eBook - ePub

Islam and Human Rights

Selected Essays of Abdullahi An-Na'im

Abdullahi An-Na'im, edited by Mashood A. Baderin

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 412 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Islam and Human Rights

Selected Essays of Abdullahi An-Na'im

Abdullahi An-Na'im, edited by Mashood A. Baderin

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

The relationship between Islam and human rights forms an important aspect of contemporary international human rights debates. Current international events have made the topic more relevant than ever in international law discourse. Professor Abdullahi An-Na'im is undoubtedly one of the leading international scholars on this subject. He has written extensively on the subject and his works are widely referenced in the literature. His contributions on the subject are however scattered in different academic journals and book chapters. This anthology is designed to bring together his academic contributions on the subject under one cover, for easy access for students and researchers in Islamic law and human rights.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Islam and Human Rights als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Islam and Human Rights von Abdullahi An-Na'im, edited by Mashood A. Baderin im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Law & Law Theory & Practice. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

PART ONE

ISLAM BETWEEN UNIVERSALISM AND SECULARISM

[1]

What Do We Mean by Universal?

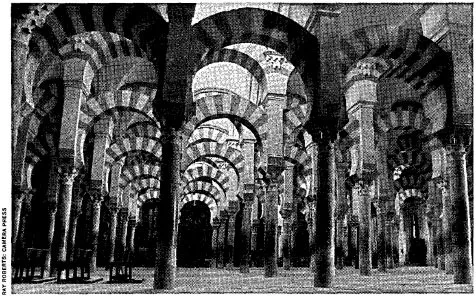

The Mosque in Cόrdoba, Spain: the glory oflslarn in Europe

Any concept of human rights that is to be universally accepted and globally enforced demands equal respect and mutual comprehension between rival cultures

Human rights ought, by definition, to be universal in concept, scope and content as well as in application: a globally accepted set of rights or claims to which all human beings are entitled by virtue of their humanity and without distinction on grounds such as race, gender or religion. Yet there can be no prospect of the universal application of such rights unless there is, at least, substantial agreement on their concept, scope and content.

What is at issue — between those who support a universal concept and those who argue for a relativist approach — is how and by whom these rights are to be defined and articulated. Universality requires global agreement, a consensus between different societies and cultures, not the application of one set of standards derived from the culture and context of a particular society to all other societies. The normative system in one society may not necessarily be appropriate for other societies who need to elaborate their own systems based on their particular cultural context.

Hence the paradox in which the international human rights movement is presently caught: the concept and essential characteristics of currently accepted international standards on ‘universal’ human rights have been primarily conceived, developed and established by the West; they cannot be accepted and implemented globally by the peoples of other parts of the world unless they are seen to be valid and legitimate from their perspectives. If they are to be more widely accepted and implemented, they must be premised on a genuinely universal model rather than the universalisation of a certain culturally specific, ‘Western’, model. To attempt to deny or disguise the dilemma only plays into the hands of those who may wish to manipulate it and undermines the credibility of those who attempt to uphold the contested human rights norms by making them appear to reject what their own constituency sees as obvious and important.

The paradox can only be resolved by first acknowledging the historical facts and then by arguing that although the universal validity of these standards cannot be assumed or taken for granted, they are not necessarily or inherently invalid from the perspective of other cultures. The question of whether and to what extent there is fundamental and irreconcilable difference between a particular international human rights standard and the norms, values and institutions of any other culture, can then be debated internally and across cultures.

All cultures have an element of ambivalence and contestability in the sense that prevailing practices and institutions are open to constant challenge and change. Not only is this essential for the survival of the culture as a whole, it provides a range of debatable options, any one of which may prevail at a particular time. While a particular interpretation or perception of certain cultural norms and institutions may appear to be in fundamental conflict with existing international human rights standards, this does not make it impossible to articulate an alternative interpretation which may begin to resolve the conflict.

If dialogue is to broaden and deepen global consensus it must be undertaken in good faith, with mutual respect for, and sensitivity to, the integrity and fundamental concerns of respective cultures, with an open mind and with the recognition that existing formulations may be changed — or even abolished — in the process. Ideally, participants should feel on an equal footing but, given existing power relations, those in a position to do so might seek ways of redressing the imbalance.

Where the Islamic world is concerned it is important to appreciate the profoundly defensive and reactive mode of internal discourse and cross-cultural exchange. Following the failure of secular liberalism or national socialism in the post-independence era, Muslims are now channelling their frustration and powerlessness into radical and militant Islamic revivalism as an assertion of their right to self-determination. The insistence on one universally valid set of human rights, therefore, risks the sort of confrontation we have seen in the Rushdie affair and forces debate under the worst possible circumstances.

The value and validity of a given concept of human rights is neither necessarily diminished nor validated by the fact that it is historically or geographically specific. It may well be that the ‘democratic way of life’ which presupposes the existence and acceptance of a certain concept of individual human rights is superior to other forms of political life. However, there are many parts of the world in which Western conceptions of democracy and human rights have not taken root. Instead of simply asserting the inherent superiority of those conceptions in the abstract, it would be more constructive to examine the reasons for this failure in regions that might be more receptive to their own equivalent or corresponding concepts.

Individual civil and political rights are integral to fundamental human rights, as are economic and social rights and collective rights to development and self-determination. Support for this holistic and interdependent concept of human rights includes efforts to promote their legitimacy in all cultures of the world as well as the need to protest their violation by exerting pressure on offending governments to respect them.

The present dynamics of the international protection of human rights operates primarily through the monitoring by Northern organisations of violations in the South in order to lobby Northern governments to pressure Southern governments to respect the human rights of their own populations. A truly universalist dynamic of protection would rely on monitoring and advocacy by local constituencies within the South, such as those that exist in the North, as well as in both directions across the North-South divide. I am not suggesting the abandonment of international monitoring and advocacy as we know it today, but rather seeking to enhance its genuinely global nature by multiplying and diversifying its centres and axes through rooting and legitimating it in the cultures and experiences of all peoples.

Given general agreement that freedom of expression can be limited, by law, to protect the rights of others, we must then ask, which rights, when and how? Who is to articulate and enforce such limits, to what end and on what basis? Since I purport to present an ‘Islamic’ perspective, the basis and nature of claims of Islamicity is the key to the present discussion. Not only do such claims determine the conceptual framework which informs and conditions responses to the sort of questions raised here, they are the criteria by which others, whether insiders or outsiders, can understand and evaluate the substance, content and implications of the claim.

Religion is not excluded from the ambivalence and contestability that characterise all cultures. Even when a religion is, like Islam, believed to be founded on divine scripture and the traditions of the Prophet and other significant communities or personalities, the human interpretation of those sources remains significant. Given unavoidable differences in interpretation of textual sources in historical context, what the religion is believed to be at any given point in time, or to say on any specific matter, is the product of competing human perceptions and prevailing socio-economic factors and forces that have become the prevailing view.

To believers, Islam is primarily and essentially defined by the Quran and Sunna of the Prophet, but, historically, the interpretation and application of these has always been conditioned by the understanding of the Muslim community at any given time or place. While the traditions of early Muslim communities are believed to be authoritative, those who subsequently seek to invoke this authority are themselves similarly conditioned. What Islam means or says on any given matter is therefore what the Muslims of the time and place believe it to be. There is no other way for any religion, to have relevance to the lives of believers.

Senegal: the rommwnty will decide

The dominance of a particular theological interpretation at any time is determined by a variety of factors. Historians may debate the relevance or relative significance of one factor or another, or speculate about the possibility of alternative results given a different set of factors, but the existence and nature of the process itself is beyond dispute.

During the second and third centuries of Islamic history, for example, there was a major debate between the so-called textualists and rationalists (Ash’ariya and Mu’tazila) on some fundamental issues of theology and politics which ended with the dominance of the former and suppression of the latter. One may debate why one view prevailed, or what might have happened under different circumstances, but the facts of the debate and its outcome are accepted by all historians of Islam. It is also clear that, although the Mu’tazila may not subsequently have won the day, elements of their approach and thought have survived and continue to be reflected in internal Muslim debates to the present day.

Whichever group or position a modern Muslim may support in that debate, the need to protect the freedom of expression which allows this sort of debate to take place cannot be denied. The same is true for any set of competing views in the past, present or future of Islamic experience. It is equally true that the winning side would want to curtail the freedom of expression of its opponents in the name of protecting and preserving the integrity of tradition and the stability of religious doctrine.

But since it is the totality of the community of Muslims of the time and place who have the legitimate right to decide which conception of the tradition is to be protected and preserved, and which religious doctrine should be maintained, freedom of expression remains of paramount importance. This conclusion does not yield definitive answers to the questions above — who is to articulate and enforce its limits, to what end and on what basis — but it does provide a clear presumption and orientation in favour of wider freedom of expression, and generally indicates by whom and how limitations may be set in practice.

This may sound exactly like a liberal justification of freedom of expression, but that does not make it necessarily non-Islamic. It is fully and coherently Islamic by virtue of its frame of reference, theological rationale and historical substantiation. This is perhaps the sort of overlapping consensus suggested by Jacques Maritain in a 1949 UNESCO study on the bases of an International Bill of Human Rights whereby different cultures come to a common understanding of the concept and its content, despite their disagreement on its justification.

The issue is not whether Islamic cultures, or any other cultures, are either inherently restrictive or tolerant of relatively greater freedom of expression. Such orientations tend to change over time. Neither is it a matter of citing textual sources or historical experiences as ‘evidence’ of greater or lesser ‘Islamic’ restriction or tolerance since texts are open to competing interpretations and historical experiences are susceptible to shifting characterisations. Reading the Quran and Sunna, one will find authority for liberalism as well as conservatism, and Muslim history gives clear examples of both tendencies. The matter is determined by the choices Muslims make, and the struggle they wage in favour of their choices, in their own historical context.

Secularism came to the Islamic world in the suspect co...