewable resource. Yet many seventeenth- and eighteenth-century government officials, parliamentarians, and private observers feared a wood shortage, especially of large oak trees suitable for ships’ masts.

Warships were as valuable to national security in those days as aircraft carriers are today. About 2,500 large oak trees went into an average English ship of the line.6 It was a beautiful wooden fighting machine, massive and solid, fifty feet wide and two hundred feet long. Two rows of cannon mounted on wooden trucks pierced its bulging yellow sides. Its decks were painted dull red to veil the blood that flowed in battle.7 It carried its sails on no fewer than twenty-three masts, yards, and spars, from the forty-yard-long, eighteen-ton mainmast to the little fore topgallant-yard, a light seven-yard stick.8 Patriots said the Royal Navy was England’s “wooden walls,” protecting it from invasion. The Admiralty built and maintained about one hundred ships of the line as well as several hundred smaller ships and boats. Battle and shipworms ravaged them; they needed replacing every decade or two.

But the great mast trees took 80 to 120 years to grow to sufficient diameter. A landowner who planted an acorn could hope his grandchildren or great-grandchildren might harvest it for profit—if the intervening generations could wait so long. Many could not; many did not. Selling timber was an easy means to raise cash; landowners from the king on down took advantage of the opportunity whenever their purses emptied. Wood, the dilettante second Earl of Carnarvon told a friend of the diarist Samuel Pepys, was “an excrescence of the earth provided by God for the payment of debts.”9

Crooked hedgerow timbers—“compass timbers,” the Admiralty called them—were as important to ship construction as the straight forest timbers needed for the masts. These great bent oaks supplied curved and branched single pieces for the keel, the stern-post, and the ribs of the ship’s hull. They were always scarce and priced accordingly, but with the enclosure movement of late-medieval England—the privatization and consolidation of communal fields into sheep pasture to benefit the manorial lords—most of the compass trees were cut down. Finding the right piece for a ship could take years.

The Ark Royal, built for Sir Walter Raleigh in 1587, carried fifty-five guns on two gun decks. In 1588 she chased the Spanish Armada into the North Sea.

The Royal Navy was not the only enterprise consuming the forests of England. By the 1630s, the country supported some three hundred iron-smelting operations, which burned three hundred thousand loads of wood annually to make charcoal, each load counting as a large tree.10 Building and maintaining the more numerous ships of British commerce required three times as much oak as did navy shipping.

Timber, oak in particular, competed with grain for arable land. Great trees needed deep, rich soil, but it was more profitable to farm such land for feed. A Suffolk County official named Thomas Preston associated mighty forests with primitive conditions, “the past age” when the kingdom possessed “a great plenty of oak.” The diminution of oak measured the kingdom’s improvement, he argued, “a thousand times more valuable than any timber can ever be.” Preston hoped the diminution would continue: “While we are forced to feed our people with foreign wheat, and our horses with foreign oats, can raising oak be an object? . . . The scarcity of timber ought never to be regretted, for it is a certain proof of national improvement; and for Royal navies, countries yet barbarous are the right and only proper nurseries.”11

Those barbarous countries included North America, especially New England, where the colonists had just begun to harvest the primeval forest. There, from 1650 onward, the Admiralty sought the strong “single stick” masts its warships required, forty yards long and three to four feet in diameter. The colonists competed for the wood, however. The first American sawmill began operations in 1663 on the Salmon Falls River in New Hampshire, long before the English advanced from sawing board by hand to using water power. By 1747, there were 90 such water-powered mills along the Salmon Falls and the Piscataqua, with 130 teams of oxen working hauling logs. Among them, they cut about six million board feet of timber annually for sale in Boston, the West Indies, and beyond. England got her share. The eighteenth-century historian Daniel Neal, in his The History of New-England, noted that the Piscataqua was “the principal place of trade for masts of any of the king’s dominions.”12

Unfortunately for the Royal Navy, America’s successful revolution three decades later cut off its supply of American white pine. It had to return to its earlier expedient of using “made masts”: weaker composite masts of multiple trees strapped together around a central spindle.

Besides making charcoal to smelt iron, the English cut down timber to build houses, barns, and fences; to produce glass and refine lead; to build bridges, docks, locks, canal boats, and forts; and to make beer and cider barrels. More than one of these uses consumed as much wood as the navy. Even royalty was guilty of misusing the royal forests, while Parliament stood by. “The final failure of the woodlands,” a historian concludes, “was the result of constant neglect and abuse.”13

The Jacobean agriculturalist Arthur Standish was concerned less with the needs of the Royal Navy and more with what he called “the general destruction and waste of wood” when he published The Commons Complaint under King James I’s endorsement in 1611, but he included “timber . . . for navigation” among the shortages that he foresaw. Paraphrasing one of the king’s speeches before Parliament in his stark summary of the consequences, Standish concluded: “And so it may be conceived, no wood, no kingdom.”14

A cheaper alternative was burning coal—sea coal or pit coal, the Elizabethans called it to distinguish it from charcoal. (A coal was originally any burning ember, thus char-coal for charred wood, and sea coal or pit coal for the fossil fuel, depending on whether it outcropped on the headlands above the beaches or was dug from the ground.) Harrison, in his 1577 contribution to the Elizabethan anthology Holinshed’s Chronicles, had found the English Midlands already in transition to the fossil fuel: “Of coal-mines, we have such plenty in the north and western parts of our island as may suffice for all the realm of England.”15 Coal had served blacksmiths for hundreds of years. Soap boilers used it; so did lime burners, who roasted limestone in kilns to make quicklime for plaster; so did salt boilers, who boiled down seawater in open iron pans, a tedious process prodigal of fuel, to make salt for food preservation in the centuries before refrigeration.

But the acrid smoke and sulfurous stench of the Midlands’s coal had not encouraged its domestic use in houses devoid of chimneys where meat was roasted over open fires. “The nice dames of London,” as a chronicler called them, were unwilling even to enter such houses. In 1578 Elizabeth I herself objected to the stink of coal smoke blowing into Westminster Palace from a nearby brewery and sent at least one brewer to prison that year for his effrontery.16 A chastened Company of Brewers offered to burn only wood near the palace.

Like nuclear power in the twentieth century, but justifiably, coal in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was feared to be toxic, tainted by its origins, diabolic: “poisonous when burnt in dwellings,” a historian summarizes Elizabethan prejudices, “and . . . especially injurious to the human complexion. All sorts of diseases were attributed to its use.”17 The black stone found layered underground that burned like the stinking fires of hell—the Devil’s very excrement, preachers ranted—suffered as well from its association with mining, an industry that poets and clergy had long condemned. Geoffrey Chaucer, in his short poem “The Former Age,” written about 1380, set the tone:

But cursed was the time, I dare well say,

That men first did their sweaty business

To grub up metal, lurking in darkness,

And in the rivers first gems sought.

Alas! Then sprung up all the cursedness

Of greed, that first our sorrow brought!18

The German humanist Georgius Agricola, a physician in the mining town of Joachimstal, paraphrased the arguments of mining’s detractors in his 1556 work De re Metallica and quoted Ovid condemning mining in similar terms. The Roman poet, he wrote, had portrayed men as ever descending “ ‘...