![]()

The Tomb of Karakhamun (TT 223)

![]()

Titles of Karakhamun and the Kushite Administration of Thebes

Christopher Naunton1

An individual’s titulary—the words or phrases used to designate an individual, which usually occur before the name in inscriptions2—can provide an indication of his or her social status, roles and responsibilities, and the context in which their work was undertaken. In general they can be divided into groups as follows: ranking titles, vocational titles, and laudatory epithets.

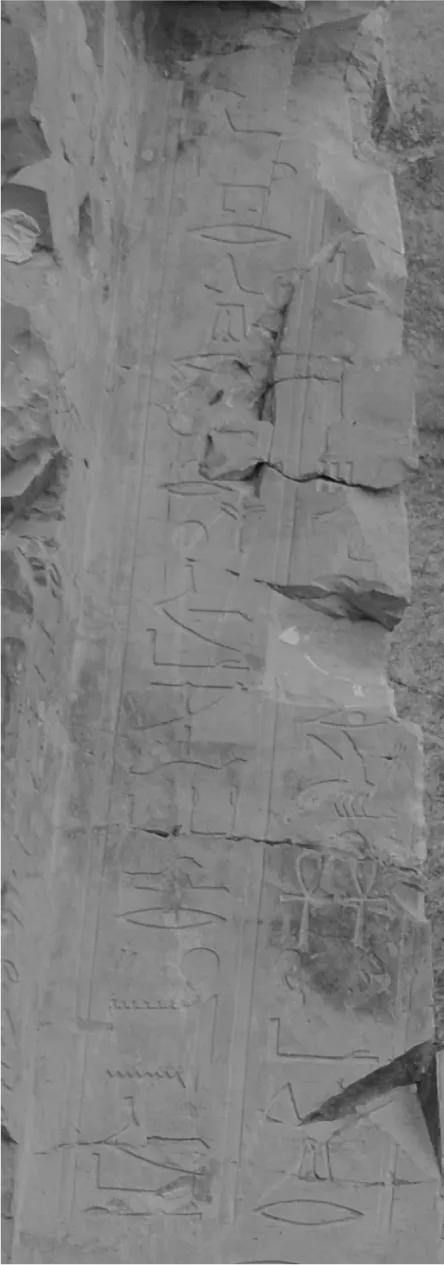

Karakhamun held ten titles—a significant number—including the classic sequence of four ‘ranking’ titles: îry-pꜤt (‘the noble’ or ‘hereditary prince’), ḥꜣty-Ꜥ (‘count’), htmtybíty (‘seal-bearer of the king of lower Egypt’) and smr wꜤty (n mrwt) (‘(beloved) sole companion’)3 (figs. 6.1 and 6.2). By the time of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, these titles had lost what meaning they might originally have had and instead came to signify that the individual held a certain status. The sequence is attested in the titulary of a number of prominent Theban individuals of the time, including the viziers Nespamedu4 and Nespakashuty D,5 the Chief Lector Priest, Padiamunope,6 the chief stewards of the God’s Wife of Amun, Harwa7 and Akhamunru,8 the Kushite Irygadiganen,9 the Fourth Priest of Amun, and governor of Thebes Montuemhat10 and several other members of his family, and the High Priest of Amun, Haremakhet.11

The title rḫ nsw mꜣꜤ (mr.f) (‘the true (beloved) acquaintance of the king’) is similarly taken to denote rank. This title had fallen out of use by the Third Intermediate Period, but reappeared during the Twenty-fifth Dynasty and became common again in the Twenty-sixth,12 perhaps reflecting a resurgence in the importance of relations with the king, and suggesting that Karakhamun was in some way favored by the royal line at this time.

The title írty nsw Ꜥḫwy bíty (‘the eyes and ears of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt’) similarly implies a connection with the king, but seems to have been less common than that of rḫ nsw, being held only by a select few individuals, all of whom held high-ranking offices particularly within the temple of Karnak: the High Priest of Amun Haremakhet,13 the Second Priests of Amun Patjenfy14 and Neshorbehdet,15 the Fourth Priest of Amun, Theban governor, and Overseer of Upper Egypt Montuemhat,16 and the priest of Amun, vizier, and Overseer of Upper Egypt Nespakashuty D.17 The title may simply be an extension of the notion that these individuals were part of the king’s circle, but also suggests that they acted as representatives of the king, perhaps as part of a network of trusted individuals with a brief to monitor the local situation on behalf of the pharaoh. The extent to which this might have involved any practical duties or responsibilities is unclear, however.

Fig. 6.1. Titles of Karakhamun. Offering scene. East wall, First Pillared Hall. Photo Katherine Blakeney, SACP

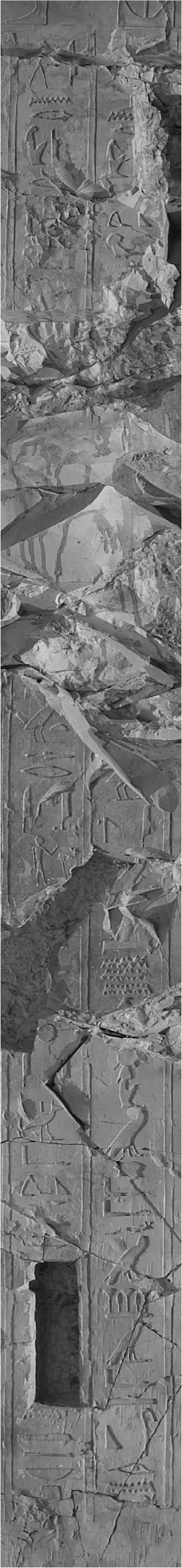

The remaining titles may all be considered ‘laudatory epithets’: wr m íꜤwt.f (‘the one who is great in his offices’), Ꜥꜣ m sꜤḥw.f (‘the one who is great in his dignities’), sr m ḥꜤt rḫyt (‘an official at the head of the people’) and Ꜥk ẖr ḥꜣt pr ẖr pḥ (‘the one who enters first and leaves last’). It has been suggested that the title Ꜥḳ ḥꜣt may be a priestly title and should be translated as ‘first (priest) who enters (the temple),’ or alternatively as two separate titles, Ꜥḳ meaning ‘priest’ and ḥꜣwty, ‘military leader,’ although doubts have been expressed at this interpretation.18 Although the element Ꜥḳ appears alongside secondary elements, such as ‘in Karnak’ and ‘of the house of Amun Akh-menu,’19 and ‘of the Divine Adoratrice of Amun,’20 that would suggest it had religious connotations, it seems also to have been used in other ways,21 and therefore is simply translated as ‘the one who enters,’ which may have meant a variety of different things according to context. It seems more likely that Ꜥḳ ḥꜣt is simply an abbreviated form of the epithet Ꜥḳ ẖr ḥꜣt pr ẖr pḥ.

These epithets do not seem to have been common, but very strikingly all four were also held by the successive chief stewards of the God’s Wife of Amun, Harwa and Akhamunru, both of whom were the owners of monumental rock-cut tombs in the Theban necropolis. However, both these individuals held a number of further titles indicating clearly that they were employed in numerous roles within the institution of the God’s Wife of Amun, which provides an explanation of their status.

Karakhamun’s titles suggest he was an individual of high status, and his tomb, perhaps one of the earliest examples of the resurgence in monumental tomb construction in Thebes under the Kushite pharaohs, might be taken as an indication that he enjoyed considerable wealth at a time when the new line of pharaohs was establishing itself in Thebes. However, his titles in themselves provide little information as to the role and responsibilities he might have held or the context in which he might have been employed, and, therefore, to what or whom he might have owed his status.

Fig. 6.2. Titles of Karakhamun. South wall, First Pillared Hall. Photo Katherine Blakeney, SACP

It is striking that there is no direct reference to any ‘institution,’ such as the temple of Karnak, the estate of Amun, the priesthood of a particular god, or the God’s Wife of Amun, the principal representative of the Kushites in Thebes and the preeminent figure in the cult of Amun.22 The king is referred to, but only in a manner which provides no clear indication that a defined role was involved rather than simply a general connection to the royal court.

A clue to explain his status may lie in his name, rather than his titles. His Kushite name suggests he was of the same ethnicity as the newly established line of pharaohs. His presence in Thebes, apparently in the early part of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, suggests that he may have owed his prominence to a favorable relationship with the new ruling house. There is sufficient evidence to show that a number of ethnic Kushites were introduced to Thebes in the first half of the period.23 The group also includes Karabasken, the Theban governor and Fourth Priest of Amun,24 and owner of tomb TT 391, which is part of the same group of tombs as that of Karakhamun. Karabasken’s appointment to these positions almost certainly interrupted their long-established tenure by Theban families and may be attributed to the intervention of the Kushite pharaohs.25 That Karakhamun bore no titles to show what his role might have been in the Kushite takeover may be due to his having earned favor within the Kushites’ own administrative system, in which no Egyptian titles were relevant. That the Kushites had such a system seems likely and may explain the significant reduction in the number of certain types of titles attested during the Twenty-fifth Dynasty. For example, the prosopographical record suggests that military officials were numerous and prominent in the period prior to the Twenty-fifth Dynasty; however, similar evidence for individual holders of military titles after the conquest of the country by Piye is almost totally lacking. It is possible that the importance of the military declined, but it is more likely that the Kushites replaced the existing system for administering the military with their own, and that the individuals previously in charge of the military, who held certain titles to signify their authority, were replaced by Kushite army officials who chose not to adopt the same titles, either because their systems did not fit those of the previous regime or because their authority was not indicated by titles in the same way.26 Karakhamun may have earned his status outside the existing Egyptian administrative system and thus on arrival in Egypt held no titles that would shed light on his role. He was subsequently given...